WS Thompson et al. Liver Transplantation 2023; 29: 118-121. Ultra-rapid whole genome sequencing: A paradigm shift in the pre-transplant evaluation of neonatal acute liver failure

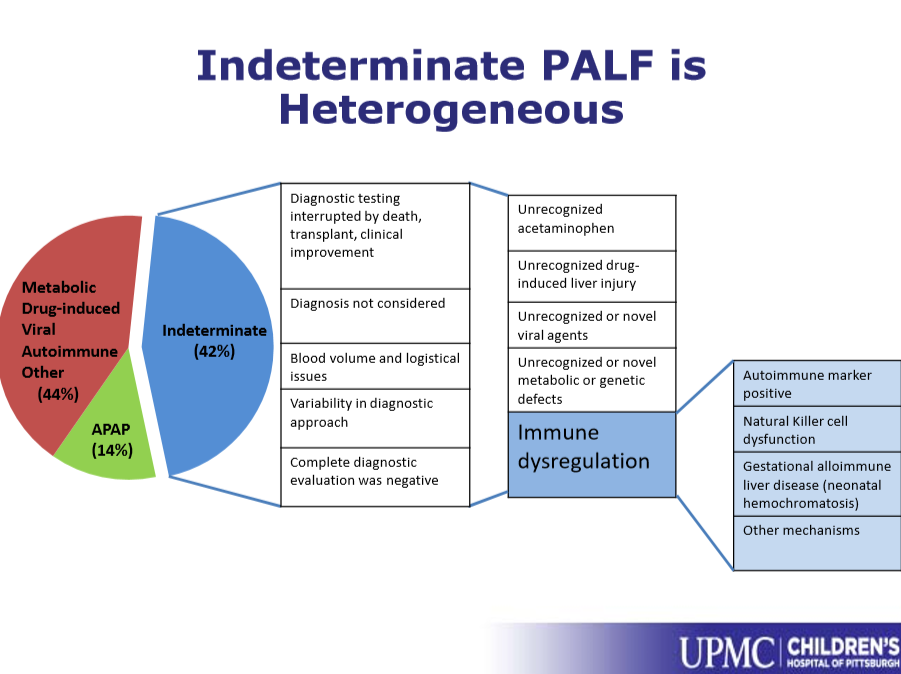

In this case series, three patients had ultra-rapid whole genome sequencing (WGS). Case 1 identified PRF1 mutation consistent with familial HLH, Case 2 identified variants in FDXR implicated in a mitochondrial disorder and Case 3, found pathogenic mutations in ASL associated with agrininosuccinic aciduria.

The authors argue that ultra-rapid WGS which can provide information in as little as 12 hours and typically provides actionable results within 3 days. should be a first-line approach and would identify nearly all causative genetic reasons for neonatal acute liver failure. While GALD and viral etiologies would not be found, if there are no genetic causes, this would support the “initiation of empiric therapy.”

S Antala et al. Liver Transplantation 2023; 29: 5-14. Open Access! Neonates with acute liver failure have higher overall mortality but similar posttransplant outcomes as older infants

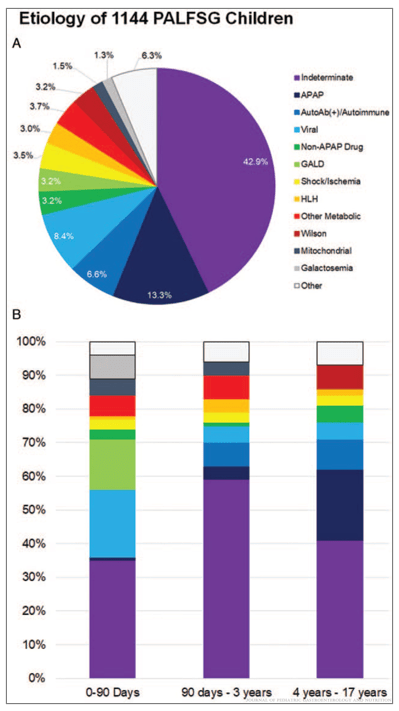

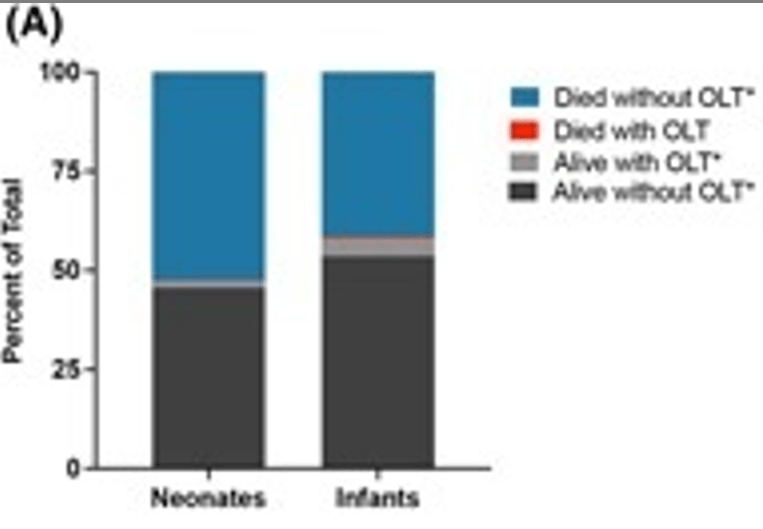

In this retrospective study with 1807 neonates and 890 infants (31-120 days) with ALF (identified in two large databases between 2004-2018), the key findings:

- Neonates had higher death rates (46% alive without liver transplant, compared to 53% of infants who were alive without liver transplant)

- Both groups had low liver transplant rates, with neonates less likely to be transplanted: 2% vs 6.4% (P<0.001)

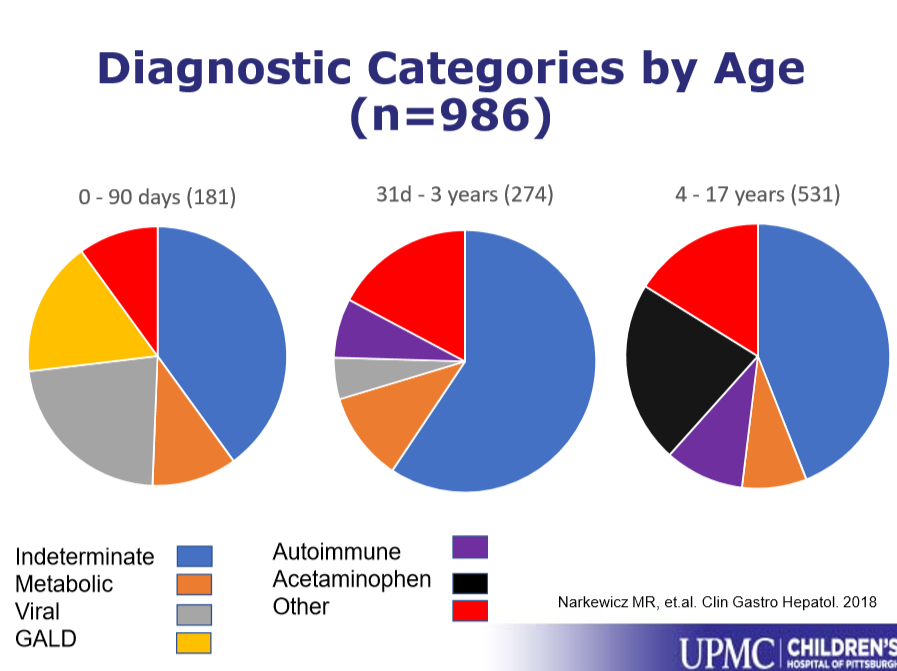

- Infants had higher rates of “unidentified” as etiology whereas neonates had higher rates of GALD and viral infections. Cardiac etiologies causing ALF were common in both groups, 24% of neonates and 18% of infants.

My take: Rapid genomic testing is very useful in infants/neonates with ALF. This population has a high mortality rate and a low rate of receiving liver transplants. Reducing the size for split liver donation could help with organ availability (see next post).

Related blog posts: