Recently, Dr. Steve Erdman gave our group a great update on polyposis disorders. My notes below may contain errors in transcription and in omission. Along with my notes, I have included many of his slides.

Key points:

- There has been breath-taking progress in understanding of polyposis disorders. It is important to have genetic counselors participate to optimize testing and evaluation

- In patients with suspected polyposis syndromes, a genetic diagnosis is very important and can help guide management

- Family history is very important. If several family members have had GI or other cancers at a young age, more aggressive interventions are usually indicated. However, individual family members can have a wide variation in presentation

- In patients with many polyps, it is worthwhile to alert family to the fact that some polyps can be missed on colonoscopy and to contact medical team if there are recurrent symptoms like rectal bleeding

- Some disorders, like juvenile polyposis syndrome (JPS), the connection between polyp presence and cancer risk is not clear. The increased risk for colon cancer my remain after polypectomy.

- For most individuals with adenomatous polyps, removal of the polyps prevents cancer development (in the GI tract) as there is a well-described adenoma-to-cancer sequence that typically takes 7-10 years to progress from adenoma to colon cancer

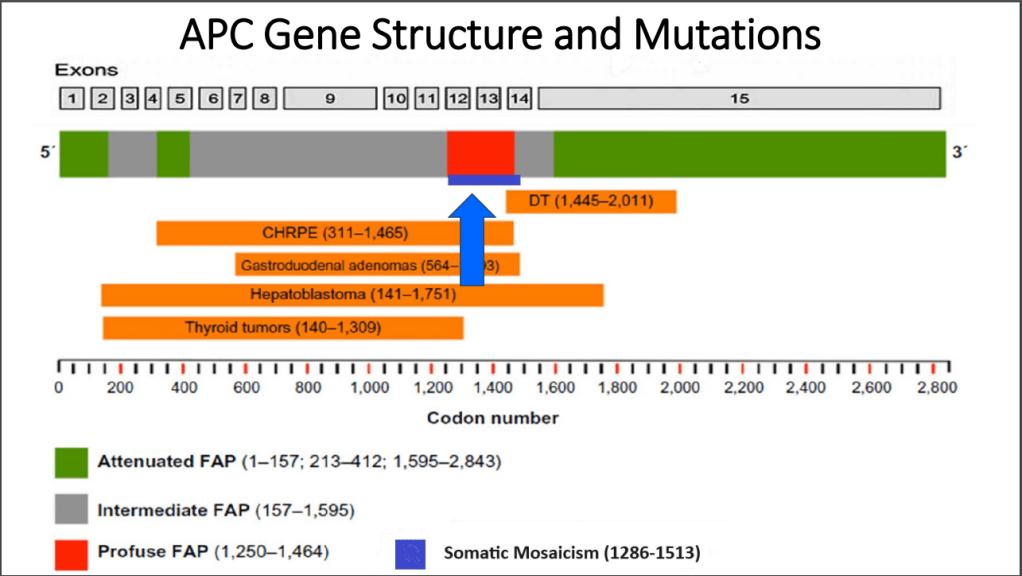

- With FAP, the severity is related in part to the specific mutation. Mutations in the mutation cluster region are associated with an aggressive phenotype and mutations causing attenuated FAP are less aggressive

- For FAP, timing of potential colectomy involves factors including severity as well as social factors. In teenagers in which there is a concern about being lost to follow-up, this is a factor that could influence earlier intervention

- Many times a 2nd opinion in pathology can be helpful, especially if colon cancer is reported. However, histologic dysplasia can be tricky as well

- Isolated CHRPE usually does not require evaluation. Dr. Erdman noted that sometimes genetic testing is offered to a family for reassurance. He discouraged colonoscopy in this setting unless a genetic diagnosis has been established or symptoms like rectal bleeding are present. The penetrance of APC mutations (development of polyps) can be quite variable (especially with attenuated form)

- For JPS, after all polyps have been removed, consider surveillance every 3-5 years or for active symptoms (related post: ESPGHAN Juvenile Polyposis Syndrome in Children –Position Paper)

Case #1 presented a 14 yo with 50+ multilobulated pedunculated polyps which histologically were tubulovillus adenomas. Initial diagnosis was elusive despite extensive testing

Case#2 presented 8 yo twins. Aggressive management was indicated as 5 family members developed colorectal cancer prior to age 20 years.

Case#2 Improvements in testing allowed identification of a point mutation in the 1B promoter region of the APC gene

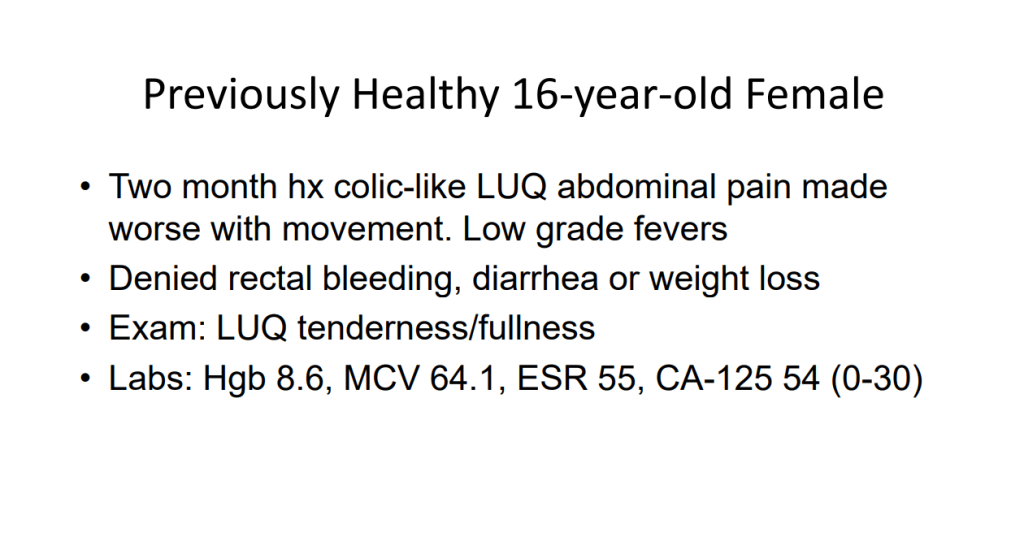

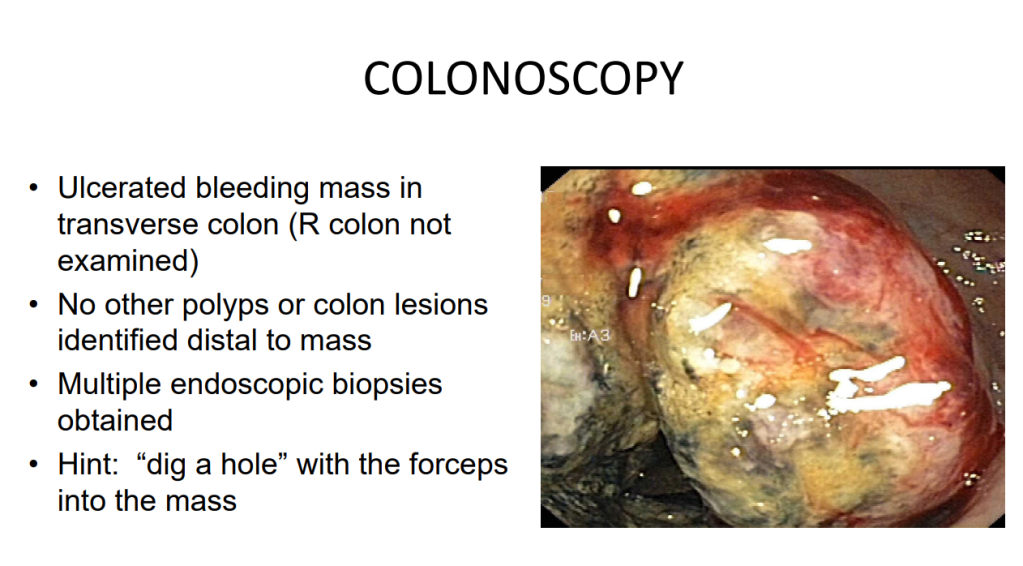

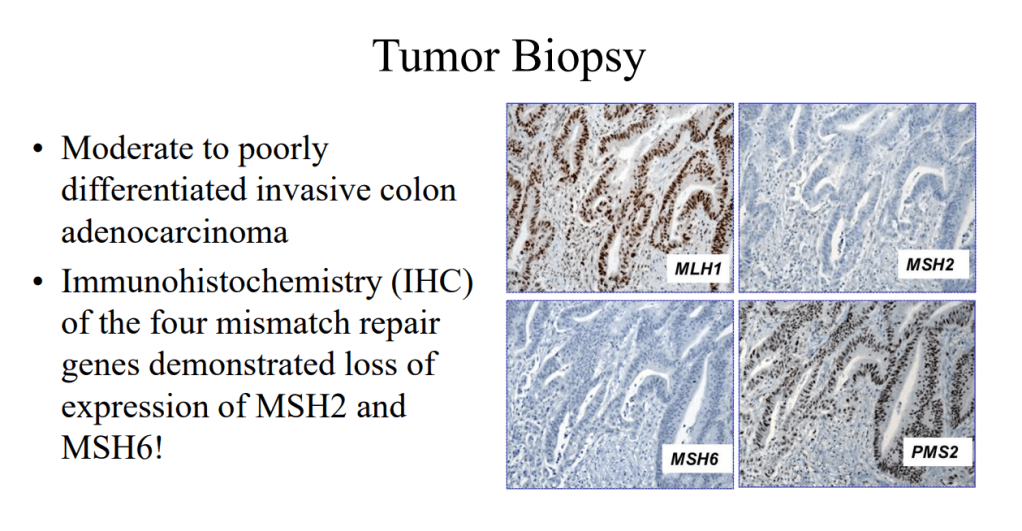

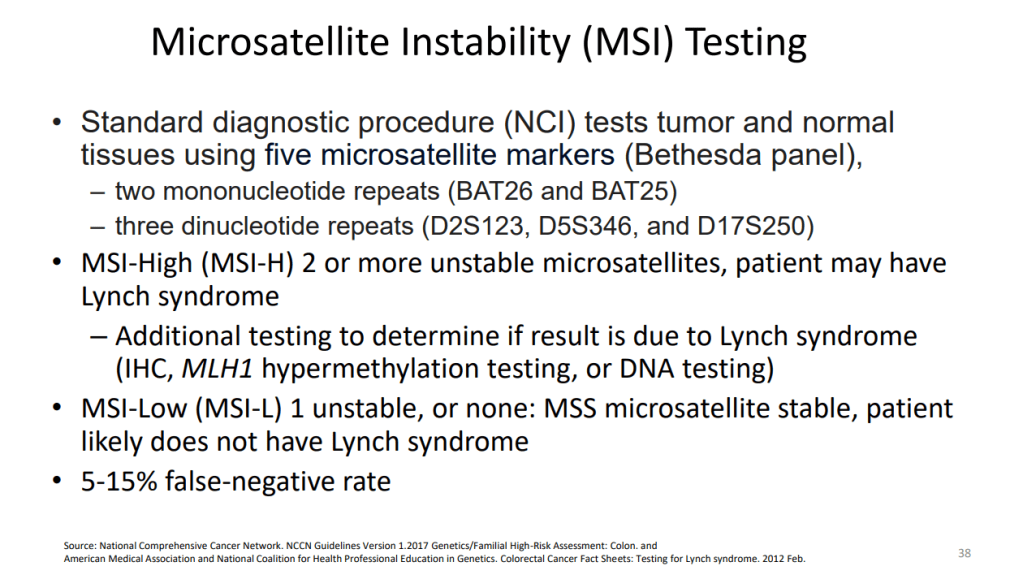

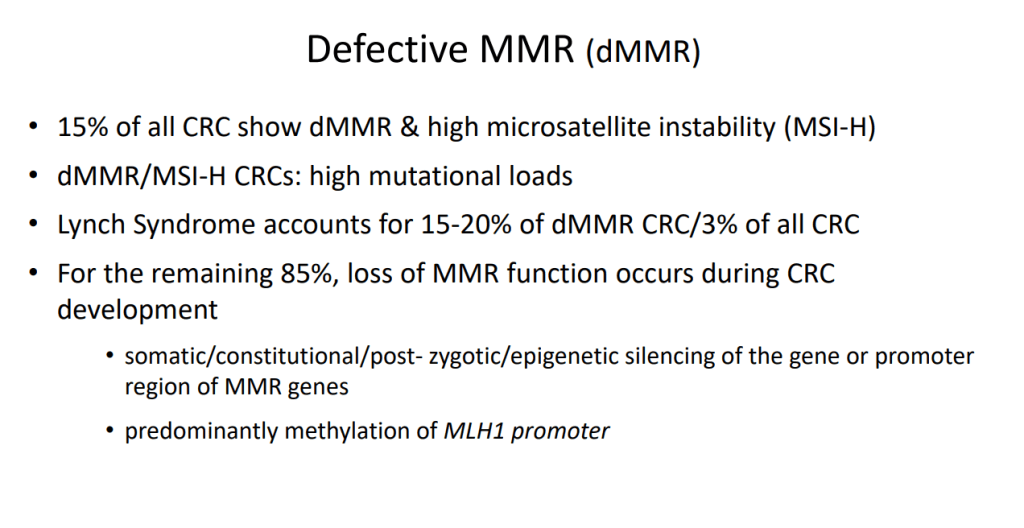

Case#3 presented a 16 yo with anemia and pain who was found to have a colonic mass related to mismatch repair mutation. Dr. Erdman indicated that obtaining adequate tissue for a diagnosis (“dig a hole”) is important. (As an aside, other colleagues have had the experience of tumors which were highly vascular and it is important to keep this possibility in mind)

Case#4 presented a 12 yo with neurofibromatosis (NF-1) who developed CRC and ultimately diagnosed with CMMR-D. This is a highly aggressive cancer susceptibility disorder with a very poor prognosis (see post: Are you familiar with CMMR-D?)

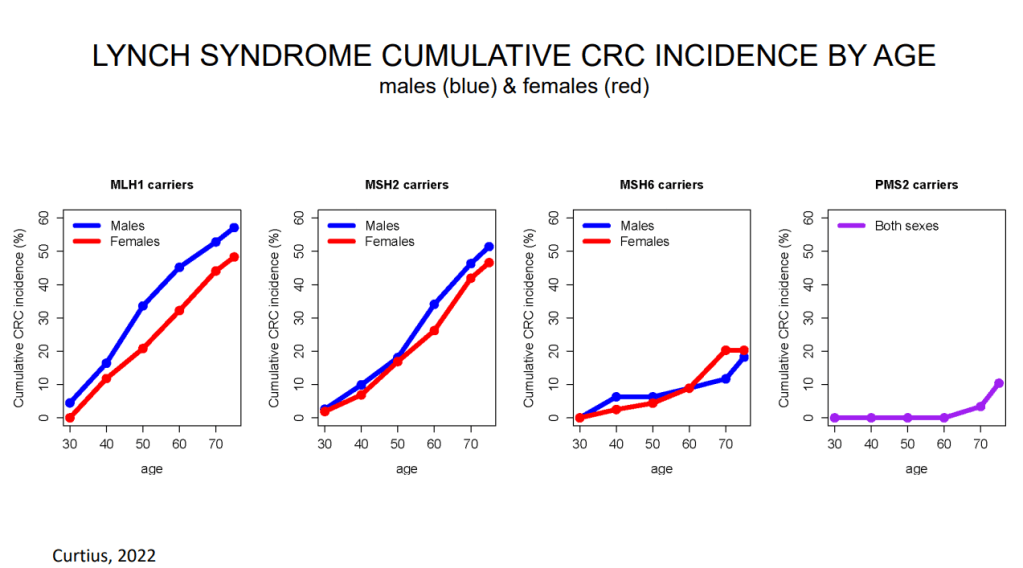

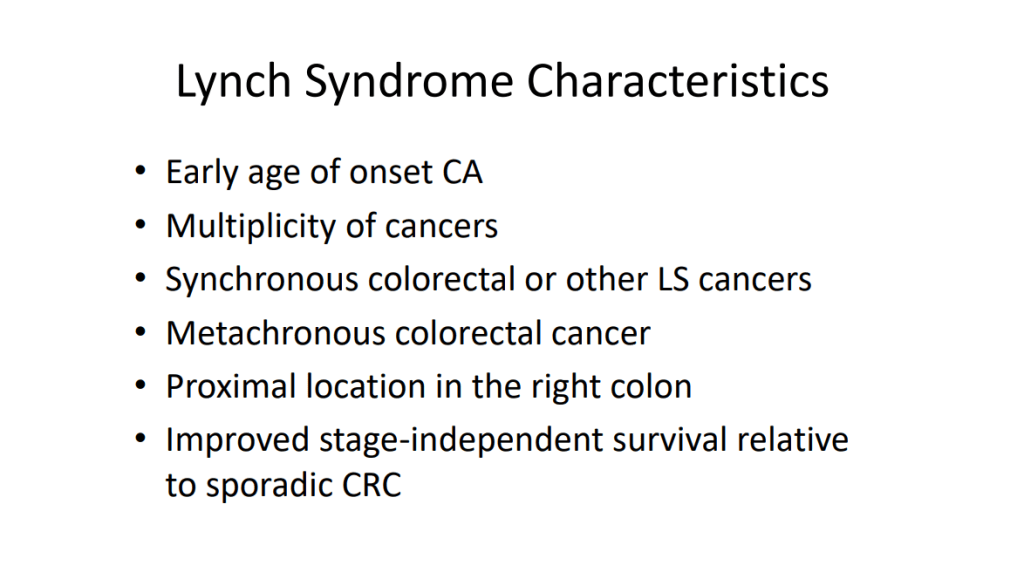

- Case#5 presented two siblings (13 yo, 17 yo) who had half-sibling who died from CRC at age 25 yrs. This case illustrated “genetic anticipation” as each generation in this family with Lynch syndrome tended to develop CRC earlier in life. Amsterdam criteria can be helpful in identifying Lynch syndrome

Related blog posts:

- Colorectal Cancer in Patients Up to Age to 25 Years

- Approach to Fundic Gland Polyps and VCE for Polyposis Syndromes

- Surprising Genetic Mutations in Polyposis Study

- ESPGHAN Juvenile Polyposis Syndrome in Children –Position Paper

- What I Like About ESPGHAN Familial Adenomatous Polyposis Position Paper -reviews many topics including CHRPE

- Cold vs Hot Polypectomy for Small Polyps

- Polyposis in Pediatric Patients -Review

- Blog Case Report: Colonic Polyp & Elevated Calprotectin

- Updated Guidelines on Genetic Testing/Management for Hereditary GI Cancer Syndromes (2015)

- The Latest on Lynch Syndrome

Disclaimer: This blog, gutsandgrowth, assumes no responsibility for any use or operation of any method, product, instruction, concept or idea contained in the material herein or for any injury or damage to persons or property (whether products liability, negligence or otherwise) resulting from such use or operation. These blog posts are for educational purposes only. Specific dosing of medications (along with potential adverse effects) should be confirmed by prescribing physician. Because of rapid advances in the medical sciences, the gutsandgrowth blog cautions that independent verification should be made of diagnosis and drug dosages. The reader is solely responsible for the conduct of any suggested test or procedure. This content is not a substitute for medical advice, diagnosis or treatment provided by a qualified healthcare provider. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a condition.