- F Tian et al. Hepatology 2024; 80: 440-450. Open Access! Feasibility of hepatitis C elimination by screening and treatment alone in high-income countries

- L Kondili, A Craxi. Hepatology 2024; 80: 263-265. (editorial) Open Access! Hepatitis C elimination: Tailoring the approach to each country’s needs and realities

Methods: The authors developed an agent-based model (ABM) “simulating the dynamics of HCV transmission and demographic changes from 2006 to 2030, using data from Ontario, Canada.14 Predicted long-term health outcome effects for current HCV policies (status quo) and those following the implementation of various scale-up interventions were compared to the elimination goals set by the WHO.”

Key findings:

- Under the current status quo of risk-based screening, we predict the incidence of CHC-induced decompensated cirrhosis, HCC, and liver-related deaths would decrease by 79.4%, 76.1%, and 62.1%, respectively, between 2015 and 2030

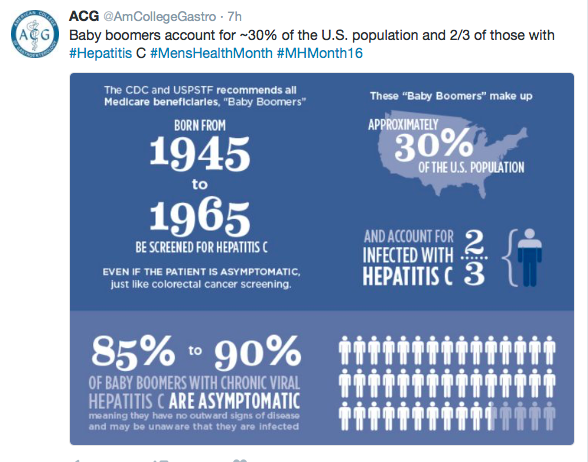

- However, chronic hepatitis C (CHC) incidence would only decrease by 11.1% (WHO goal by 2030 is a reduction of 80%)

From the editorial:

“According to the study by Tian et al,3 the future incidence of HCV infection will be mainly related to HCV transmission, stressing the fact that harm reduction strategies, in addition to the highest treatment rate, are paramount to reducing the further HCV spread and reinfection risk, especially in marginalized populations. In high‐income countries, HCV treatment rates among people who use drugs remain inadequate due to a lack of simplified HCV testing, scale‐up of harm reduction‐based HCV treatment programs, and numerous additional barriers to HCV services.”

“It is not just a matter of time until high-income countries get rid of HCV infection. The ongoing mass screening campaign in Italy shows that having political will and financial coverage is insufficient to achieve the HCV elimination targets. In high-income countries, encouraging and convincing people to get tested is among the most challenging and underrated.”

My take: The development of highly effective HCV treatments has been a remarkable feat, reducing the rate of death and complications from HCV. Nevertheless, it has not brought about a big improvement in HCV transmission. To achieve this, it looks like a vaccine will be necessary. Until then, our fight against HCV is akin to the ‘rope a dope‘ boxing strategy –we are not getting a knock-out anytime soon against this opponent.

Related blog posts:

- The Best Time To Treat Children with Hepatitis C And Cost Considerations

- Year-in-Review for Pediatric Hepatology (2024)

- Hepatitis C Infections Increasing -Tied to Opioid Crisis

- Opioid Epidemic Affecting HCV Infection in Adolescents (as well as adults)

- The Dark Cloud Inside the Silver Lining -What’s Really Going on with Hepatitis C Infection

- Resolution: Eradication of Hepatitis C

- Medical Progress: Toward Hepatitis C Elimination (2020)

- Online Aspen Webinar (Part 4) -How to Treat Hepatitis C in Children (2020)