Over the next 2 weeks or so, I am posting my notes/pictures from this year’s annual meeting. The first few days will review the postgraduate course. For the most part, I find the postgraduate course reassuring that I have kept up with current approaches; there is usually not a lot of new information but a solid review of the topics.

Here is a link to postgraduate course syllabus: NASPGHAN PG Syllabus – 2017

This blog entry has abbreviated/summarized these presentations. Though not intentional, some important material is likely to have been omitted; in addition, transcription errors are possible as well.

Strictures beyond the esophagus

Petar Mamula, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia

Some useful points:

- Fluoroscopy very useful with most strictures –may improve safety and effectiveness. Helps define anatomy

- Reviewed strictures in stomach –rare. May be due to caustic ingestion, Crohn’s disease or chronic granulomatous disease

- Intestinal/colonic strictures (or narrowing): duodenal webs -can be treated with needle knife, Crohn’s disease strictures -can be balloon dilated, Short gut syndrome, Graft versus host disease

GI Bleeding Update

Diana Lerner Medical College of Wisconsin

Useful points

Upper GI Bleeding:

- IV PPIs reduce risk of transfusion and reduce risk of re-bleeding

- IV PPI BID treatment has been shown to be noninferior to continuous drip

- Conservative transfusion therapy

- Erythromycin can be helpful

- Lecture had good videos with review of techniques: clipping, heater probe, epinephrine injection (not recommended as monotherapy), argon plasma coagulation, and bipolar electrocautery

Lower GI Bleeding:

- Etiologies include the followiing: Post-polypectomy, Solitary Rectal Ulcer syndrome, Blue Rubber Bleb syndrome, anastomotic ulcer bleeding, Meckel’s diverticulum

- Lower GI evaluation is best after prep –much higher yield

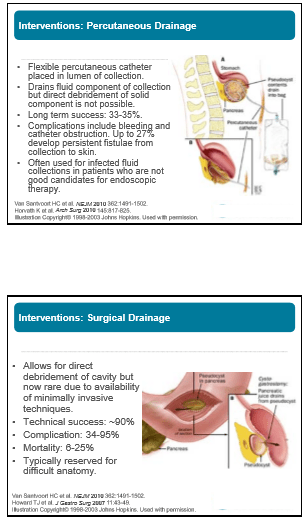

Management of Pancreatic Fluid Collections

Matt Giefer Seattle Children’s Hospital

Key points:

- Imaging in first 7 days of diagnosis may miss the development of fluid collections

- With necrotizing pancreatitis, fluid collections are either ANC: acute necrotic collection (<4 weeks) or WON: walled off necrosis (>4 weeks); Bryan et al. Radiographics 2016; 36: 675

- With interstitial edematous pancreatitis, fluid collections are either acute peripancreatic fluid collection (<4 weeks) or Pseudocyst: >4 weeks,

- Fluid collections do not preclude feeding patients

- Drainage often needed if fluid collection becomes infected or if fluid collection causes obstruction

- Endoscopic drainage is first-line approach: equally effective as surgery, fewer complications, equal efficacy, and lower cost