TG DeLoughery et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2024; 22: 1575-1583. Open Access! AGA Clinical Practice Update on Management of Iron Deficiency Anemia: Expert Review

This guideline was developed with adults in mind; however, much of the practice advice is applicable in the pediatric population as well. Here are some of the recommendations:

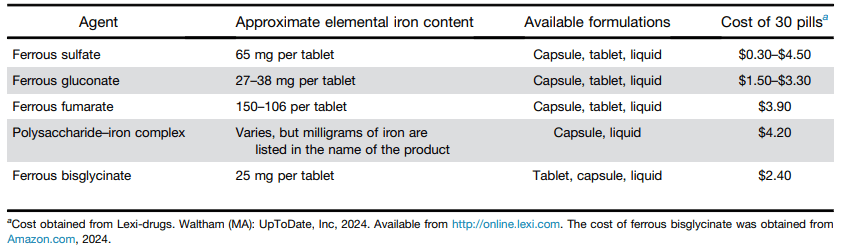

- Best Practice Advice 1: No single formulation of oral iron has any advantages over any other. Ferrous sulfate is preferred as the least expensive iron formulation.

- Best Practice Advice 2: Give oral iron once a day at most. Every-other-day iron dosing may be better tolerated for some patients with similar or equal rates of iron absorption as daily dosing.

- Best Practice Advice 3: Add vitamin C to oral iron supplementation to improve absorption.

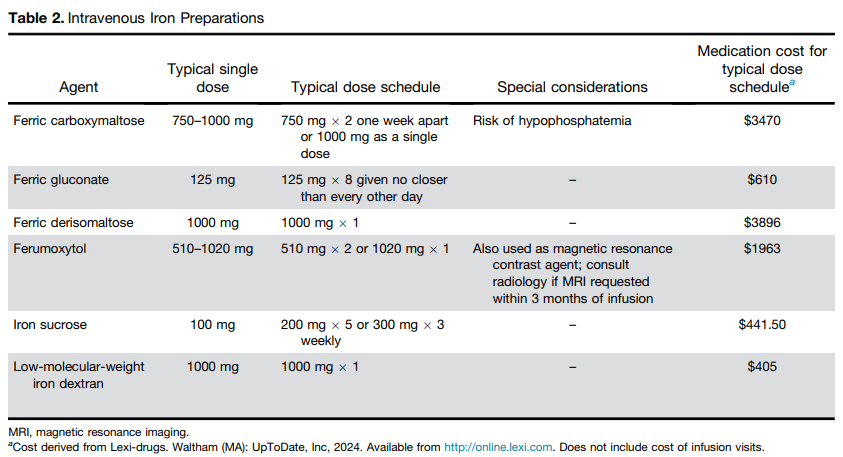

- Best Practice Advice 4: Intravenous iron should be used if the patient does not tolerate oral iron, ferritin levels do not improve with a trial of oral iron, or the patient has a condition in which oral iron is not likely to be absorbed.

- Best Practice Advice 5: Intravenous iron formulations that can replace iron deficits with 1 or 2 infusions are preferred over those that require more than 2 infusions.

- Best Practice Advice 6: All intravenous iron formulations have similar risks; true anaphylaxis is very rare. The vast majority of reactions to intravenous iron are complement activation–related pseudo-allergy (infusion reactions) and should be treated as such.

With regard to iron infusion reactions, the authors note the following:

Being truly allergic to IV iron is very rare—almost all reactions are complement activation–related pseudo-allergy, which are idiosyncratic infusion reactions that can mimic allergic reactions.26 For mild reactions, simply stopping the infusions and restarting 15 minutes later at a slower rate will suffice. For more severe reactions, corticosteroids may be of benefit. Diphenhydramine should be avoided because its side effects of mouth dryness, tachycardia, diaphoresis, somnolence, and hypotension can be mistaken for worsening of the reaction.27 Studies have shown that rates of mild reactions are approximately 1:200 and rates of major reactions are approximately 1:200,000.28

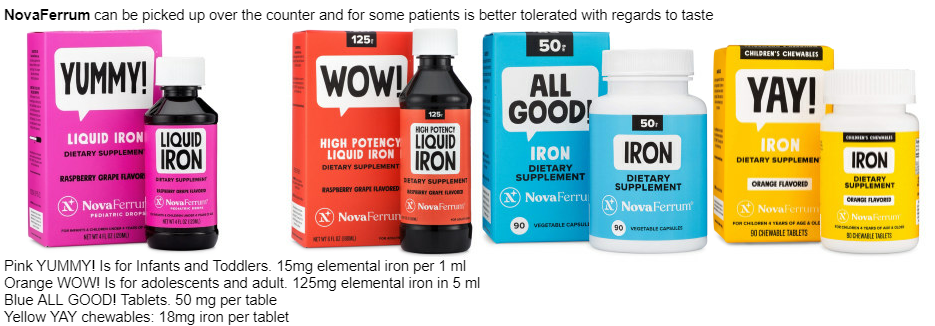

Related information: Our hematologists often recommend Novaferrum (polysaccharide-iron complex) products in children.

Food/diet items with plenty of iron:

- beef, pork, poultry, and seafood

- tofu

- dried beans and peas

- dried fruits

- leafy dark green vegetables

- iron-fortified breakfast cereals, breads, and pastas

- Use of “lucky fish” (also available at Amazon) while cooking and cooking with cast iron pan can increase iron intake. The lucky fish can be used for 5 years.

Limiting milk consumption can help improve iron absorption.

My take: Iron deficiency anemia is a common issue in pediatric gastroenterology that usually merits evaluation. The AGA practice update provides helpful information with regard to management.

Related blog posts:

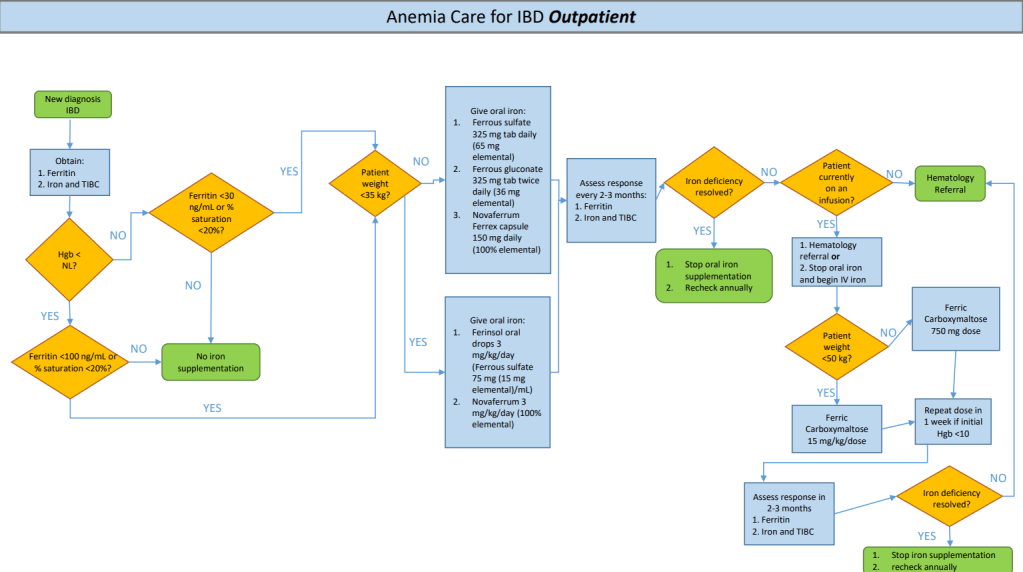

- Changing Approach to Iron Deficiency Anemia in Pediatric IBD

- Anemia in IBD -NASPGHAN Position Paper

- CHOP QI: Anemia in IBD Pathway

- IV Versus Oral Iron in Children with Anemia –POPEYE Study

- Changing Threshold for Blood Transfusion for Iron Deficiency Anemia

- Patient Handout from AGA on Iron Deficiency Anemia

- Iron Injectables

- AGA Guidance: Nutritional Therapies for Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- Iron Deficiency Common in Patients Requiring Long-Term Parenteral Nutrition

Disclaimer: This blog, gutsandgrowth, assumes no responsibility for any use or operation of any method, product, instruction, concept or idea contained in the material herein or for any injury or damage to persons or property (whether products liability, negligence or otherwise) resulting from such use or operation. These blog posts are for educational purposes only. Specific dosing of medications (along with potential adverse effects) should be confirmed by prescribing physician. Because of rapid advances in the medical sciences, the gutsandgrowth blog cautions that independent verification should be made of diagnosis and drug dosages. The reader is solely responsible for the conduct of any suggested test or procedure. This content is not a substitute for medical advice, diagnosis or treatment provided by a qualified healthcare provider. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a condition.