S Xanthakos et al. Hepatology 2025; 82: 1352-1394. AASLD Practice Statement on the evaluation and management of metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease in children (Behind paywall)

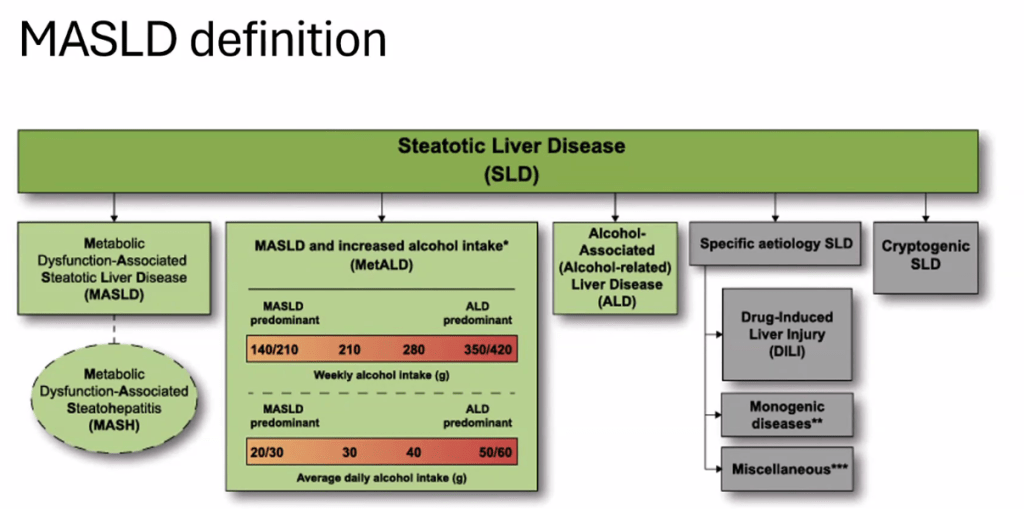

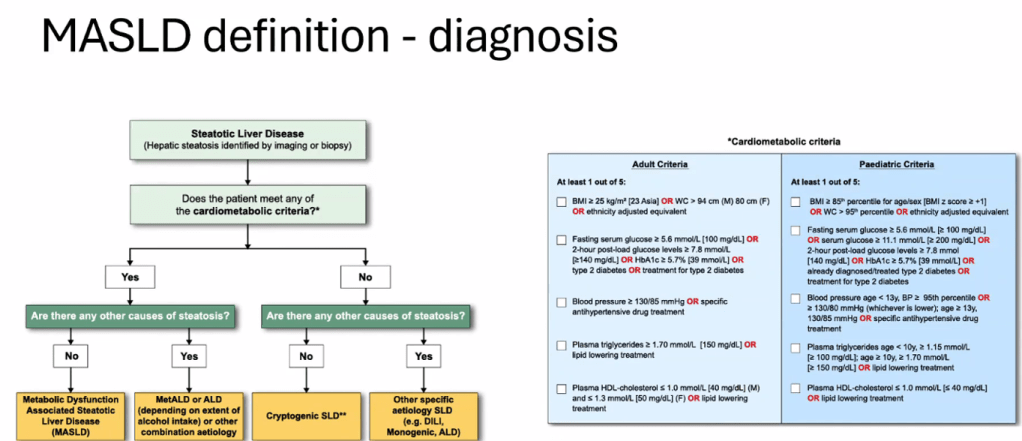

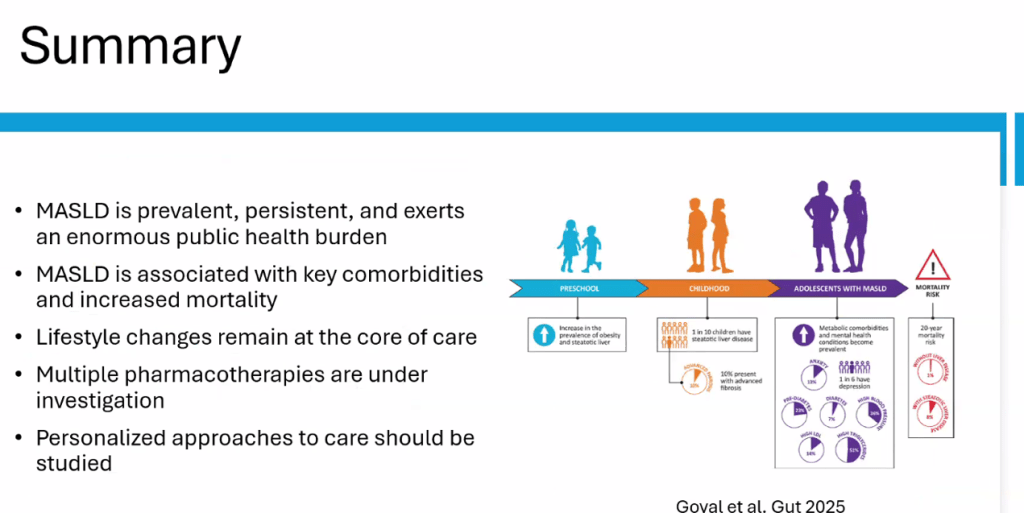

The review of pediatric MASLD addresses epidemiology, pathophysiology, natural history, screening, diagnosis, treatment, comorbidity management, outcome monitoring, and transition of care. It also discusses the implications of the 2023 nomenclature revision, which emphasizes evaluating both hepatic steatosis and cardiometabolic risk factors.

Some key points:

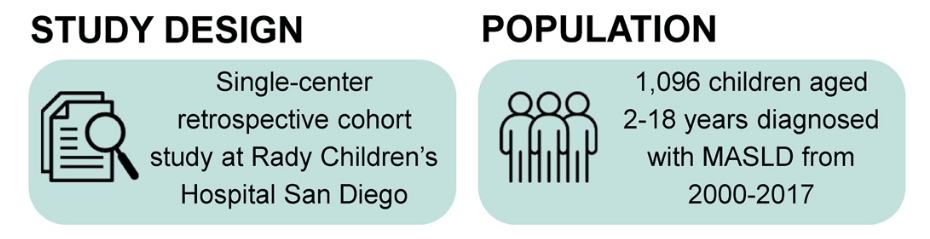

- Box 1 outlines numerous (32) research priorities, including the need for prospective longitudinal cohort studies.

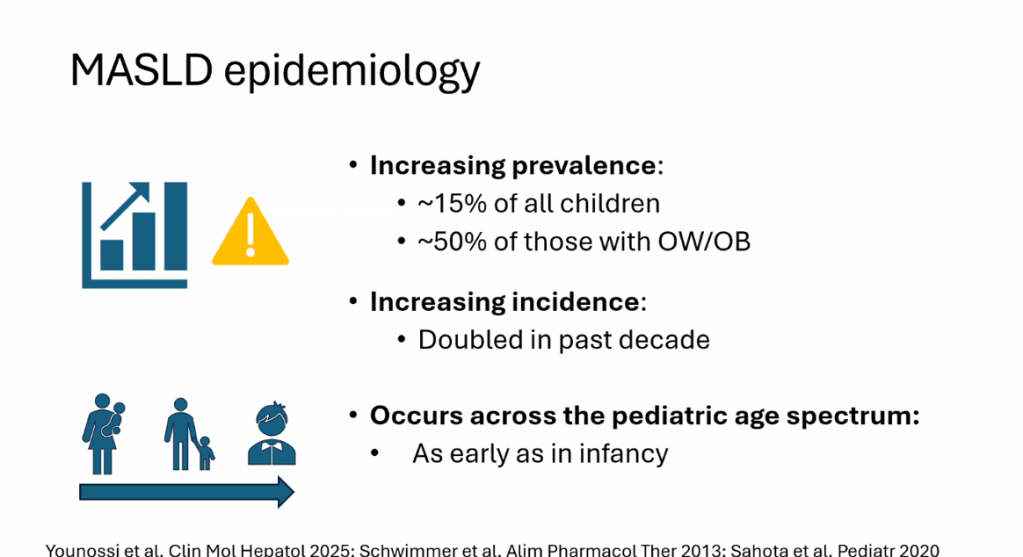

- “Globally, the estimated prevalence of MASLD in children is 7.6%, making it the most common cause of chronic liver disease in children”

- Figure 4 describes the interplay between risk factors for MASLD included genetic predisposition, prenatal factors and environmental exposures

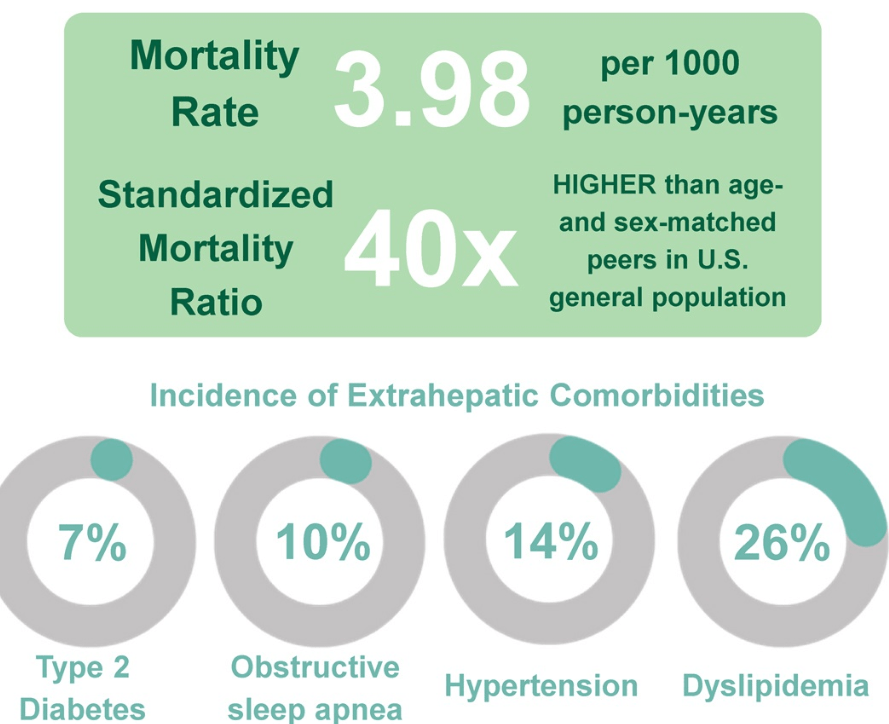

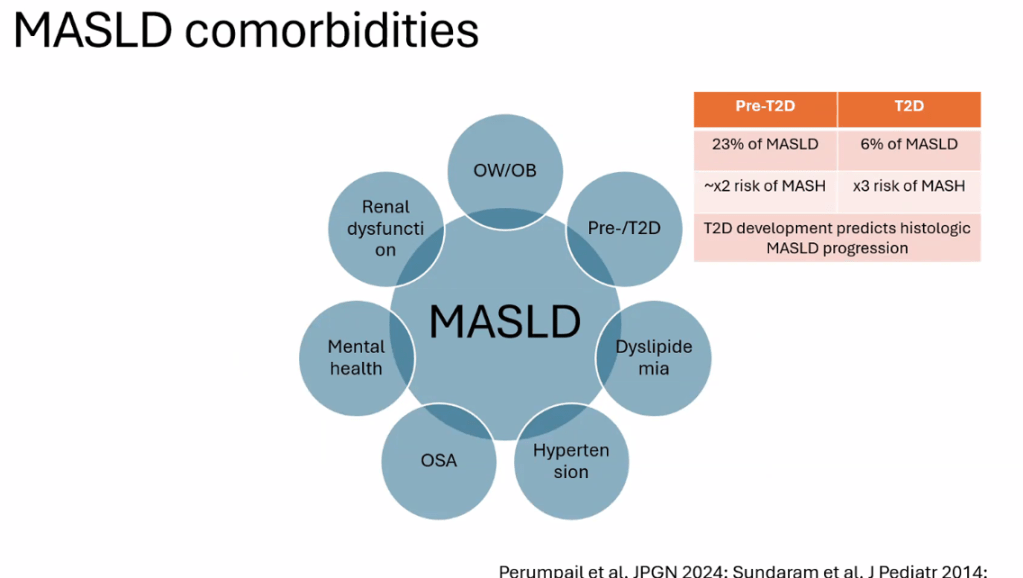

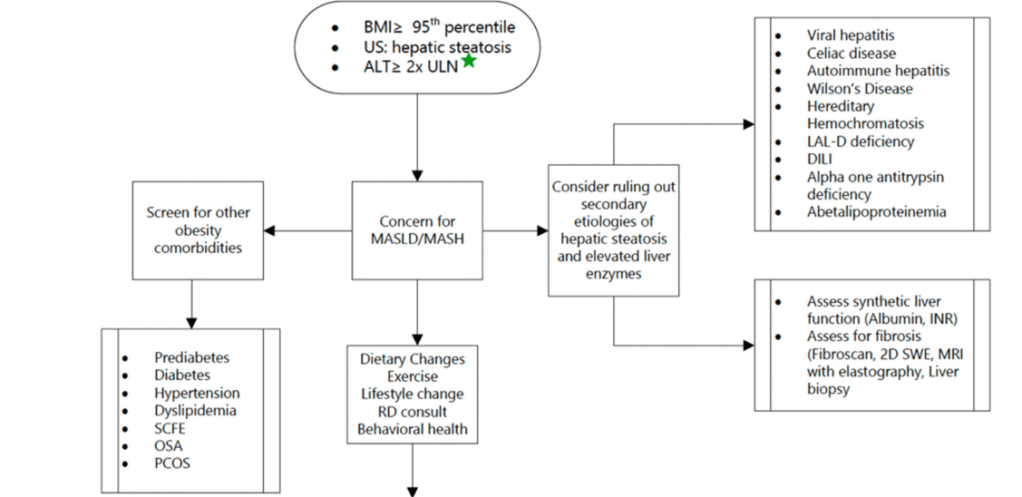

- Figure 5 summarizes comorbid conditions which include obstructive sleep apnea, prediabetes/diabetes, cardiovascular disease (dyslipidemia, hypertension, left ventricular hypertrophy), anxiety/depression, reduced bone mineral density, renal dysfunction and polycystic ovarian syndrome. Table 6 summarizes evaluation and initial management with most of these conditions. Yearly screening for diabetes in children with MASLD is recommended.

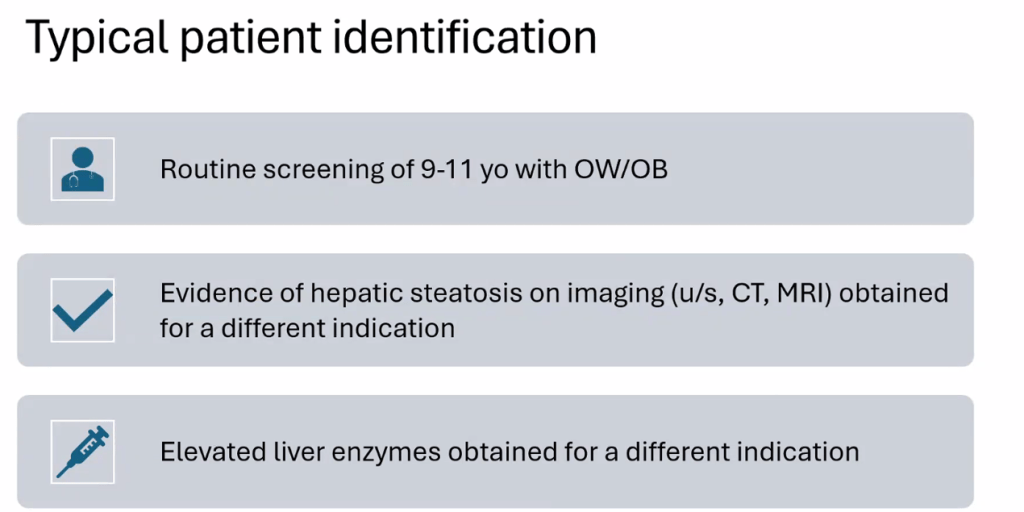

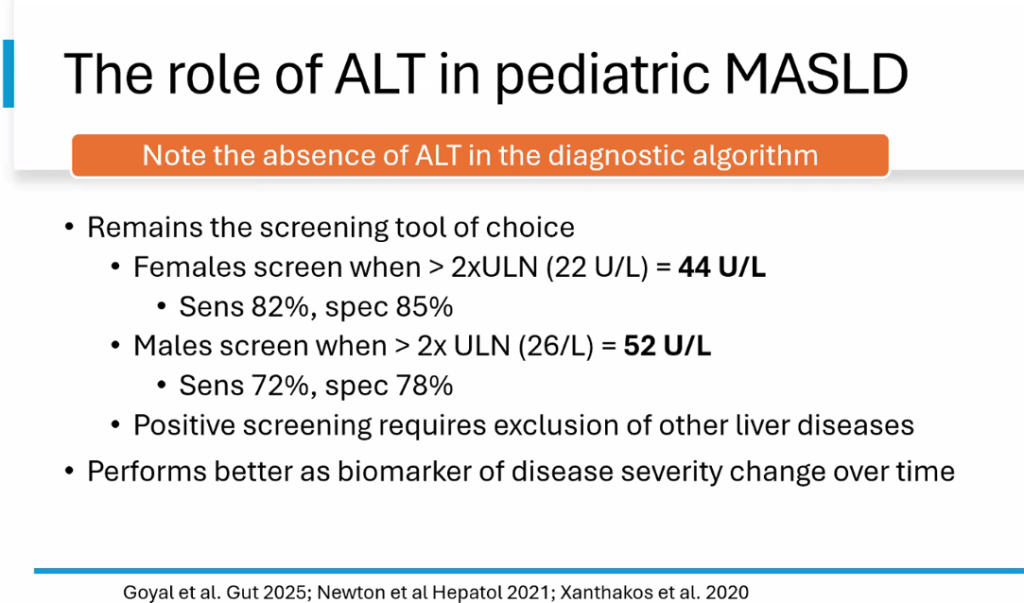

- ALT remains most common screening test with >26 U/L for adolescent males and >22 U/L for adolescent females having optimal sensitivity (>80-85%). We recommend “screen for MASLD in children aged 10 years or older with overweight and cardiometabolic risk factors or family history or obesity.” Annual screening recommended if at risk.

- Table 2 provides a long list of medications which may promote weight gain. These include antihistamines, steroids, some contraceptives, anticonvulsants, antidepressants, antipsychotics, methotrexate, and doxycycline

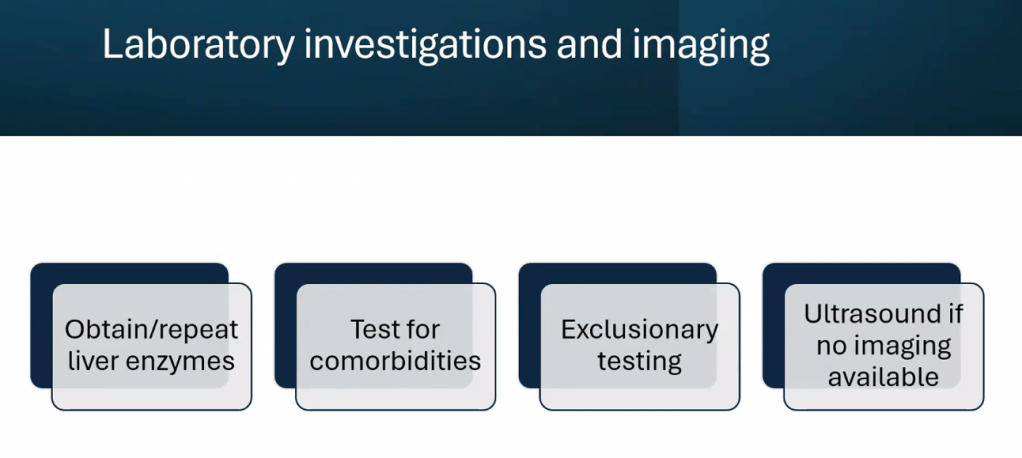

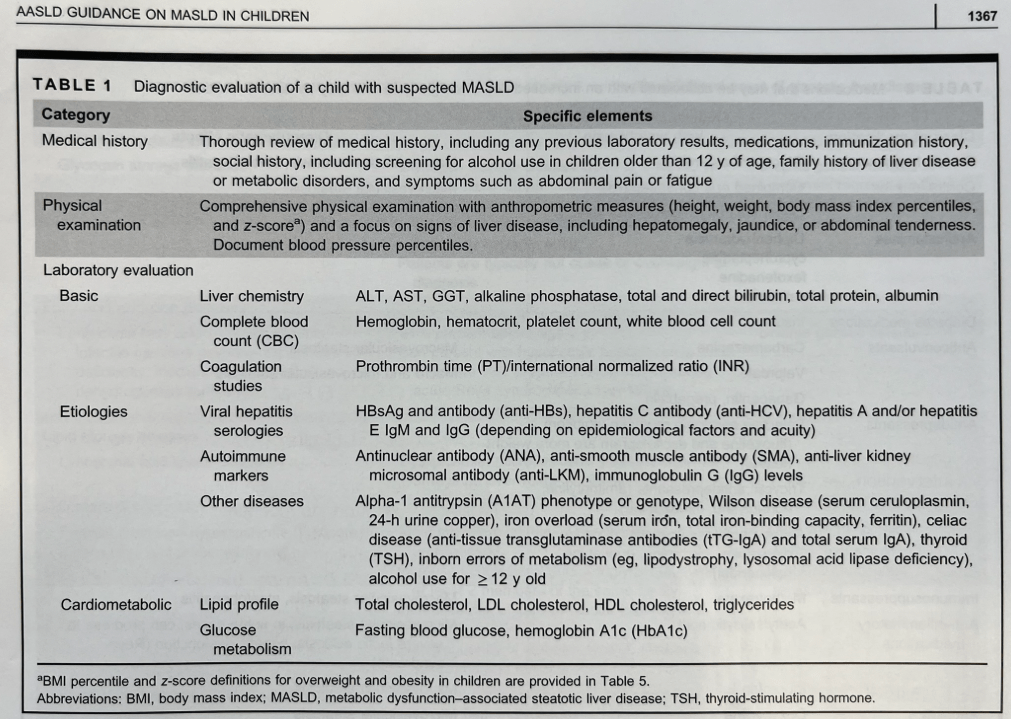

Diagnostic evaluation:

- Diagnosis of MASLD requires confirmation of steatosis (by imaging or biopsy) in addition to the presence of at least one cardiometabolic risk factor. ALT elevation with a cardiometabolic risk factor is insufficient.

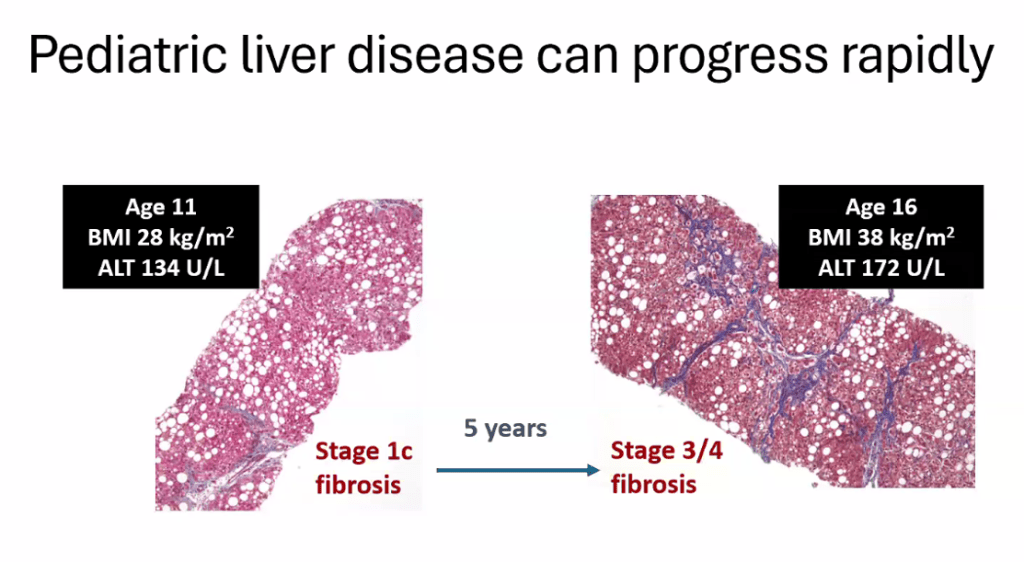

- “Consider liver biopsy in cases where there is uncertainty, especially if ALT levels are persistently elevated (>2 times the ULN)”

- Table 3 lists inborn errors of metabolism and monogenetic diseases which may cause childhood-onset steatotic liver disease. Evaluation of inborn errors of metabolism should be considered if atypical signs or symptoms, such as early onset (<3 yrs), rapidly progressive, absence of obesity, or other organ involvement (especially neurological)

- Table 4 summarizes imaging modalities to assess steatosis and fibrosis in children. Only MRI-PDFF has been validated in children (for steatosis)

- Table 5 describes BMI classification in children (WHO and AAP)

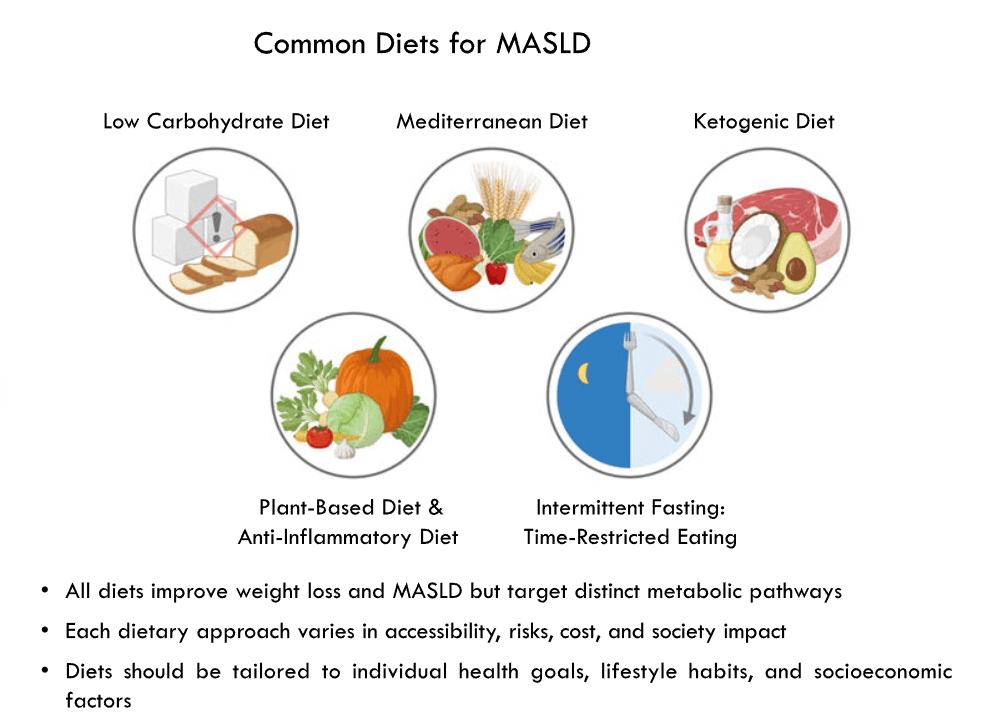

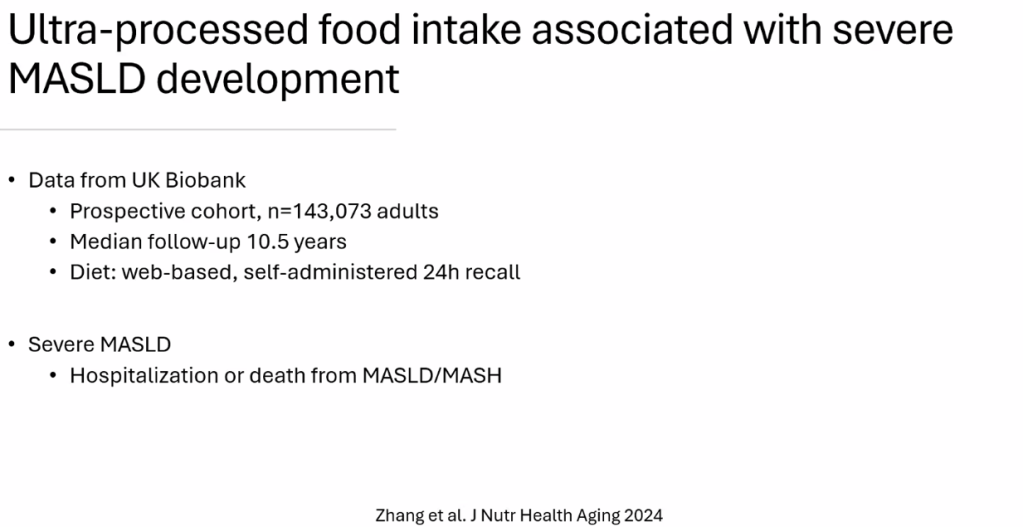

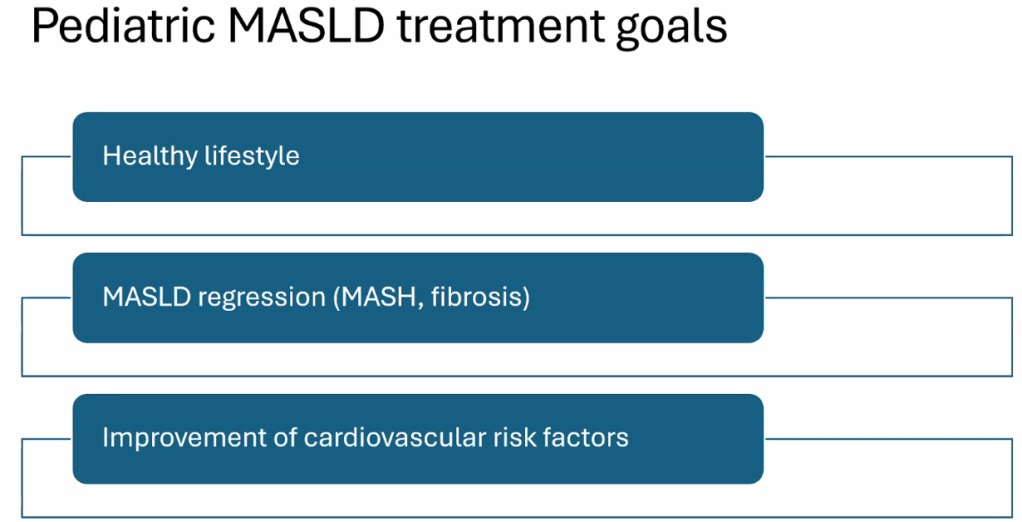

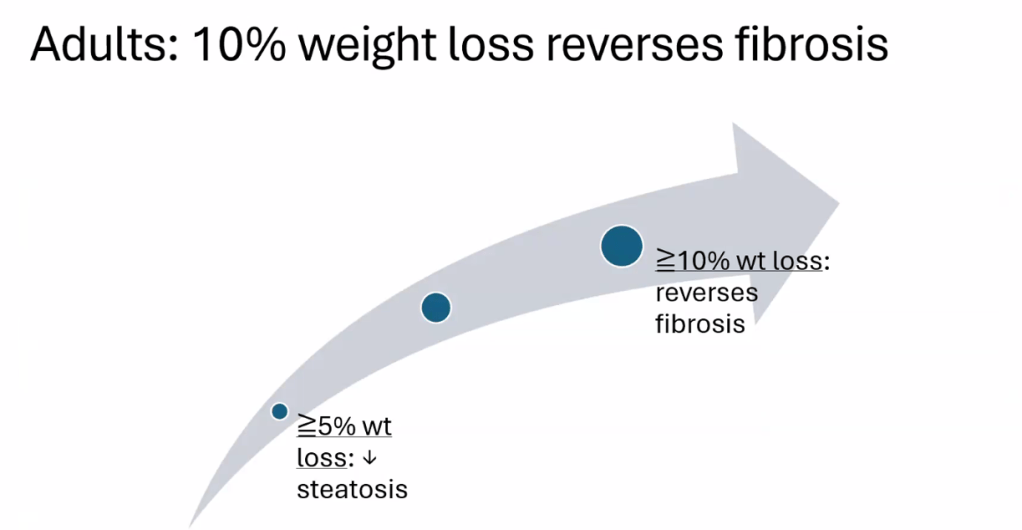

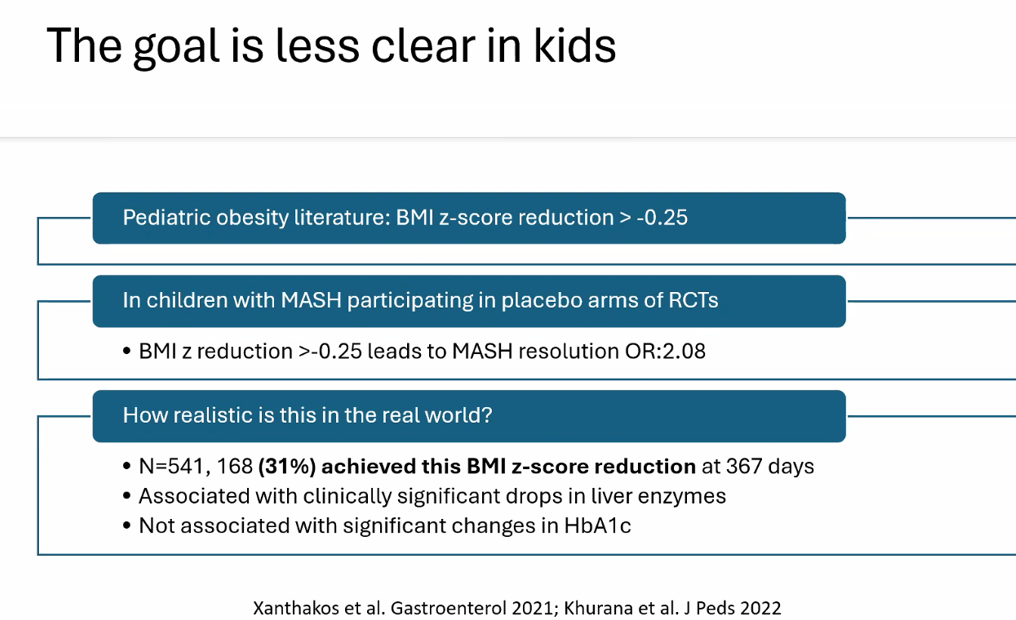

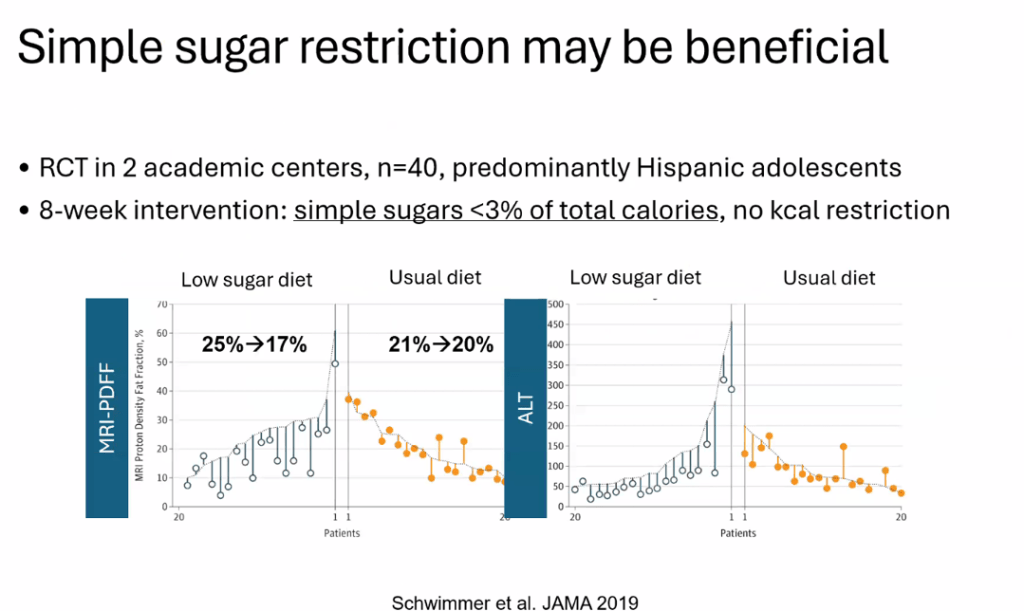

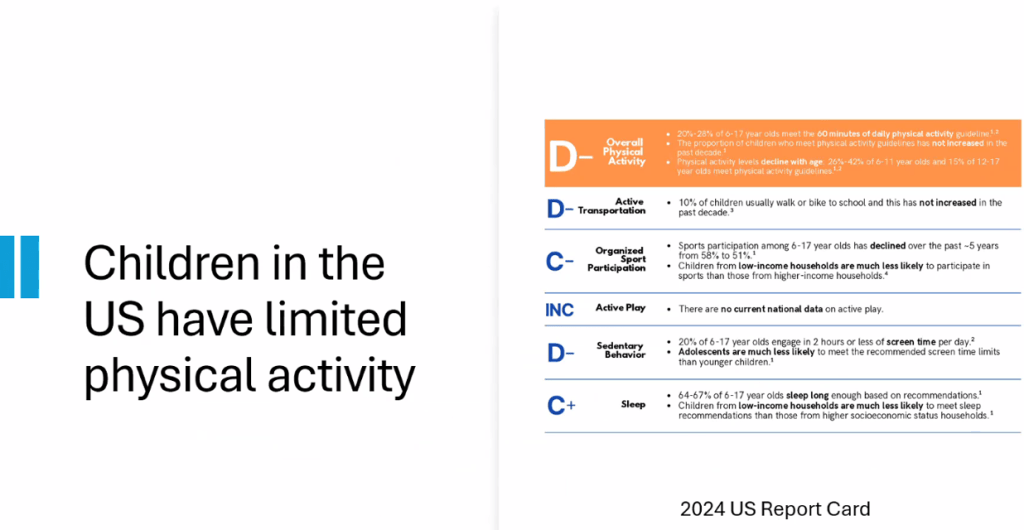

- Lifestyle treatments are detailed including diet (reduction of added sugars, Mediterranean diets) and exercise

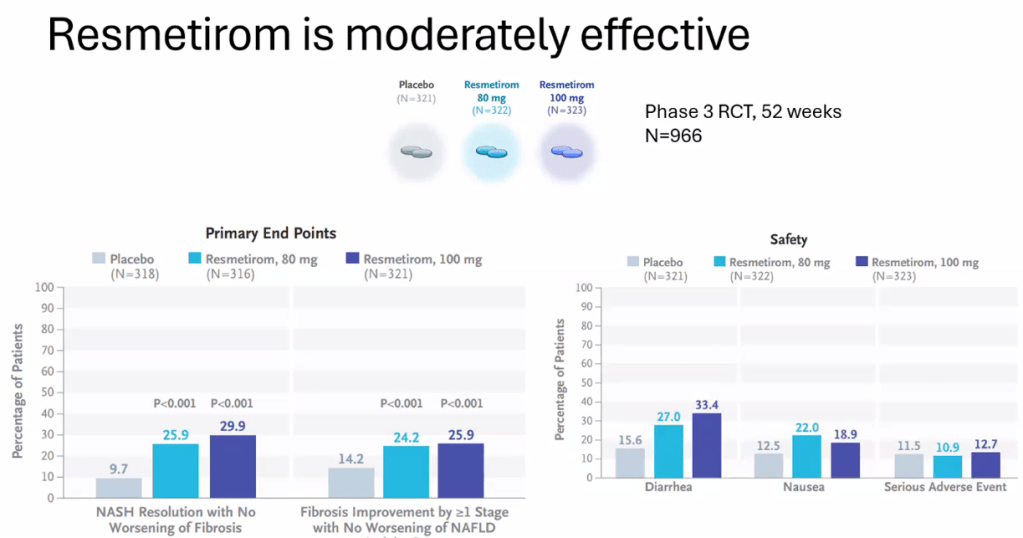

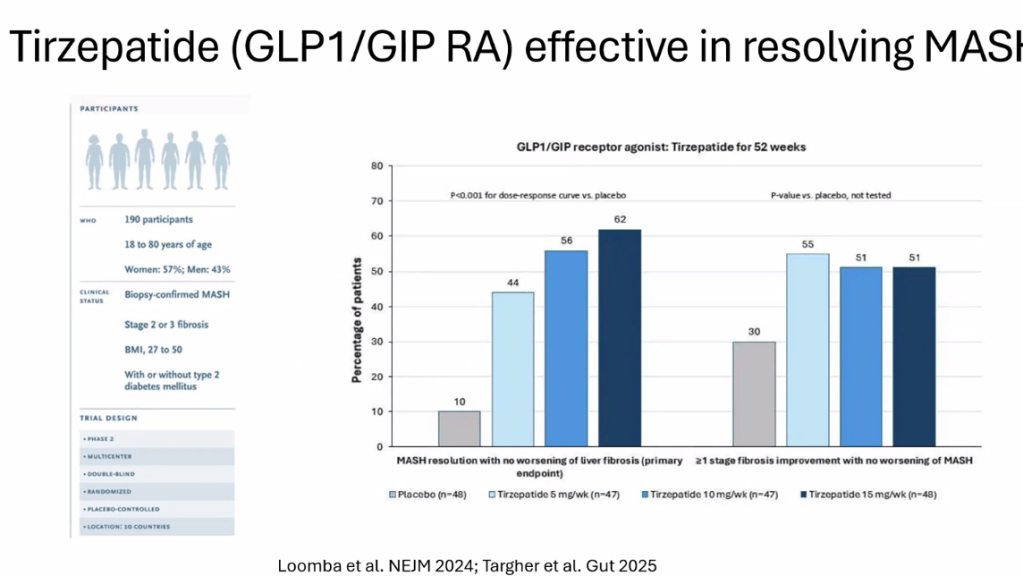

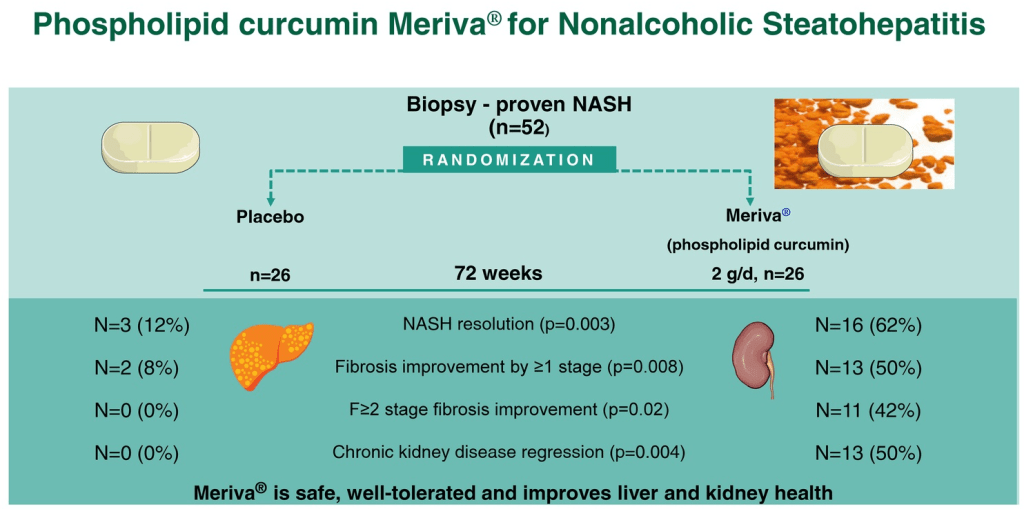

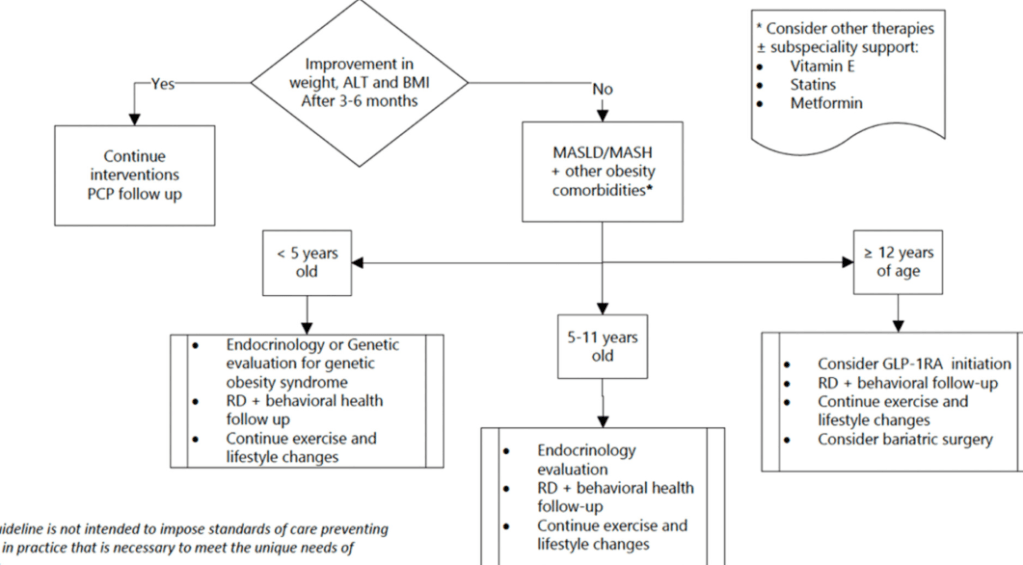

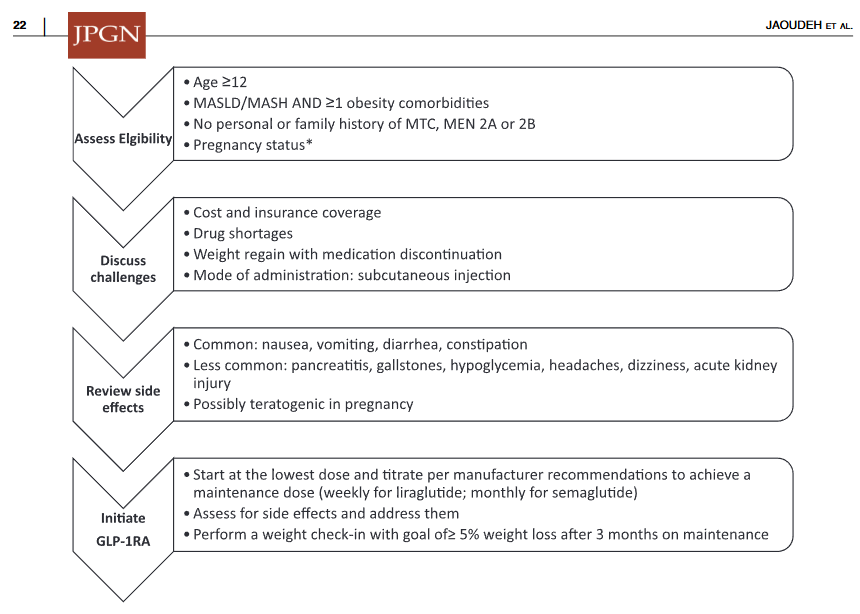

- Emerging medications are reviewed. However, practice statement notes “No pharmacotherapies are currently recommended or approved as specific treatments for MASLD or MASH in children…Medications approved for use in children ages 12 years and older to treat obesity or type 2 diabetes may be considered for children with MASLD.”

My take: This is a comprehensive practice guidance. It emphasizes an extensive diagnostic evaluation. The threshold for liver biopsy is relatively low in this guidance. As more data emerges, it is likely that more emphasis will be placed on the use of pharmacotherapies.

Related blog posts:

- Key Insights on MASLD from Dr. Marialena Mouzaki

- Clever Study: Hepatic Steatosis is Common in Overweight/Obese Children in First Four Years of Life

- Limitations of MRE and TE in Assessing Liver Fibrosis in Pediatric MASLD

- Diets for Obesity and Steatotic Liver Disease Plus Patient Information from FISPGHAN

- Forget the Surrogate Markers: Resolving MASH Improves Longevity Outcomes

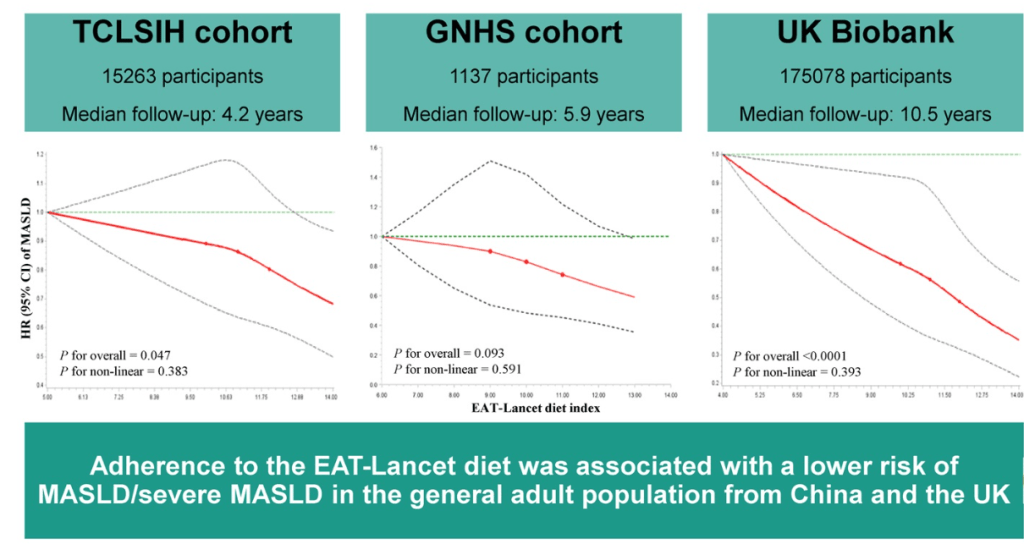

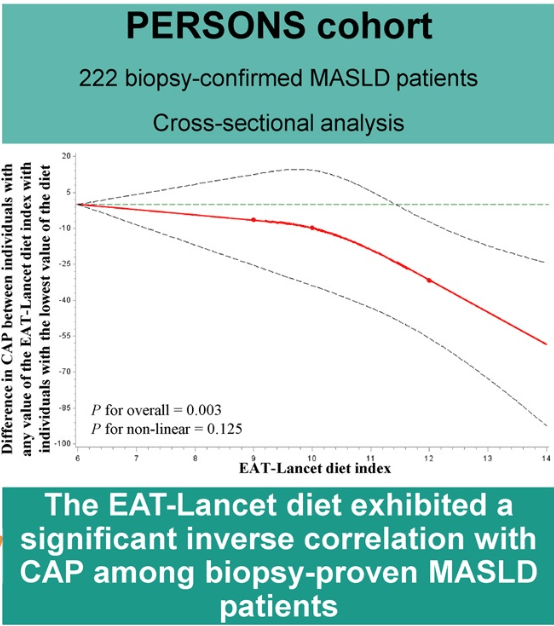

- EAT-Lancet Diet Associated with Reduced Risk of MASLD

- “You Can’t Outrun a Bad Diet”

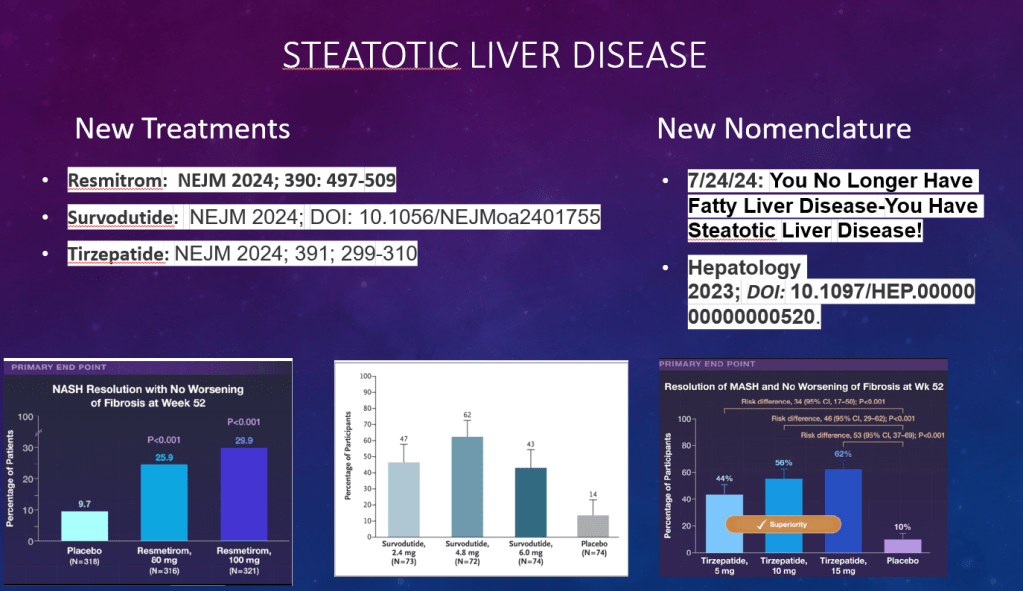

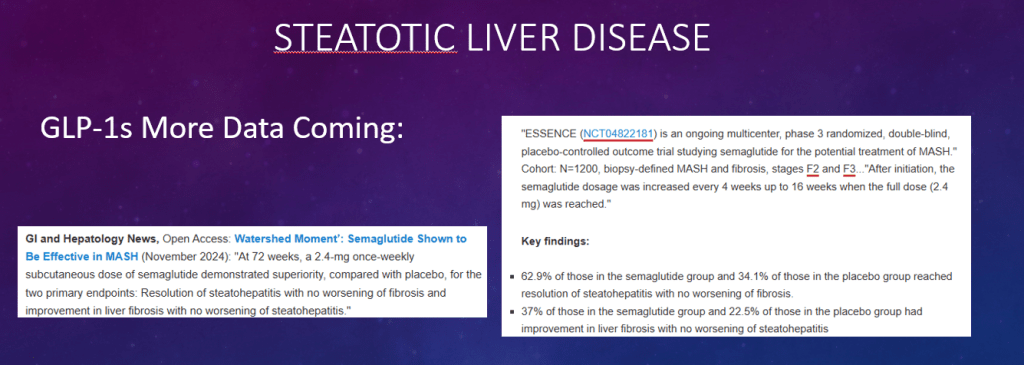

- Tirzepatide for Metabolic Dysfunction–Associated Steatohepatitis (MASH) & Uptick in GLP1 Use

- AASLD Practice Changes for Metabolic Liver Disease in 2024

- Bariatric Surgery Declines as GLP-1 Medications Rise

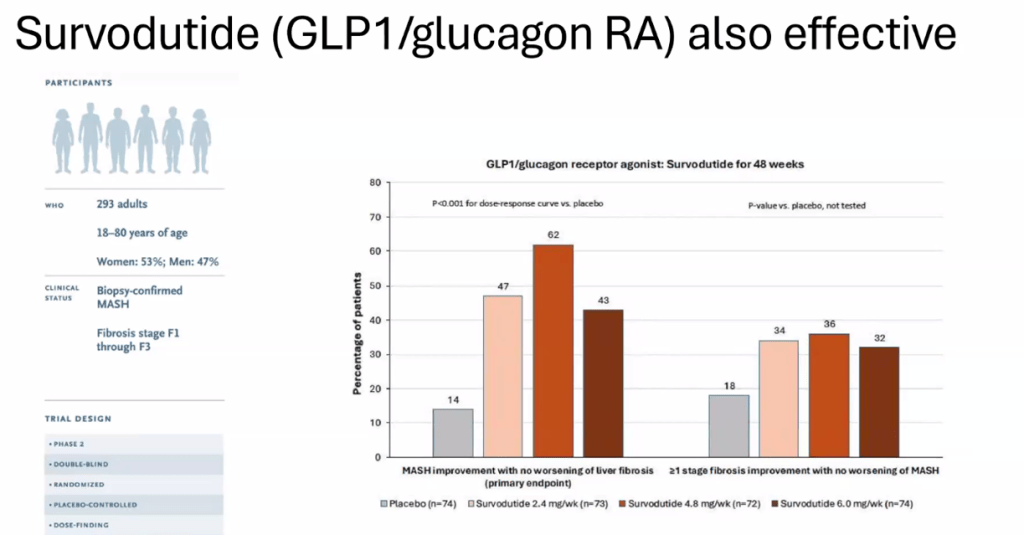

- Survodutide, Dual Glucagon Receptor/GLP-1 Receptor Agonist, for MASH (Phase II Trial)

- Resmetirom (Rezdiffra) -FDA Approved for MASH with Moderate to Advanced Fibrosis

- What’s More Important for Health: Exercise or Weight loss?

- Why Exercise is Good For Health

Disclaimer: This blog, gutsandgrowth, assumes no responsibility for any use or operation of any method, product, instruction, concept or idea contained in the material herein or for any injury or damage to persons or property (whether products liability, negligence or otherwise) resulting from such use or operation. These blog posts are for educational purposes only. Specific dosing of medications (along with potential adverse effects) should be confirmed by prescribing physician. Because of rapid advances in the medical sciences, the gutsandgrowth blog cautions that independent verification should be made of diagnosis and drug dosages. The reader is solely responsible for the conduct of any suggested test or procedure. This content is not a substitute for medical advice, diagnosis or treatment provided by a qualified healthcare provider. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a condition.