A Rubio-Tapia et al. Gastroenterol 2024; 166: 930-934. Open Access! AGA Clinical Practice Update on Diagnosis and Management of Cannabinoid Hyperemesis Syndrome: Commentary

Key points:

- Epidemiology: The prevalence of CHS (cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome) is rising and it is becoming a frequent clinical problem, leading to visits to the emergency department (ED) and gastroenterology clinics.5

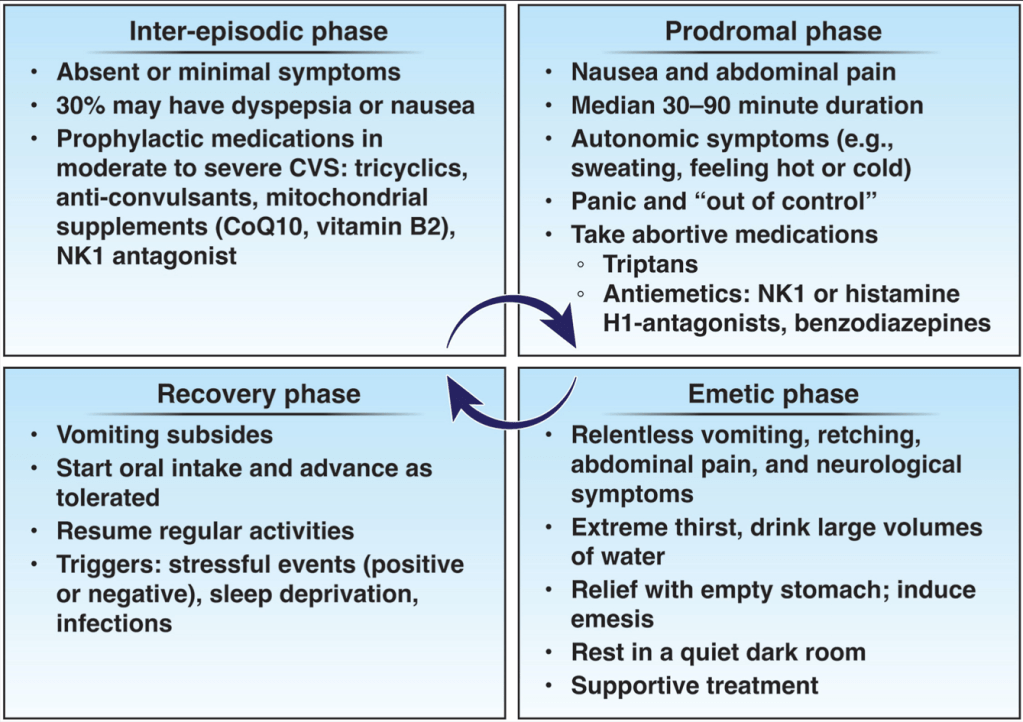

- Diverse Vomiting Patterns: Cannabis is associated with CVS, CHS, cannabinoid withdrawal syndrome (CWS), and nausea and vomiting in pregnancy. CVS is a relatively frequent presentation (10.8%) among patients with intermittent episodes of nausea and vomiting seeking care in outpatient gastroenterology clinics.23

- Presentation: CHS is characterized by cyclic vomiting, nausea, and abdominal pain; in some cases, CHS is associated with prolonged bathing behavior (long hot baths or showers). Although hot-water bathing pattern is not really pathognomonic of CHS because it is also reported in CVS,10 it is commonly considered as an indicator of CHS among community adults with CVS. In a systematic review of 271 cases of CHS, mean age was 30 years, 69% were male, mean duration of cannabis use before symptom onset was 6.6 years, daily use occurred in 68%, and hot-water bathing was reported in 71% of patients.e7 CHS should be suspected in patients with chronic nausea and vomiting and cannabis use.

- Management: Evidence to support treatment for CHS is limited … supporting the use of topical capsaicin, benzodiazepines, haloperidol, promethazine, olanzapine, and ondansetron for acute and short-term care. Topical capsaicin may improve symptoms by activation of transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1 receptors. Opioids should be avoided due to worsening of nausea and high risk of addiction.

- Management (Long-term): Counseling to achieve marijuana cessation and tricyclic antidepressants, such as amitriptyline, are the mainstay of therapy, with the minimal effective dose being 75–100 mg at bedtime, starting at 25 mg and titrating the dose with increments each week to reach minimal effective dose with a close monitoring of efficacy and adverse effects……Observational experience suggests that a tricyclic antidepressant, such as amitriptyline [may help with withdrawal symptoms]

My take: The most cyclical (cynical) part of CHS is the stereotypical attempt to get patients to stop using cannabis.

As an aside, cannabis use is often disclosed by patients having procedures and their atypical response to sedation/anesthesia. Use of anesthetics including propofol can have cross-reactivity with cannabis. In addition, several studies have demonstrated that cannabis users are more likely to report higher pain scores, poorer sleep, and require a greater quantity of analgesic medications in the immediate postoperative period than nonusers.

Related blog posts:

- Cannabis Toxic Effects

- Does Stopping Cannabis Improve Cyclic Vomiting Syndrome?

- Legalized Cannabis Associated with Increased Vomiting and Dependency But What About Alcohol?

- Neuro-Stim for Refractory Cyclic Vomiting?

Disclaimer: This blog, gutsandgrowth, assumes no responsibility for any use or operation of any method, product, instruction, concept or idea contained in the material herein or for any injury or damage to persons or property (whether products liability, negligence or otherwise) resulting from such use or operation. These blog posts are for educational purposes only. Specific dosing of medications (along with potential adverse effects) should be confirmed by prescribing physician. Because of rapid advances in the medical sciences, the gutsandgrowth blog cautions that independent verification should be made of diagnosis and drug dosages. The reader is solely responsible for the conduct of any suggested test or procedure. This content is not a substitute for medical advice, diagnosis or treatment provided by a qualified healthcare provider. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a condition.