MA Colak et al. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2026;82:358–365. Improvement in bile drainage after Kasai portoenterostomy with a tailored steroid protocol

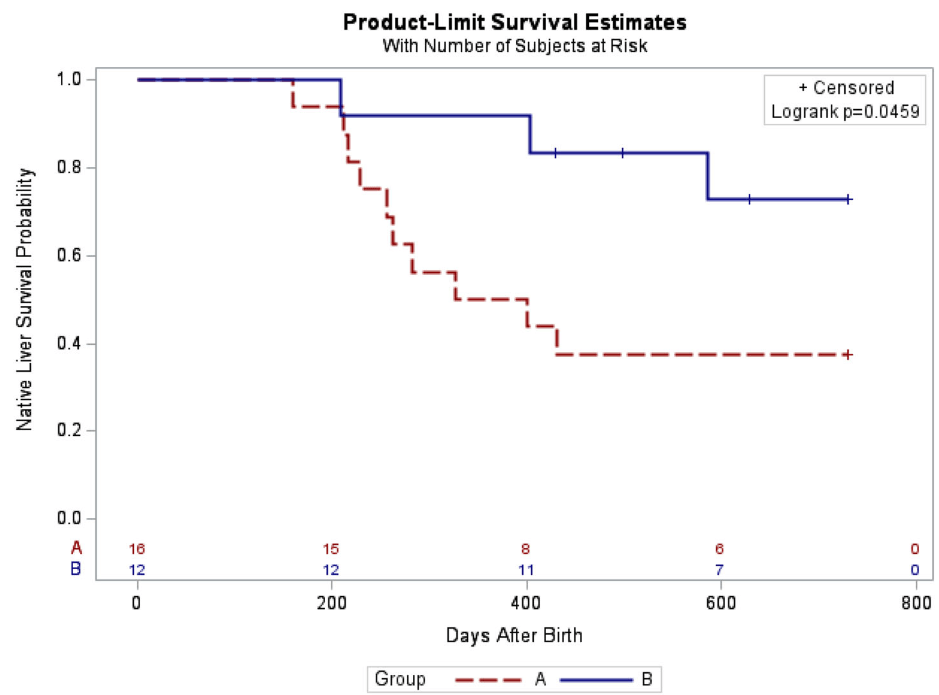

In this retrospective study, 28 infants underwent KPE between 2015 and 2025. Group A had 16 infants managed without steroids between 2015 and 2021, while Group B included 12 infants managed under the new tailored steroid protocol between 2021 and 2025.

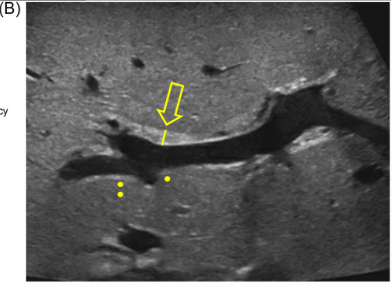

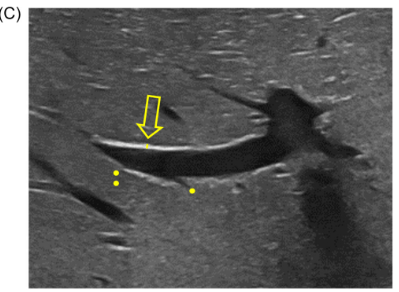

Determination of bile drainage: Postoperative stool color is monitored closely and collaboratively by hepatologists and surgeons according to the Japanese Tochigi Prefecture 3rd Edition stool card to assess bile drainage over the first five postoperative days.23 Patients with ≥50% of stools at color ≤3 are considered to have poor bile drainage, while those with >50% of stools at color ≥4 are considered to have good bile drainage.

Tailored steroid protocol: “If patients have poor bile drainage, further management depends on age at time of operation. Patients ≤45 days old at operation are started on a combined steroid and antibiotic treatment immediately after bile leak is ruled out using abdominal ultrasound. Patients >45 days old at operation are started on the steroid and antibiotic treatment only if the liver biopsy obtained during operation demonstrated acute inflammation on histology.”

Key findings:

- The 3-month post-KPE TB levels were significantly lower in Group B compared to Group A (0.9 [0.3, 1.9] mg/dL vs. 6.5 [0.6, 10.4] mg/dL, p = 0.036)

- The 2-year NLS was also significantly higher in Group B (72.9% vs. 37.5%, p = 0.046)

- LOS, readmissions, reoperations, and complications in the 90-day postoperative period were not different between both groups

In their discussion, the authors note that the “multicenter, placebo-controlled, double-blinded steroids in biliary atresia randomized trial (START) included 140 patients from the United States and assessed the effect of high-dose steroids (4 mg/kg/day).16 There was no significant difference in jaundice clearance at 6 months after operation (58.6% vs. 48.6%), nor significant difference in NLS at 2 years of age (58.7% vs. 59.4%) between the steroid and placebo groups.”

However, subsequently, “similar to our study, Pandurangi et al. also reported a significant increase in the ratio of patients who had a TB level of <2 mg/dL at 3 months after operation in the customized steroid protocol cohort. However, although the steroid protocol cohort had greater 2-year NLS (68.8% vs. 50%), the difference did not reach statistical significance in their study.

My take: The START study (n=140), which was powered to detect a 25% absolute treatment difference in TB levels, cannot exclude modest benefits from steroids. This study, despite its limitations, showed that a tailored protocol for use of steroids may improve outcomes.

Related blog posts:

- Customized Postoperative Therapy for Biliary Atresia -Does It Help?

- Rectal Budesonide for Biliary Atresia After Kasai Procedure

- Cholangitis After Kasai Procedure for Biliary Atresia

- START Study: Steroids Not Effective For Biliary Atresia (After Kasai) In this study, the steroid intervention did not affect transplant-free survival which was 58.7% in the steroid group and 59.4% in the placebo group at 24 months of age. In addition, steroids were associated with an earlier onset of first serious adverse events.

- Dr. Jorge Bezerra: Improving the Care of Children with Biliary Atresia

- “What Makes A “Successful” Kasai Portoenterostomy “Unsuccessful”?

- Bad News Bili

Disclaimer: This blog, gutsandgrowth, assumes no responsibility for any use or operation of any method, product, instruction, concept or idea contained in the material herein or for any injury or damage to persons or property (whether products liability, negligence or otherwise) resulting from such use or operation. These blog posts are for educational purposes only. Specific dosing of medications (along with potential adverse effects) should be confirmed by prescribing physician. Because of rapid advances in the medical sciences, the gutsandgrowth blog cautions that independent verification should be made of diagnosis and drug dosages. The reader is solely responsible for the conduct of any suggested test or procedure. This content is not a substitute for medical advice, diagnosis or treatment provided by a qualified healthcare provider. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a condition.