TA Brenner et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2026: 24: 7-9. Geodemographic Trends in Private Equity Acquisitions of US Gastroenterology Practices: An Analysis of Transactions From 2013 to 2023

An excerpt:

“The combination of high-volume procedures, strong ancillary revenue streams, and opportunities for outpatient consolidation has made gastroenterology a prime target for PE-backed investment. For many gastroenterologists, this trend is no longer theoretical—it is local, visible, and shaping the landscape of everyday practice.”

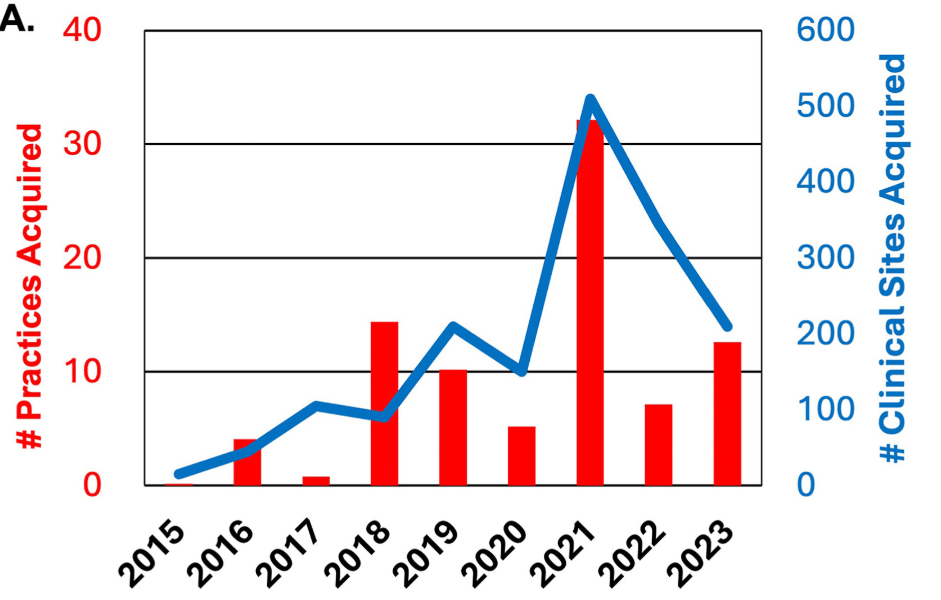

“Between 2013 and 2023, PE firms acquired 114 outpatient gastroenterology practices, encompassing 1169 clinical sites nationwide…That includes 854 clinics, 266 endoscopy centers, and 49 infusion centers. Collectively, these sites employed approximately 2675 physicians and advanced practice providers. In total, around 14% of all gastroenterology clinical sites nationwide are now affiliated with PE-backed platforms.”

and gastroenterology clinical sites (blue) by year.

“PE firms are less likely to invest in gastroenterology practices located in the poorest communities… Practices in zip codes with the lowest income levels were about 60% less likely to be acquired than those in wealthier areas (aRR, 0.37; 95% CI, 0.31–0.45; P < .001)…PE firms tend to prioritize markets with strong commercial payer mixes and higher rates of elective procedures, steering clear of areas with high Medicaid penetration or large numbers of uninsured patients.”

Key Points:

- “First, consolidation is accelerating…Even if you are not interested in selling, you may need to compete with PE-backed groups that have more capital, better tech infrastructure, and stronger payer contracts”

- “Second, staying independent may become more difficult. As regional consolidation increases, remaining unaffiliated could put independent practices at a disadvantage. PE-backed platforms often negotiate better rates with commercial insurers and have the scale to invest in centralized billing, marketing, and compliance.”

- “Third…If PE firms avoid lower-income or rural areas, gastroenterology access could become more uneven and more challenging to sustain in underserved regions.”

- “Studies in other specialties suggest that practices owned by PE firms often face changes in staffing, autonomy, and productivity expectations. Physicians may experience higher pressure to perform more procedures, see more patients, or adopt system-wide workflows they did not design.”

My take: PE acquisitions are affecting broad areas of healthcare. However, they do not seem to result in improvement in patient care or physician satisfaction.

Related blog posts:

- Complications After Private Equity Takeover

- Private Equity in Gastroenterology & More Broadly

- Case Study of Private Equity in Physician Practices: Anesthesia in Colorado

- Why Corporatization Occurs in Health Care

- Unpacking Health Care Corporatization in the U.S.

- The Failing U.S. Health System

- I Call BS -Consolidation in GI is Not a Good Trend

- What Is Driving Hospitals’ Acqui$ition of Physician Practices?