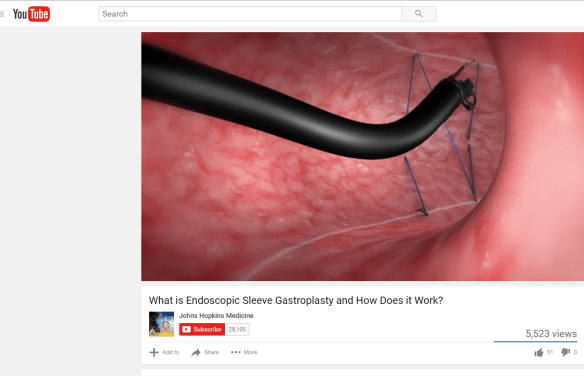

A recent study (BK A Dayyeh et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017; 15: 37-43) provides evidence that endoscopic sleeve gastoplasty can be an effective treatment for obesity.

AGA Website Summary Endoscopic Sleeve Gastroplasty: A Promising New Weight Loss Procedure

An excerpt:

In the fight against obesity, bariatric surgery is currently the most effective treatment; however, only 1 to 2 percent of qualified patients receive this surgery due to limited access, patient choice, associated risks and the high costs. A novel treatment method — endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty — might offer a new solution for obese patients. Endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty is a minimally invasive, safe and cost-effective weight loss intervention, according to a study1 published online in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association…

In this study of 25 patients with obesity who underwent the procedure at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, MN, endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty reduced excess body weight by 54 percent at one year. Further, the procedure delayed solid food emptying from the stomach and created an earlier feeling of fullness during a meal, which resulted in a more significant and long-lasting weight loss.

Endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty was well tolerated as an outpatient treatment, requiring less than two hours of procedure time. Patients resumed their normal lifestyle within one to three days. The treatment was performed using standard “off-the-shelf” endoscopic tools as opposed to specific weight loss devices or platforms. The cost of endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty is roughly one-third that of bariatric surgery.

4 minute YouTube description from Johns Hopkins: What is Endoscopic Sleeve Gastroplasty and How Does it Work?