NA Marston et al. NEJM 2026; 394: 429-441. Olezarsen for Managing Severe Hypertriglyceridemia and Pancreatitis Risk

Background: “Severe hypertriglyceridemia, defined as a serum triglyceride level of 500 mg per deciliter or higher (≥5.65 mmol per liter), affects approximately 1 in 100 persons and can have clinical consequences, including an increased risk of life-threatening acute pancreatitis. Conventional triglyceride-lowering therapies, such as fibrates and n–3 fatty acids, often have modest effects on the triglyceride level and have not been shown to reduce the risk of acute pancreatitis.3“

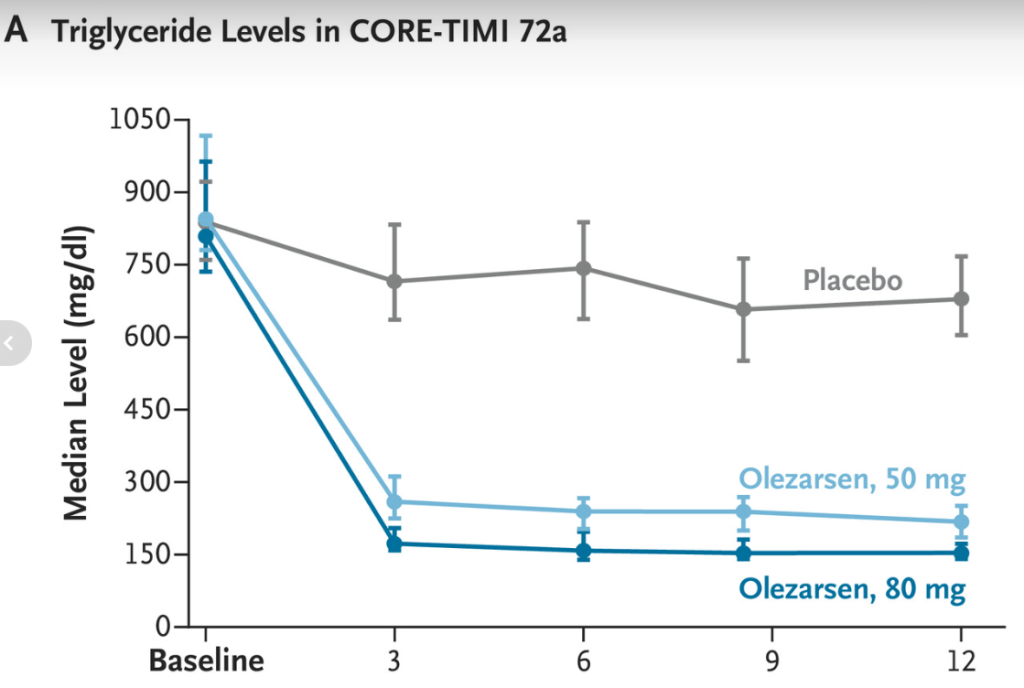

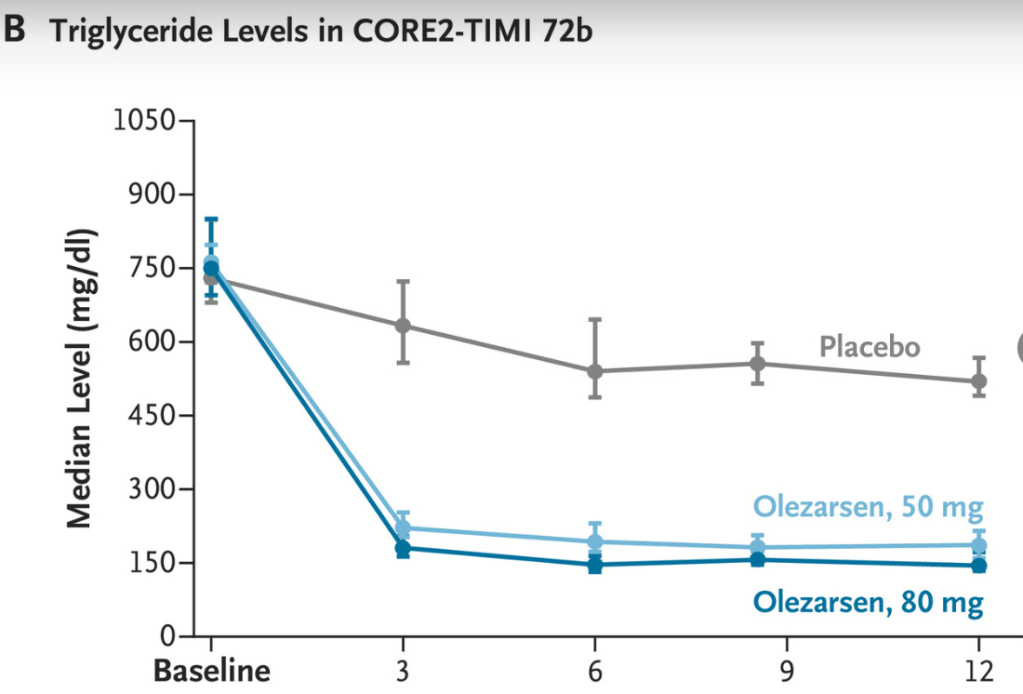

This study examined the efficacy and safety of olezarsen, an antisense oligonucleotide targeting apolipoprotein C-III messenger RNA. Olezararsen has already been shown to be effective in genetically identified familial chylomicronemia syndrome. This study targeted individuals with less extreme forms of hypertriglyceridemia (mean baseline triglyceride level of 793 mg/dL).

Key findings:

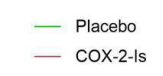

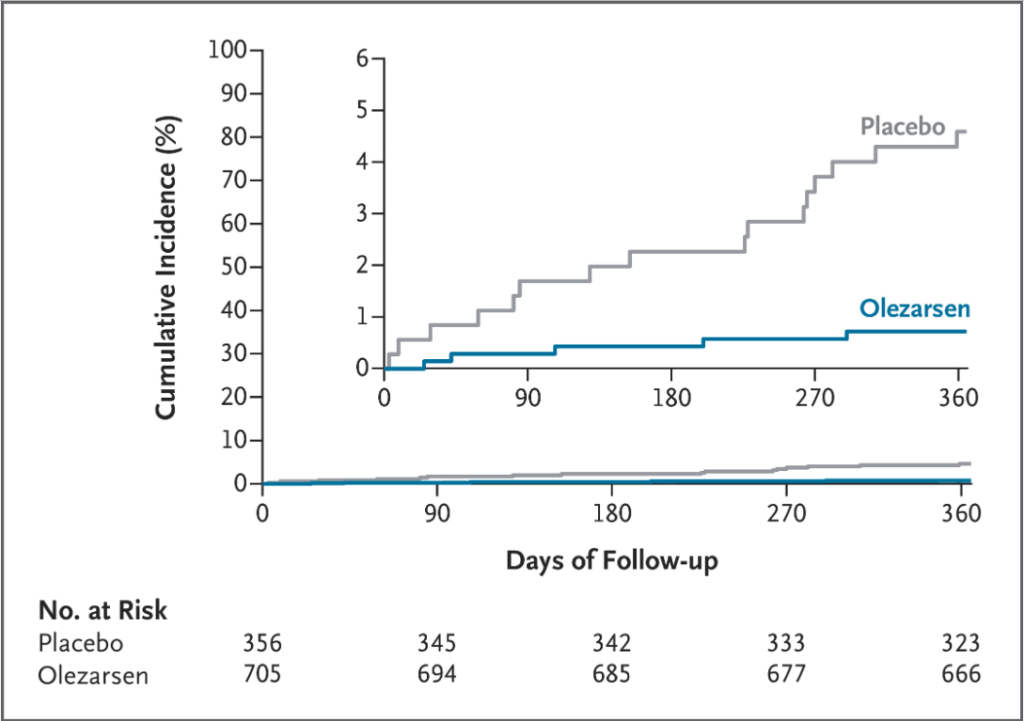

Incidence of Acute Pancreatitis

Adverse Effects:

- The incidence of any adverse events appeared to be similar across trial groups. Elevations in liver-enzyme levels and thrombocytopenia (platelet count, <100,000 per microliter) were more common with the 80-mg dose of olezarsen, and a dose-dependent increase in the hepatic fat fraction was noted.

- During the 1-year trial, major adverse cardiovascular events occurred in 2.0% of the pooled olezarsen group and 2.5% of patients receiving placebo.

My take: It is likely that olezarsen will have cardiovascular benefits as well as reducing the risk of pancreatitis in those with severe hypertriglyceridemia; though, these potential benefits await long-term studies.

Related blog posts: