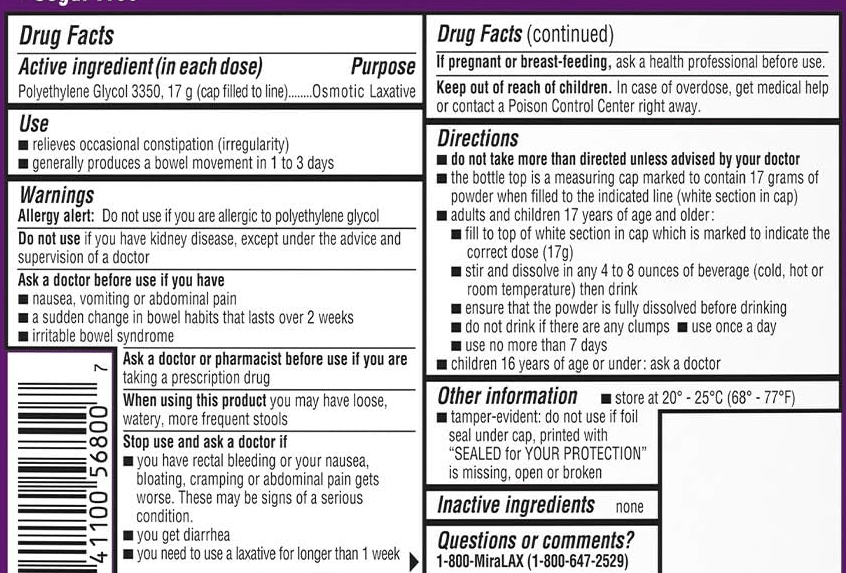

Clarification: Yesterday’s post on the safe use of polyethylene glycol (Long Term Use of Polyethylene Glycol (PEG 3350)) noted the labeling indicates “‘to not use these medications for more than 7 days.” However, Ben Enav pointed out that the label also states the following in bold: “do not take more than directed unless advised by your doctor.” The actual label is shown below.

———

SA Gutierrez et al. J Pediatr 2024; 265: 113819. Neighborhood Income Is Associated with Health Care Use in Pediatric Short Bowel Syndrome

Methods: The authors used the Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS) database to evaluate associations between neighborhood income and hospitalization data for children with short bowel syndrome (SBS). This included 4289 children with 16,347 hospitalizations from 43 institutions.

Key findings:

- 2153 of the 4289 (50%) patients were readmitted during the study period (2006-2015)

- Children living in low-income neighborhoods were more likely to be Black, Hispanic, have public health insurance, and live in the Southern U.S.

- Children from low-income neighborhoods had a 38% increased risk for all-cause hospitalizations (rate ratio [RR] 1.38), an 83% increased risk for CLABSI hospitalizations (RR 1.83) and increased hospital length of stay.

- 2.4% of patients in this cohort experienced 10 or more CLABSI hospitalizations

One of the study’s limitations is that ‘there is no singular ICD-9 code for SBS.’

My take: It is speculation about the reasons why children in low income neighborhoods have higher rates of hospitalizations and CLABSI hospitalizations. It could be that more parents in these households have less time and resources to manage a child with SBS. It is possible that these households have more chaotic environments. Regardless of the reason, it takes a lot of work and meticulous care to prevent CLABSI hospitalizations in children with SBS.

Related blog posts:

- Short Bowel Syndrome is a Full Time Job Caregivers reported a median of 29.2 hours per week of direct medical care.

- Antibiotic Selection for Suspected Central Line Infections

- Short Bowel Syndrome -YouTube Information