Full Text Link: ACG Clinical Guideline: Management of Crohn’s Disease. GR Lichtenstein et al. Am J Gastroenterol 2018; 113:481–517

A few of the recommendations from Table 1:

- (Insurance companies –please read this one): #1 Fecal calprotectin is a helpful test that should be considered to help differentiate the presence of IBD from irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) (strong recommendation, moderate level of evidence).

- #9 Perceived stress, depression, and anxiety, which are common in IBD, are factors that lead to decreased health-related quality of life in patients with

Crohn’s disease, and lead to lower adherence to provider recommendations. Assessment and management of stress, depression, and anxiety should beincluded as part of the comprehensive care of the Crohn’s disease patient (strong recommendation, very low level of evidence)

- #24, 25 Anti-TNF agents (infliximab, adalimumab, certolizumab pegol) should be used to treat Crohn’s disease that is resistant to treatment with corticosteroids (strong recommendation, moderate level of evidence). Anti-TNF agents should be given for Crohn’s disease refractory to thiopurines or methotrexate (strong recommendation, moderate level of evidence).

- #26 Combination therapy of infliximab with immunomodulators (thiopurines) is more effective than treatment with either immunomodulators alone or

inflximab alone in patients who are naive to those agents (strong recommendation, high level of evidence).

- #27 For patients with moderately to severely active Crohn’s disease and objective evidence of active disease, anti-integrin therapy (with vedolizumab) with

or without an immunomodulator is more effective than placebo and should be considered to be used for induction of symptomatic remission in patients withCrohn’s disease (strong recommendation, high level of evidence).

- #30 Ustekinumab should be given for moderate-to-severe Crohn’s disease patients who failed previous treatment with corticosteroids, thiopurines, methotrexate, or anti-TNF inhibitors or who have had no prior exposure to anti-TNF inhibitors (strong recommendation, high level of evidence).

- #46 Oral 5-aminosalicylic acid has not been demonstrated to be effective for maintenance of medically induced remission in patients with Crohn’s disease,

and is not recommended for long-term treatment (strong recommendation, moderate level of evidence).

- # 58 In high-risk patients, anti-TNF agents should be started within 4 weeks of surgery in order to prevent postoperative Crohn’s disease recurrence

(conditional recommendation, low level of evidence).

From Table 2:

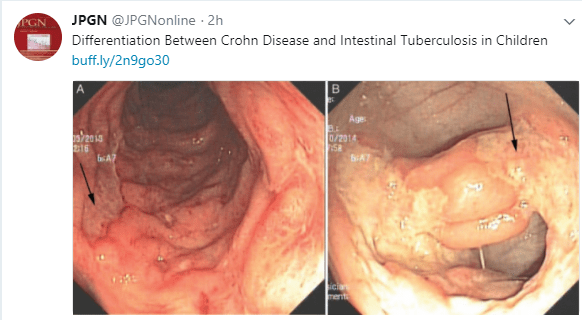

- #9 Symptoms of Crohn’s disease do not correlate well with the presence of active inflammation, and therefore should not be the sole guide for therapy. Objective evaluation by endoscopic or cross-sectional imaging should be undertaken periodically to avoid errors of under– or over treatment.

- #23 Routine use of serologic markers of IBD to establish the diagnosis of Crohn’s disease is not indicated.

- #30 Small bowel imaging should be performed as part of the initial diagnostic workup for patients with suspected Crohn’s disease.

- #44 Insufficient data exist to support the safety and efficacy of switching patients in stable disease maintenance from one biosimilar to another of the same biosimilar molecule.

Disclaimer: These blog posts are for educational purposes only. Specific dosing of medications/diets (along with potential adverse effects) should be confirmed by prescribing physician/nutritionist. This content is not a substitute for medical advice, diagnosis or treatment provided by a qualified healthcare provider. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a condition.