A shout out to Ben Gold who is a coauthor on several new publications:

A Krasaelap et al. JPGN 2023; 77: 460-467. Pediatric Aerodigestive Medicine: Advancing Collaborative Care for Children With Oropharyngeal Dysphagia

This is a terrific review of the dysphagia and the multidisciplinary approach to management. Many pearls are in this article. For example, laryngo-tracheo-esophageal cleft (LTEC), “while rare, 1 in 10,000-20,000 live births, the incidence of LTEC is higher (7.6%-22%) in children with aerodigestive issues such as a chronic cough.” [As an aside, this should be repeated given the changing population of patients being seen.]

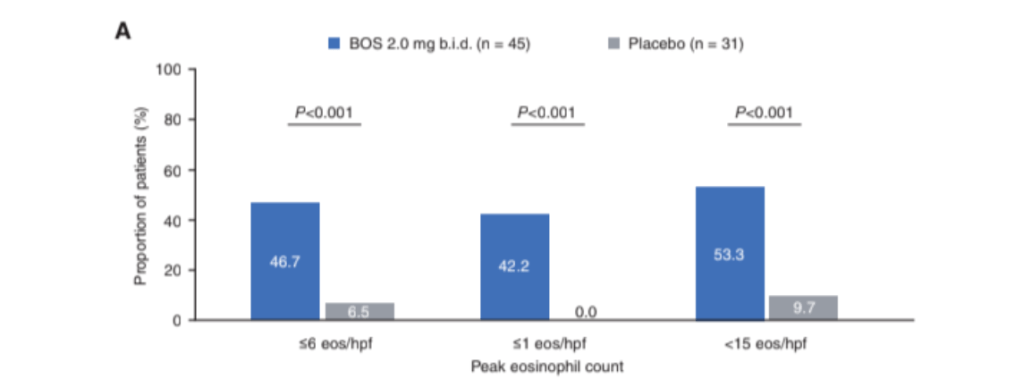

VA Mukkada, SK Gupta, BD Gold et al. JPGN 2023; 77: 760-768. Pooled Phase 2 and 3 Efficacy and Safety Data on Budesonide Oral Suspension in Adolescents with Eosinophilic Esophagitis

Key finding: Significantly more patients who received BOS (2mg BID) than placebo achieved histologic responses (≤6 eos/hpf: 46.7% vs 6.5%; ≤1 eos/hpf: 42.2% vs 0.0%; <15 eos/hpf: 53.3% vs 9.7%; P < 0.001)

Related blog posts:

- Increasing Burden of Eosinophilic Esophagitis

- Long-Term Treatment of Eosinophilic Esophagitis with Budesonide

- Phase 3 Trial of Budesonide for Eosinophilic Esophagitis & COVID-19 Deaths in U.S.

- Head-to-Head: Budesonide vs Fluticasone for Eosinophilic Esophagitis

- Orodispensable Budesonide Tablets for Eosinophilic Esophagitis

- Surprising Findings in Prospective Budesonide-Eosinophilic Esophagitis Study

- Aerodigestive Complexity Score

- What Should an Aerodigestive Program Look Like

- CCFA Premier Physician -Ben Gold, MD