The following except from the New York Times (nyti.ms/1cvUprv ) by Haider Javed Warraich provides some useful advice when families members ask “What would you do if this were your mother?” In pediatrics, the question is similar: “What would you do if this were your child?”

The patient was an elderly woman, admitted to our unit just a few hours earlier, with a breathing machine keeping her alive. We proceeded with the meeting as we were trained to do. We kept our elbows off the table, maintained eye contact (but not too much) and gave the family an update of where we stood.

A healthy family meeting, we’d been told, involved us speaking for about half the time, with the family speaking for the rest – venting, questioning, grieving and hoping, in no particular order. This meeting, though, was dominated by long periods of silence that unearthed the dull, low-pitched drone in the background.

The son, quiet for most of the meeting, broke the silence and, with a hint of anger and a big dollop of frustration, asked the one question I had dreaded being asked the most: “Doc, give it to me straight. If this were your mother, what would you do?”

While the patient-doctor interaction varies widely across cultures and continents, this question seems to be a universal constant…

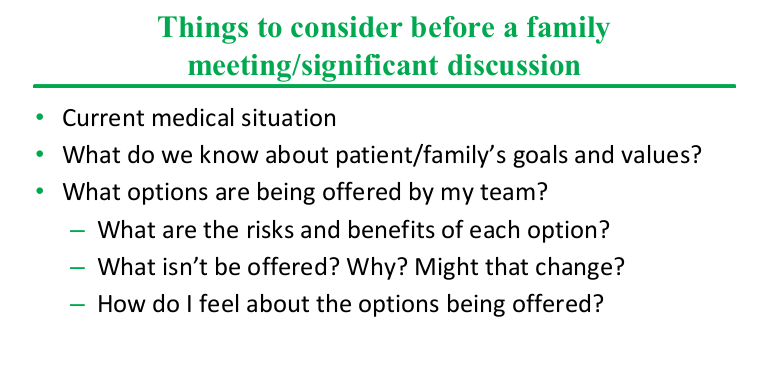

From a patient or family member’s perspective, though, this question helps them make sense of the confusion, desolation and powerlessness that so often defines the hospital experience, which usually involves a full-on assault of numbers, jargon and ‘expert’ opinion. They are confronted with difficult choices, like whether they want to go ahead with a particular high-risk procedure or wait for the tincture of time to kick in…

Yet I still find this question hard to answer. See, my mother is the sort of person who spends two hours each day on the treadmill, even during vacations, so that she can eat to her heart’s content. Often described as a “fighter,” any additional moment she can spend with her children or future grandchildren would be worth the extra mile. My father, on the other hand, is someone who avoids getting his blood sugar level tested to evade medications and dreams of spending his last days in the quiet serenity of the village he grew up in. Thus my answer to the question would be very different, as it would be for anyone, depending on which parent you asked me about.

So I have come to believe that the right answer to the question, “If this were your mother, doctor…” is: “Tell me more about your mother.”

This response gives patients’ families the chance to think about their loved ones, about what they would value and what they would consider a good life, what they would think was worth fighting for if they were available to answer the question for themselves….And then, slowly, the family started sharing stories of the woman we had met only a few hours before, unconscious and intubated. She loved being independent, would hate for people to open doors for her or hold her hand as she tried to get up, they told us. She loved the sun, the beach. She loved walking, loved being out and about. She would never, ever want to go to a nursing home…

We then told them that based on a combination of her vital signs and lab values, as well as our clinical judgment, that while we could hope for some progress, it would likely not be enough to allow her any real shot at experiencing life outside a nursing facility again…

They turned to us and asked us to make her comfortable, and to turn off the breathing machine.

Related blog post:

Advice for doctors after the death of a child | gutsandgrowth