BM Rosenthal et al. NY Times 2/26/25: Organ Transplant System ‘in Chaos’ as Waiting Lists Are Ignored

An excerpt:

The sickest patients are supposed to get priority for lifesaving transplants. But more and more, they are being skipped over…For decades, fairness has been the guiding principle of the American organ transplant system…today, officials regularly ignore the rankings, leapfrogging over hundreds or even thousands of people when they give out kidneys, livers, lungs and hearts…

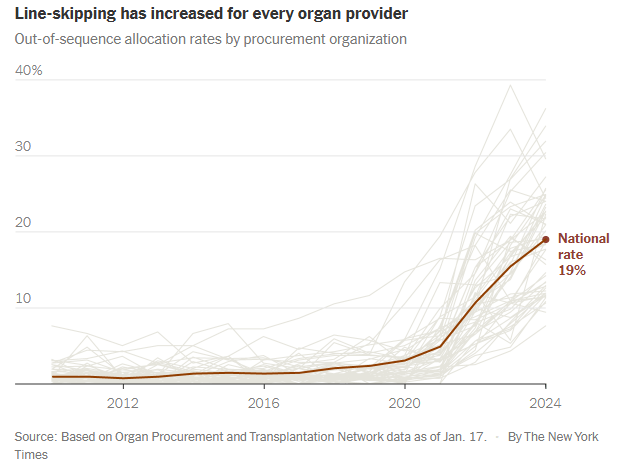

Last year, officials skipped patients on the waiting lists for nearly 20 percent of transplants from deceased donors, six times as often as a few years earlier. It is a profound shift in the transplant system, whose promise of equality has become increasingly warped by expediency and favoritism…

Under government pressure to place more organs, the nonprofit organizations that manage donations are routinely prioritizing ease over fairness. They use shortcuts to steer organs to selected hospitals, which jockey to get better access than their competitors.

These hospitals have extraordinary freedom to decide which of their patients receive transplants, regardless of where they rank on the waiting lists. Some have quietly created separate “hot lists” of preferred candidates...

More than 100,000 people are waiting for an organ in the United States, and their fates rest largely on nonprofits called organ procurement organizations…

The procurement organization is supposed to offer the organ to the doctor for the first patient on the list. But the algorithms can’t necessarily identify exact matches, only possible ones. So doctors often say no, citing reasons like the donor’s age or the size of the organ…

Until recently, organizations nearly always followed the list. On the rare occasion when they went out of order and gave the organ to someone else, the decision was examined by the United Network for Organ Sharing — the federal contractor that oversees the transplant system — and a peer review committee. Ignoring the list was allowed only as a last resort to avoid wasting an organ...

Procurement organizations regularly ignore waiting lists even when distributing higher-quality organs. Last year, 37 percent of the kidneys allocated outside the normal process were scored as above-average…

Skipping patients is exacerbating disparities in health care. When lists are ignored, transplants disproportionately go to white and Asian patients and college graduates…

How a rare shortcut became routine

In 2020, procurement organizations felt under attack. Congress was criticizing them for letting too many organs go to waste. Regulators moved to give each organization a grade and, starting in 2026, fire the lowest performers... the organizations increasingly used a shortcut known as an open offer. Open offers are remarkably efficient — officials choose a hospital and allow it to put the organ into any patient...

Open offers are a boon for favored hospitals, increasing transplants and revenues and shortening waiting times. When hospitals get open offers, they often give organs to patients who are healthier than others needing transplants…Healthier patients are likelier to help transplant centers perform well on one of their most important benchmarks: the percentage of patients who survive a year after surgery...

It is impossible to gauge whether line-skipping prevents wasted organs. But data suggests it does not. As use of the practice has soared, the rate of organs being discarded is also increasing.

My take: This article was eye-opening for me as I am not actively involved in listing patients for transplantation. I was unaware of this increasing tendency of line-skipping and open source allocation. It is disturbing to see the distribution process undermined in this manner –better oversight is needed to assure fairness for those whose lives are at stake.

Related blog posts:

- How to Lower Pediatric Liver Transplantation Waitlist Mortality

- Unfortunate or Unfair Disparities in Liver Transplantation

- Liver Transplant Recipients Are Getting Older | gutsandgrowth

- Picking winners and losers with liver transplantation allocation

- Online Aspen Webinar (Part 7) -Liver Organ Allocation

- What Can Go Wrong with Living Liver Transplantation for the Donor

- Projected 20-Year and 30-Year Survival Rates for Pediatric Liver Transplant Recipients (U.S.)

- Costs and Opportunity Costs in Pediatric Liver Transplantation

- More on Time to Split (2018)

- Need Liver, Will Travel | gutsandgrowth

- Should Younger Transplant Patients Receive Better Organs? | gutsandgrowth