O Ackermann et al. Gastroenterol 2026; 170: 188-198. The Natural History of Gastroesophageal Varices in Children With Portal Hypertension

Methods: Retrospective review of 1586 children with portal hypertension. 590 had two or more upper endoscopies (403 with biliary atresia).

“For the purpose of this study, and based on our previous experience in children,8,11 the endoscopic pattern associated with a high risk of bleeding (ie., HRV) included grade 3 esophageal varices as well as grade 2 esophageal varices with red color signs or gastric varices (cardia), or both.”

The authors developed a HRV [high risk of varices] score as a composite index calculated as follows: 1 point for grade 1 esophageal varices, 2 points for grade 2 varices, 3 points for grade 3 varices, and 1 point each for the presence of red color signs or GOV1 (HRV score range, 0–5). High-risk varices had an HRV score of 3 to 5.

Key findings:

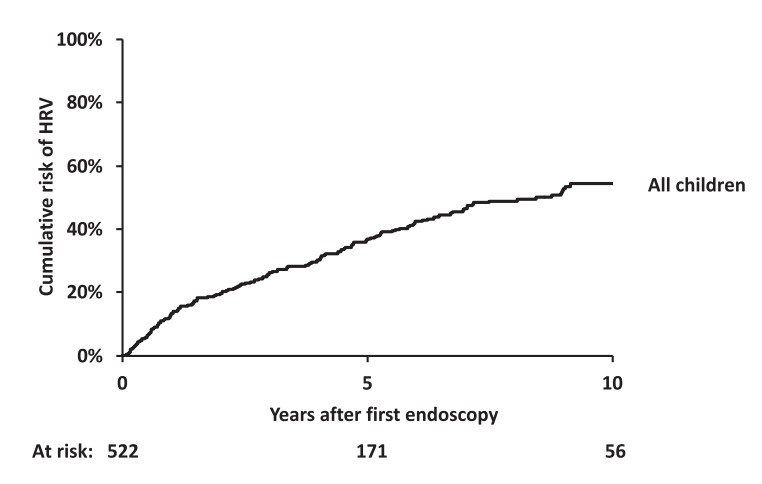

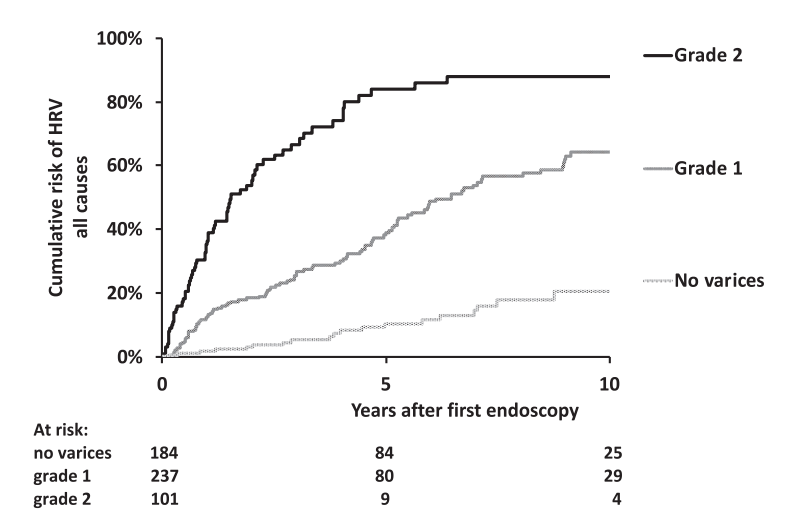

- Worsening of the endoscopic pattern occurred in 58% of children over a mean 4-year interval

- 5- and 10-year probabilities of HRV emergence in initially HRV-negative children were 36% and 54%, respectively

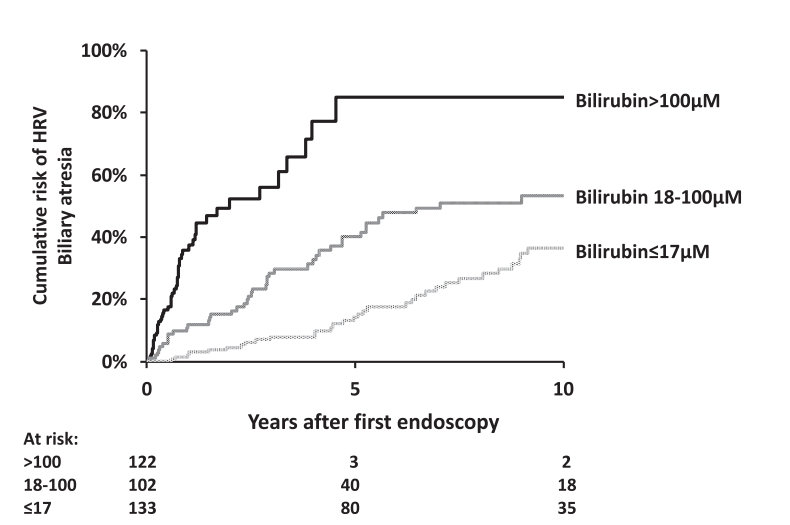

- Infants with biliary atresia are at particularly high risk with correlation to the degree of cholestasis (see below)

- Platelet count less than 150,000 as an indicator of HRV was mainly useful in older children. “A platelet count of ≥150,000/mm3 was recorded in 205 of the 629 children (32%) with HRV. Moreover, there was a decrease with age in the proportion of children with HRV and a platelet count of ≥150,000/mm3, falling from 62% in children aged <12 months to 2% in patients aged >10 year.” 16% of children 6-8 yrs, 12% of children 8-10 years of age with HRV had platelet count ≥150,000/mm3

- “Gastrointestinal bleeding was recorded in 36 of 947 children (3.8%) who did not have HRV at their last endoscopy and in 270 of the 359 children (75%) with HRV at their last endoscopy who did not undergo endoscopic or surgical primary prophylaxis of bleeding.”

Discussion Points:

- Variceal progression was much faster in infants and is is likely due to the severity of cholestasis and its impact on portal hypertension.

- “It is notable that children with Alagille syndrome and those with genetic cholestasis with normal GGT have a lower rate of variceal progression and a lower mean HRV score than children with biliary atresia, despite comparably high levels of bilirubin. This suggests that different mechanisms of cholestasis … may have distinct consequences on intrahepatic portal vein branches resulting in varying degrees of portal hypertension.”

- “In children with biliary atresia aged <12 months, grade 2 esophageal varices without red color signs or GOV1 (HRV score of 2) should be considered an indication for endoscopic primary prophylaxis.”

- “Because the efficacy and safety of β-blockers have not been established in children, we suggest that this pattern—grade 1 varices with red color signs or GOV1—should prompt early repeat endoscopy to detect HRV in a timely manner…this repeat endoscopy could be recommended 6 months after the previous one.”

- Limitations: High proportion of children with biliary atresia (limits conclusions with other disorders), and retrospective study since 1990

- “Pending the results of future studies, the detection of palpable splenomegaly remains a simple and practical criterion for initiating screening endoscopy in children with portal hypertension”

My take: This is a very useful study providing important data to help improve decision-making in children with portal hypertension.

Related blog posts:

- Selecting Patients with Biliary Atresia for Variceal Endoscopy Screening

- “White Nipple Sign” (aka Mount St. Helens’ sign) and Varices

Time to Adjust the Knowledge Doubling Curve in Hepatology (2021) The 2nd guidance in this review discusses procedures for bleeding in patients with chronic liver disease. - New Paradigm in Treating Varices and Cirrhosis Management (in Adults)

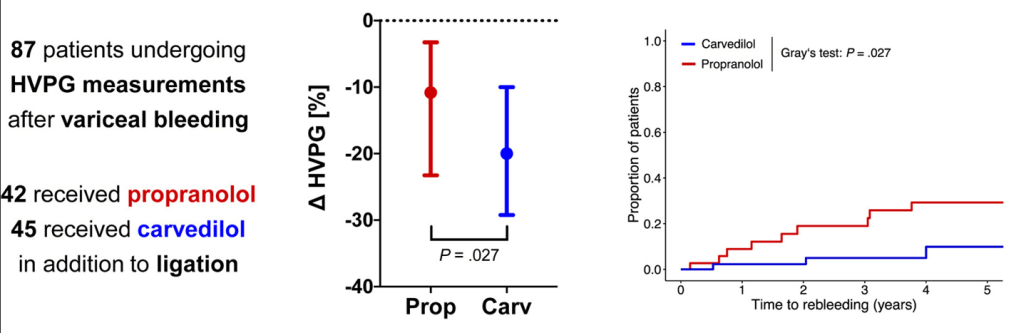

- Why Carvedilol Is Considered Best Pharmaceutical Agent to Prevent Variceal Bleeding (in Adults)

Disclaimer: This blog, gutsandgrowth, assumes no responsibility for any use or operation of any method, product, instruction, concept or idea contained in the material herein or for any injury or damage to persons or property (whether products liability, negligence or otherwise) resulting from such use or operation. These blog posts are for educational purposes only. Specific dosing of medications (along with potential adverse effects) should be confirmed by prescribing physician. Because of rapid advances in the medical sciences, the gutsandgrowth blog cautions that independent verification should be made of diagnosis and drug dosages. The reader is solely responsible for the conduct of any suggested test or procedure. This content is not a substitute for medical advice, diagnosis or treatment provided by a qualified healthcare provider. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a condition.