J Huang et al. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2025;81:1488–1495. Open Access! Numbers matter: How pediatric endoscopy quality varies with annual procedural volume

In this retrospective study with 985 ileocolonoscopies (2021-2024):

Methods: “Quality indicators were compared across groups using Kruskal–Wallis analyses. Multivariate modeling was performed to identify variables predicting terminal ileal intubation and TIIR ≥ 85%.”

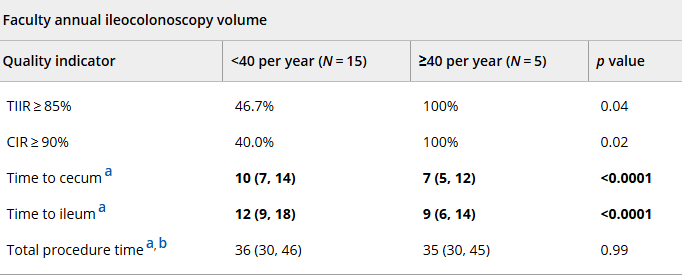

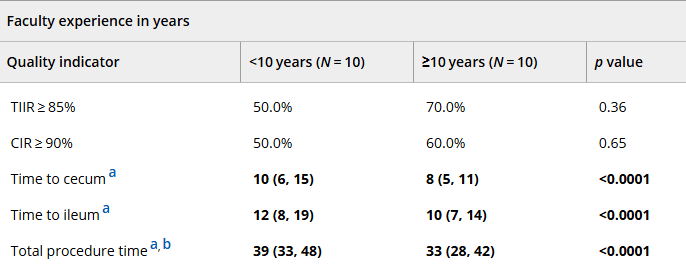

Key findings:

- Overall ileal intubation rate (TIIR) and cecal intubation rate (CIR) were 86.3% and 91.6%, respectively

- Annual procedure volume ( APV ≥ 40) was identified as predictive for TIIR ≥ 85% (p < 0.01)

- Faculty years’ experience (≥10 vs. <10 years) predicted shorter procedure duration (adjusted hazard ratio [confidence interval]: 1.40)

- Adequate bowel prep was associated with higher TIIR (901% vs 76.7%), CIR (93.8% vs 86.0%) and shorter duration procedures (34 min vs 41 min)

Bolded text and numbers reflect results demonstrating statistical significance

My take (borrowed in part from the authors): The authors state that “our findings suggest that a threshold of 40 annual procedures [ileocolonoscopies] is necessary to maintain high pediatric endoscopic quality.” While I agree that adequate procedural volume is helpful, there is a great deal of individual variation/ability. Particularly if the endoscopist has a lower procedural volume, metrics like ileal intubation rate can be useful to assure good quality.

Related blog posts:

- Our Study: Provider Level Variability in Colonoscopy Yield

- How Much Harder is a Colonoscopy in Children Less Than 6 Years of Age

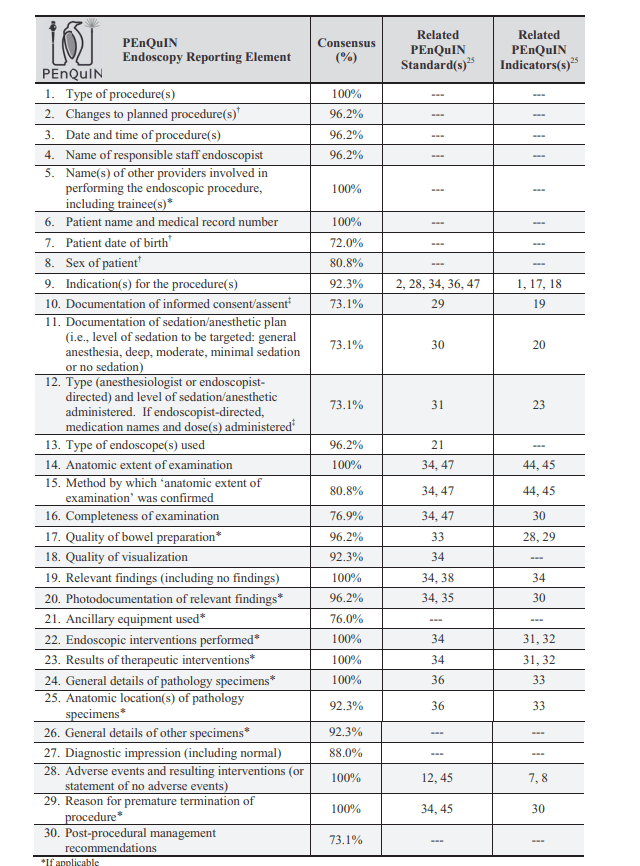

- PEnQuIN and Improving the Quality of Pediatric Endoscopy

- Improving the Value of Pediatric Colonoscopy

- Isolated Ileitis in Children

- Diagnostic Strategy For Children with Diarrhea and Abdominal Pain

- #NASPGHAN19 Postgraduate Course (part 3)

- Colonoscopy and Isolated Abdominal Pain = Low Value Care

- Quality Metrics in Pediatric Colonoscopy