The U.S. government now pays for nearly 50% of health care expenditures (Government Now Pays For Nearly 50 Percent Of Health Care Spending, An Increase Driven By Baby Boomers Shifting Into Medicare, Kaiser Health News, 2/21/19). Both in adults and children, the share of public sector spending is increasing. The biggest areas of costs include Medicare, Medicaid, CHIP and Veterans health care. The U.S. government also funds the HHS which includes the FDA, NIH, CDC, and AHRQ.

A recent commentary (JM Perrin et al. NEJM 2020; 383: 2595-2598. Medicaid and Child Health Equity) describes what is happening with Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP).

Key points:

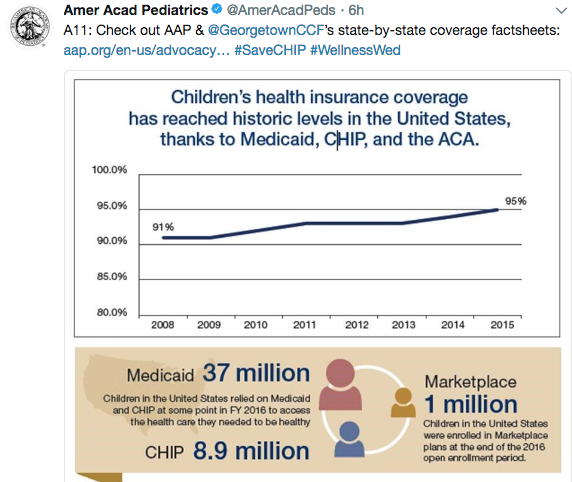

- Over the past 20 years, the proportion of pediatric health care coverage provided by Medicaid and CHIP has been increasing. In 1997, these programs represented about 15% of health care coverage compared to ~35% in 2018. This corresponds to reductions in employer-provided coverage

- Unlike private insurance, Medicaid is always available as it doesn’t have fixed enrollment periods

- Medicaid disproportionately covers minority populations

- State funding of Medicaid creates challenges. “States have routinely used strategies for limiting enrollment”

- “Medicaid’s low physician payment rates, which average about two-thirds of rates paid by Medicare for the same services, depress physician participation…Lack of access to specialists poses additional problems in many communities”

- The authors recommend the following:

- Medicaid should be expanded to cover all children from birth through 21 years of age

- The federal government should assume full financial responsibility

- Medicaid payments should parallel national Medicare standards

Related blog posts:

- “Health Insurance Is Broken”

- NY Times: America can afford a world-class health system. Why don’t we have one?

- We are Last in Health Care Among High Income Countries

- How The IRS Proved That Health Insurance Saves Lives | gutsandgrowth

- Zip code or Genetic code -which is more important? gutsandgrowth

- New study finds 45,000 deaths annually linked to lack of health …

- A Leading Cause of Mortality in U.S…. | gutsandgrowth

- No Exaggeration: Too Many Children Are Dying in the U.S.

- “America’s Huge Health Care Problem”

- Healthcare: Where the Frauds are Legal