PA Ubel et al. NEJM 2025; 392: 729-731. Out of Pocket Getting Out of Hand — Reducing the Financial Toxicity of Rapidly Approved Drugs

Key points:

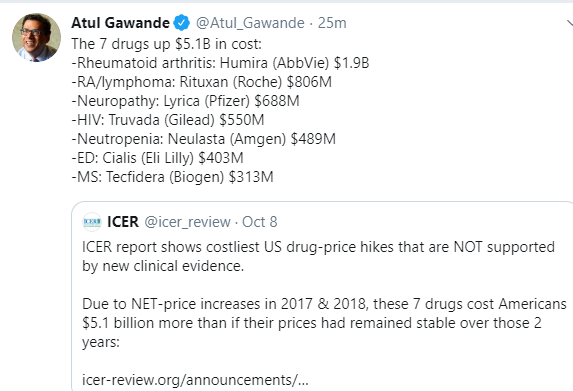

- In 2023, the median list price of new drugs was $300,000 per year. The FDA does not consider drug cost as part of its approval process.

- Many new drugs have uncertain benefits despite FDA approval. “Since the FDA is authorized to approve drug labeling, it could consistently require that labeling indicate when a drug’s approval was based on results from uncontrolled trials or from trials with surrogate measures…might reduce the chances that patients, seeing that a drug has FDA approval, will mistakenly assume that it has been proven to provide substantial benefits..[however] . In the face of serious illness, people frequently prefer action to inaction, even when they would ultimately be harmed by taking action.”

- Optimally, “congress would need to pass legislation giving the agency authority to consider financial harms when making decisions about drugs with unclear benefits, and the FDA would need to gain expertise in evaluating the budgetary implications of new drugs.”

My take: The financial burdens of newer medications leave patients unable to afford other necessary medical and non-medical expenses. This is especially problematic when a new medication offers minimal benefit.

Related blog posts:

- Financial Toxicity of Liver Transplantation and Cirrhosis

- Anti-TNF Therapy and Lower Rates of Colon Cancer & Financial Hardship Due to IBD

- Exorbitant Drug Costs from USA Today

- Tackling High Drug Costs -Lessons from Australia and Brazil

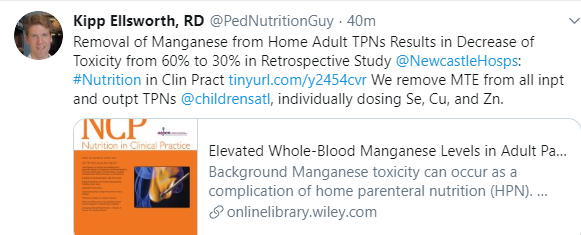

- Teduglutide Study on Parenteral Nutrition -It Does NOT Reduce Costs

- NPR: Drugmakers Claim to Lose Money in US In Order to Avoid Taxes

- Expect Costs of Liquid Omeprazole to Increase Due to FDA Approval

- Poster Child for Gaming Pharmaceutical Regulations: Humira