E Walsh et al. Am J Gastroenterol 2024; 119: 2198-2205. Laryngeal Recalibration Therapy Improves Laryngopharyngeal Symptoms in Patients With Suspected Laryngopharyngeal Reflux Disease (Thanks to Ben Gold for this reference)

For a lot of patients with rheumatologic complaints like joint pain, treatment often consists of sending patients to physical therapy rather than using pharmaceuticals. This type of approach is under-utilized in gastroenterology. A recent study, however, suggests that an analogous approach is likely beneficial in patients with chronic laryngopharyngeal symptoms.

Background: Laryngopharyngeal symptoms such as cough, throat clearing, voice change, paradoxic vocal fold movement, or laryngospasm are hyper-responsive behaviors resulting from local irritation (e.g., refluxate) and heightened sympathetic tone. Laryngeal recalibration therapy (LRT) guided by a speech-language pathologist (SLP) provides mechanical desensitization and cognitive recalibration to suppress hyper-responsive laryngeal patterns.

Methods: Adults (n=65, mean age 55 years) with chronic laryngopharyngeal symptoms referred for evaluation of GERD to a single center were prospectively followed. Inclusion criteria included ≥2 SLP-directed LRT sessions (60 minutes sessions). “Mechanical desensitization focuses on well-known laryngeal suppression techniques (i.e. pursed lip breathing to suppress throat clearing or cough) or changing voice production by means of acoustic and aerodynamic techniques…Cognitive recalibration uses relaxation and conceptualization of symptoms to rework thought patterns around chronic laryngeal behaviors.”

Key findings:

- Overall, 55 participants (85%) met criteria for symptom response. 17 (26%) had complete resolution, 19 (29%) had near-complete resolution, and 19 (29%) had a moderate response

- Specifically, symptom response was similar between those with isolated laryngopharyngeal symptoms (13/15, 87%) and concomitant laryngopharyngeal/esophageal symptoms (42/50, 84%)

My take: Historically, patients with laryngopharyngeal symptoms have been difficult to treat. Many do not respond to reflux therapies. This study highlights a different approach and shows that the benefit of working with highly-skilled SLPs.

Related blog posts:

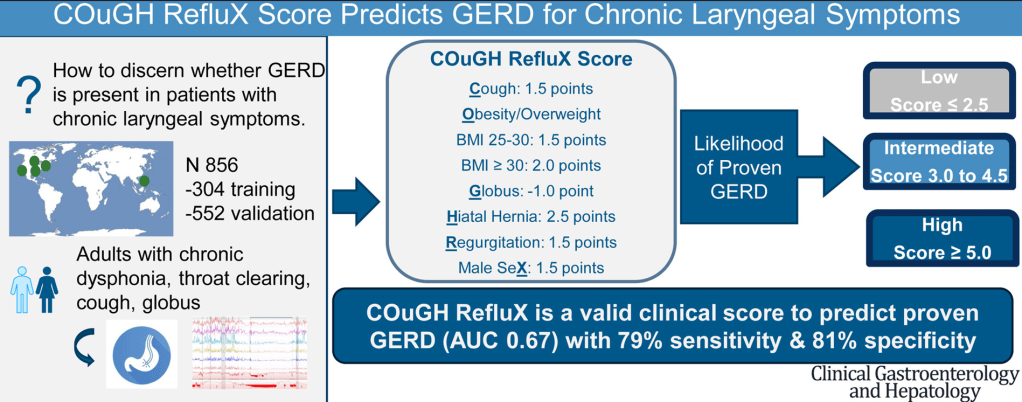

- How to Sort Out Chronic Laryngeal Symptoms and Reflux

- Current Thinking with Laryngopharyngeal Reflux Symptoms

- Understanding Reflux/Airway Disease and Potential Role of Airway Impedance

- Better to Do a Coin Toss than an ENT Examination to Determine Reflux

- Clinical Practice Update: Extraesophageal Symptoms Attribute to Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease

- Gastroesophageal Reflux Phenotypes and “Where Rome, Lyon, and Montreal Meet”

- Accuracy of ENT diagnosis of Reflux Changes

- Incredible Review of GERD, BRUE, Aspiration, and Gastroparesis