It would seem intuitive that screening for melanoma in at-risk pediatric patients would be worthwhile. And, this has been recommended in pediatric patients with inflammatory bowel disease who have received medications which increase the risk. However, a recent article (HG Welch et al. NEJM 2021; 384: 72-79. The Rapid Rise in Cutaneous Melanoma Diagnoses) provides a lot of reason to question this practice;. This article did not focus on pediatrics but its message about overdiagnosis of melanoma is applicable to this population as well.

Key points:

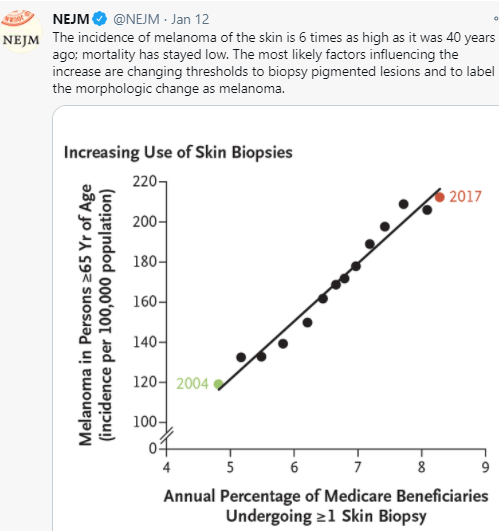

- The increase in melanoma diagnosis (6-fold increase over 40 years) without a significant change in mortality (see Figure 4) indicates that the increase is primarily related to diagnostic scrutiny

- This is driven by a fear of missing a diagnosis, medicolegal concerns and patient anxiety along with lower thresholds for referring to dermatology, lower thresholds for dermatologists to biopsy, and lower threshold by pathologists to diagnose melanoma

- There are “no definitive diagnostic criteria for the pathological diagnosis of melanoma”

- “The incidence of melanoma in situ is now 50 times as high as it was in 1975 (25 vs 0.5 per 100,000 population)…[yet there is a] lack of any appreciable effect in reducing the occurrence of invasive melanoma.”

- Adverse consequences of unnecessary dermatology referrals: feeling vulnerable related to overdiagnosis of melanoma, increased costs, and difficulty obtaining life or health insurance

- More “survivors” of melanoma overdiagnosis increase awareness of melanoma and can increase the cycle of overdiagnosis

My take: Routine visits to dermatology are difficult to justify in the absence of worrisome skin findings. “Although the conventional response has been to recommend regular skin checks, it is far more likely that more skin checks are the cause of the epidemic — not its solution.”