- L Aceituno, J Banares et al. Gastroenterol 2026; 170: 385-394. Open Access! The ANTICIPATE-NASH Models Stratify Better the Risk of Clinical Events Than Histology in Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease Patients With Advanced Chronic Liver Disease

- L Castera. Gastroenterol 2026; 170: 257-259. Editorial. Open Access! Refining Risk Stratification in Metabolic Dysfunction–Associated Steatotic Liver Disease: Moving Beyond Histology With Individualized Noninvasive Predictive Models for Clinical Events

The editorial provide a succinct critique and summary of this retrospective study. An excerpt:

For many decades, liver biopsy specimens and HVPG measurements have served as the cornerstone for risk stratification of patients with cirrhosis. Fibrosis staging, particularly the distinction between F3 and F4, as well as HVPG measurements, have informed prognoses and patient enrollment in therapeutic trials…

Noninvasive tests, particularly liver stiffness measurement (LSM) by vibration-controlled transient elastography (VCTE), are increasingly used for risk stratification in MASLD patients with cirrhosis and may inform treatment decisions.3 The ANTICIPATE–nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) models, which combine LSM, platelet count, and body mass index, have been proposed to predict the risk of CSPH [clinically significant portal hypertension] progression and liver-related events (LRE) in patients with MASLD.4–6 …

First, the authors examined a multicenter cohort of 699 biopsy specimen–proven MASLD patients with LRE (hepatic decompensation, hepatocellular carcinoma, transplantation, or liver-related death) as the end point. Second, they examined a validation cohort of 1396 F3 or F4 patients from 4 clinical trials…

The results can be summarized as follows: In the first cohort, 56 LREs (8%) occurred during a 3-year follow-up, mostly in F4 patients. The second cohort had 33 composite end points (2.3%) during a median follow-up of 16 months. The ANTICIPATE-NASH model showed excellent discrimination for LRE (C statistic, 0.93), which was higher than that for histology (C statistic, 0.67). However, adding histology to the model did not improve prediction… These findings highlight the limitations of biopsy specimens and underscore the ability of noninvasive models to capture the dynamic and continuous nature of disease progression…

The clinical and research implications are substantial. In daily clinical practice, the widespread adoption of the ANTICIPATE-NASH model could allow hepatologists to identify high-risk patients who require closer monitoring or early therapeutic intervention while sparing low-risk patients from invasive biopsies and unnecessary procedures. For clinical trials, model-based enrichment could increase event rates, reduce required sample sizes, and shorten follow-up duration.

My take: This study, while limited by its retrospective design, indicates that histology is no longer the “gold” standard for prognostication in adults with MASLD and advanced fibrosis.

Related blog posts:

- Prevalence of Steatotic Liver Disease in U.S. And Risk of Complications

- Limitations of MRE and TE in Assessing Liver Fibrosis in Pediatric MASLD

- AASLD Practice Statement on the evaluation and management of metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease in children (2025)

- Key Insights on MASLD from Dr. Marialena Mouzaki

- More Pediatric Data Supporting GLP-1 RA Efficacy for MASLD

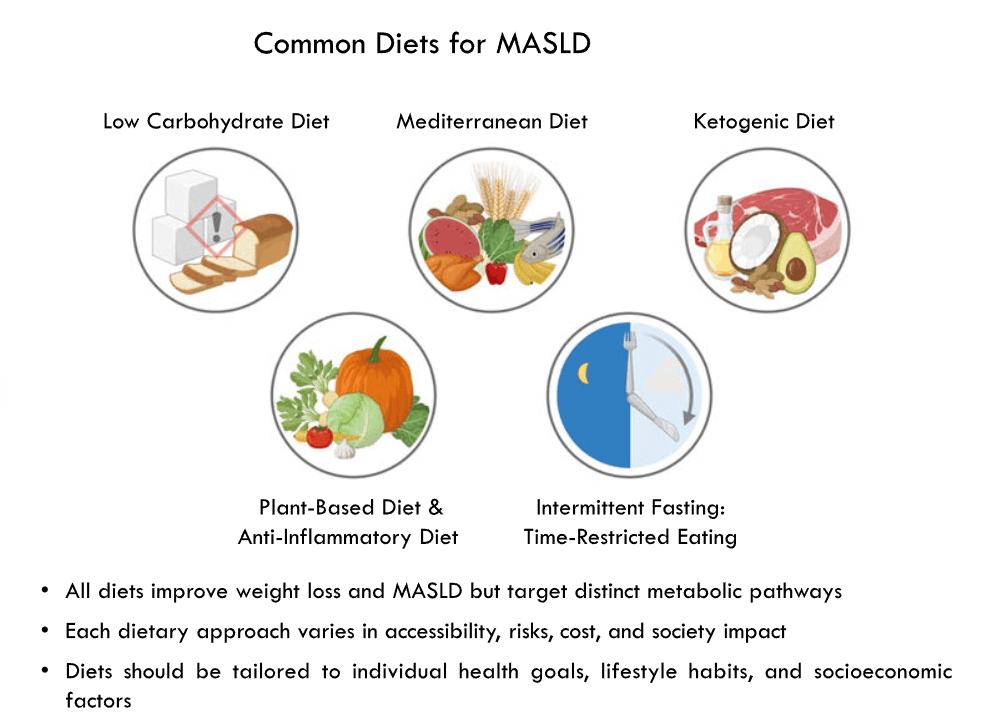

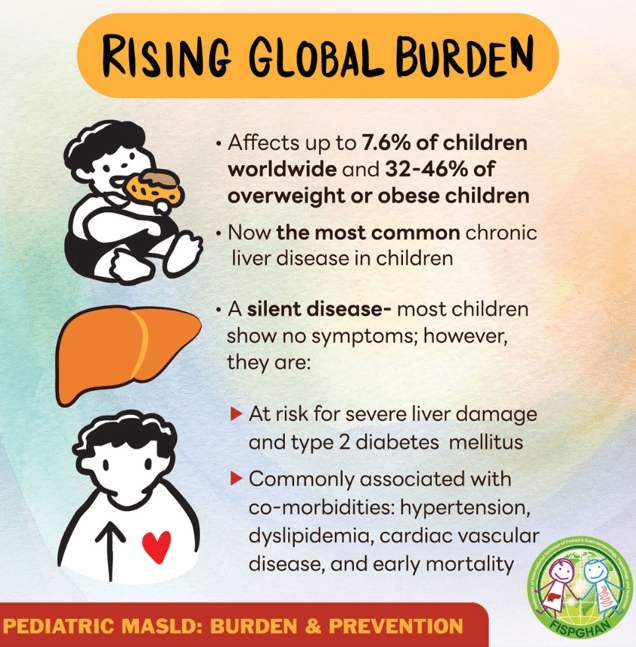

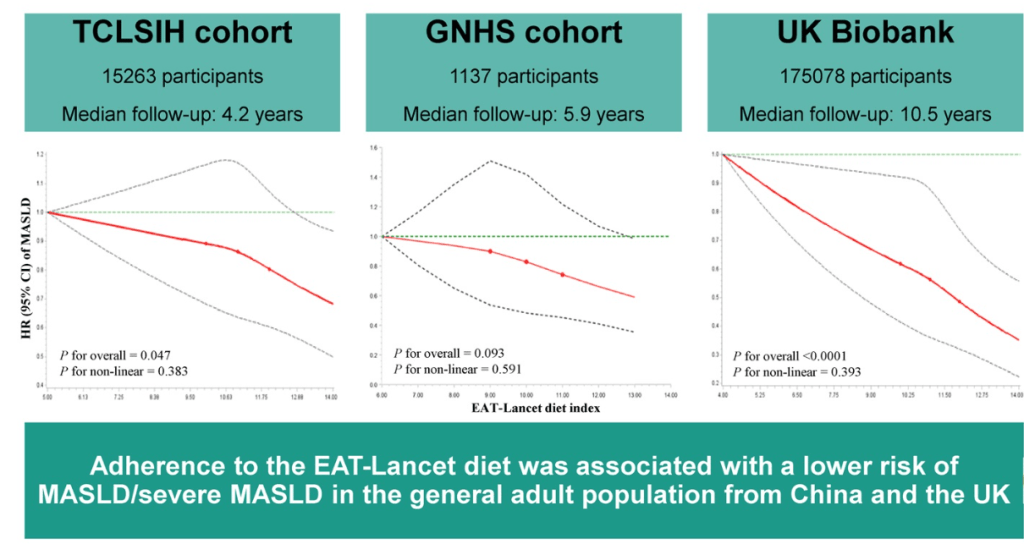

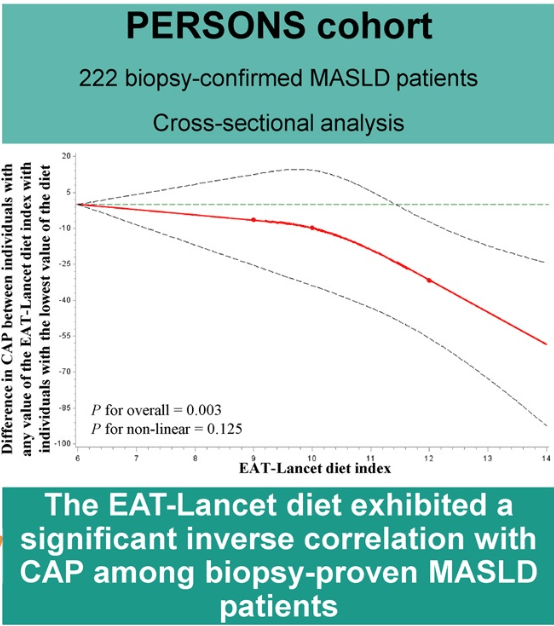

- Diets for Obesity and Steatotic Liver Disease Plus Patient Information from FISPGHAN