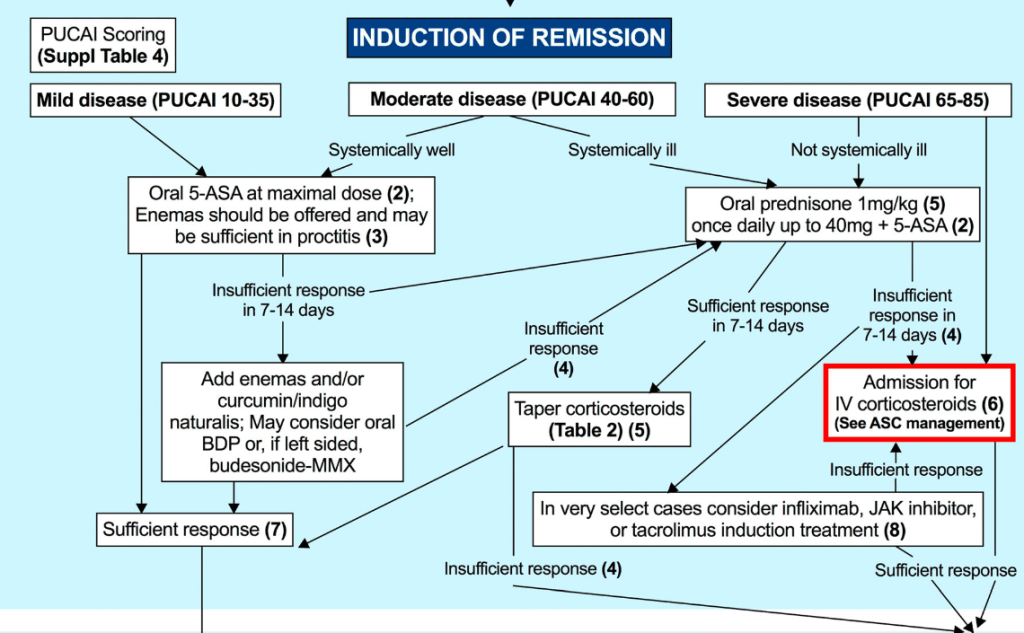

E Wine et al. JPGN 2025;81:765–815. Open Access! Management of paediatric ulcerative colitis, part 1: Ambulatory care—An updated evidence-based consensus guideline from the European Society of Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition and the European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation

This is the first of two highly-detailed papers. (This is a 50 page report.) it has extensive/comprehensive recommendations and information on all aspects of UC management, except acute severe colitis which is covered tomorrow.

Here are some of the recommendations:

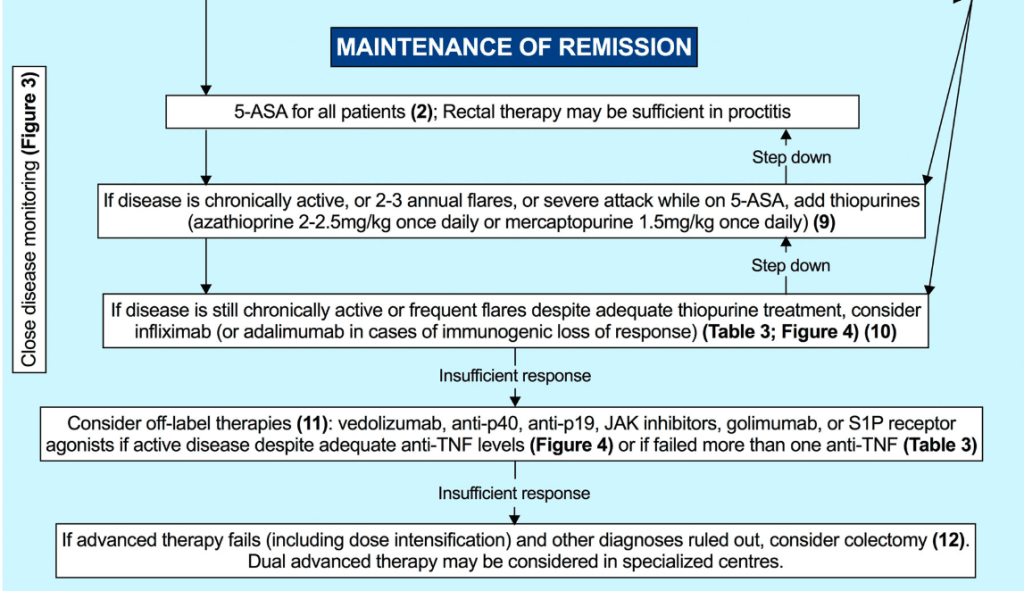

- Thiopurines are recommended for maintaining remission in children who, despite optimal 5-ASA treatment, are corticosteroid-dependent or have frequent relapses (≥2 relapses per year) or in 5-ASA-intolerant patients; thiopurines should be considered following discharge from ASC episodes (EL4, adults EL3) (Agreement 100%).

- Infliximab should be considered, preferably in combination with an IMM, as the first-line biologic agent in chronically active or corticosteroid-dependent UC, uncontrolled by 5-ASA, and in most cases also thiopurines, for both induction and maintenance of remission [EL1, adults EL1] (Agreement 96%).

It is worth noting that anti-TNF monotherapy with pTDM is common practice in the U.S. due to concerns about the safety of combined therapy with a thiopurine (Related blog post: Can Therapeutic Drug Monitoring with Monotherapy Achieve Similar Results to Combination IBD Therapy?). These pediatric guidelines with regard to combination therapy are similar to recent ACG guidelines for adults (D Rubin et al. The American Journal of Gastroenterology 120(6):p 1187-1224, June 2025. Open Access! ACG Clinical Guideline Update: Ulcerative Colitis in Adults).

- Infliximab is recommended to be used preferably in combination with an IMM (with the most evidence in UC being for thiopurines) to reduce the likelihood of developing antibodies to infliximab (ATIs) and in thiopurine-naïve patients, to enhance effectiveness. Methotrexate may also be used to mitigate ATIs. For immunogenicity prevention, lower doses of azathioprine (1–1.5 mg/kg) may be used. Data on methotrexate dose in this setting are scarce, but low total doses of 7.5–12.5 mg weekly are reported. Proactive TDM is recommended, particularly when infliximab is prescribed as monotherapy (Agreement 96%).

- In most cases, higher doses of infliximab (e.g., 10 mg/kg/dose at Weeks 0, 2 and 6, followed by 10 mg/kg every 4–8 weeks for maintenance) are required to provide the best chance of reaching the desired clinical and endoscopic outcome. The dose can be subsequently reduced, guided by TDM. Lower dosing (5 mg/kg) can be used in less severe cases. In cases in which IV infliximab treatment is switched to subcutaneous injections, the recommended dosing schedule (established only for >40 kg) is 120 mg every 2 weeks. See Table 2 for dosing details (Agreement 100%).

- Proactive TDM is recommended for both infliximab and adalimumab, particularly at the end of induction (before the 4th infliximab infusion and after 3 adalimumab injections) [EL4] (Agreement 100%).

Cancer Surveillance:

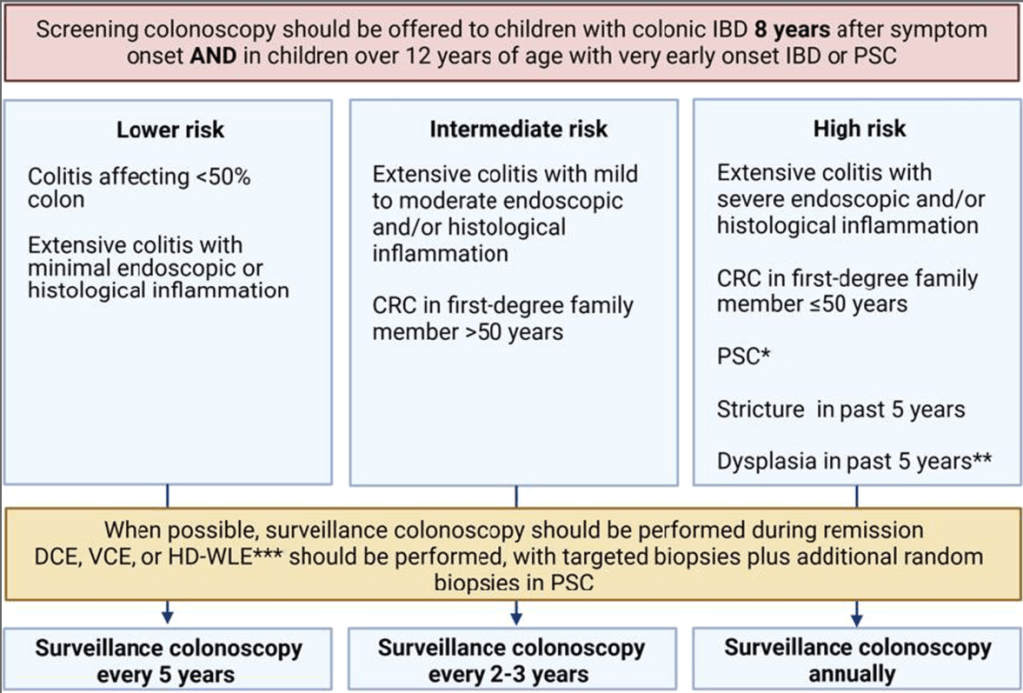

- 1. Children with UC aged 12 years and over with a disease duration of greater than 8 years should be considered for surveillance for CRC and dysplasia [EL4, Adults EL1] (Agreement 96%).

- 2. Children with UC and PSC should be considered for surveillance for CRC and dysplasia starting at age 12, regardless of disease duration [EL4, Adults EL3] (Agreement 100%).

My take: The referenced paper in today’s post and tomorrow’s are essentially updated published book chapters with specific management recommendations. There are likely some practice variations but overall the recommendations will help garner support for current practices like optimizing infliximab dosing and using proactive TDM.

Related blog posts:

- Comparative Evidence and Positioning Advance Therapies for Inflammatory Bowel Disease)

- AGA Living Guideline for Moderate-to-Severe Ulcerative Colitis –The Good and The Bad

- Dr. Joel Rosh: Positioning Therapies for Pediatric Ulcerative Colitis (2024)

- Impressive Results for Risankizumab in Refractory Crohn’s Disease (2024)

- Vedolizumab vs Adalimumab: Histology Outcomes from Varsity Trial, Vedolizumab More Effective Than Adalimumab for Ulcerative Colitis

- IBD Updates: Preventing Inflammatory Bowel Disease with a Healthy Diet and Medication Safety Pyramid

- ARCH Study: Higher Doses of Infliximab in Acute Severe Ulcerative Colitis

- Landmark Study: Oral Biologic for Crohn’s –Upadacitinib

- CCFA 2023 (Atlanta) -Part 1

- CCFA 2023 (Atlanta) Part 4

Disclaimer: This blog, gutsandgrowth, assumes no responsibility for any use or operation of any method, product, instruction, concept or idea contained in the material herein or for any injury or damage to persons or property (whether products liability, negligence or otherwise) resulting from such use or operation. These blog posts are for educational purposes only. Specific dosing of medications (along with potential adverse effects) should be confirmed by prescribing physician. Because of rapid advances in the medical sciences, the gutsandgrowth blog cautions that independent verification should be made of diagnosis and drug dosages. The reader is solely responsible for the conduct of any suggested test or procedure. This content is not a substitute for medical advice, diagnosis or treatment provided by a qualified healthcare provider. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a condition