Though young age at the time of Kasai and surgical experience have been identified as factors in the long-term outcome of patients with biliary atresia (BA), why is it that some with timely intervention still fail to respond? Conceptually, I’ve considered those who had progressive disease as probably having an intrahepatic component of their biliary disease that a Kasai operation cannot help.

New research (Z Luo, P Shivakumar, R Mourya, S Gutta, JA Bezerra. Gastroenterol 2019; 157: 1138-52) identifies genetic factors that are likely a more powerful predictor of Kasai response then the traditional clinical factors.

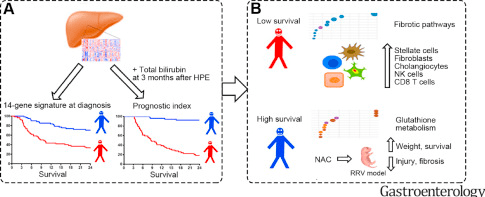

The science in this study is fascinating –combining genetic heat maps, and survival curves. The prediction with a 14-gene signature is amplified with serum total bilirubin at 3 months post-Kasai. In addition, these studies are combined with a mouse model treated with N-acetylcysteine (NAC). Histologic changes were then assessed.

Key findings:

- The 14-gene mRNA expression pattern predicted shorter and longer survival times in both the discovery (n=121) and validation sets (n=50) of children with BA (see figure below: red curve vs blue curve)

- When this 14-gene expression pattern was paired with total bilirubin level 3 months after Kasai, this identified children who survived with their native liver at 24 months with an area under the curve of 0.948 in the discovery set and 0.813 in the validation set (P<.001).

- In those with transplant-free survival, many of the mRNAs expressed had increased scores for glutathione metabolism. Subsequently, mice with BA were treated with NAC (which promotes glutathione metabolism) & had reduced bile duct obstruction, liver fibrosis, and increased survival times.

- In children with lower survival rates, there was increased mRNA expression of proteins encoding fibrosis genes in the liver tissues.

My take: This 14-gene signature has the potential to change our approach to children with BA. Also, when evaluating surgical success rate, these underlying genetic factors will need to be incorporated.

Related blog posts:

- 30 -year outcomes with biliary atresia

- Bad News Bili | gutsandgrowth

- Outcomes of Biliary Atresia | gutsandgrowth

- Outcome of “Successful” Biliary Atresia Patients

- Blood Test is Better Than a Liver Biopsy for Bilary Atresia

- How To Diagnose Biliary Atresia in 48 hrs

- New Way to Diagnosis Biliary Atresia

- Will We Still Need a Liver Biopsy to Diagnose Biliary Atresia in a Few Years?

- Helpful Review on Biliary Atresia | gutsandgrowth

- Biliary Atresia More Common in Preterm Infants