Y-C Ling et al. JPGN 2024;79:222–228. Performance of Baveno VII criteria for the screening of varices needing treatment in patients with biliary atresia

Methods: This retrospective study enrolled 48 BA patients (23 females and 25 males) who underwent an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) and transient elastography at a mean age of 11.18 ± 1.48 years. Transient elastography (Fibroscan® 502 Touch; Echosens) was applied for the LSM assessment in all BA patients recruited in this study.

Clinically-significant portal hypertension (CSPH) of Baveno VI criteria recommend avoiding upper endoscopies for cirrhotic patients with liver stiffness <20 kPa and platelets>150 × 10-9 cells/L (favorable Baveno VI status), and the CSPH of the expanded Baveno VI criteria as the exclusion of subjects with LSM < 25 kPa and platelet count >110 × 10-9 cells/L. (Ref: D Thabut et al. Gastroenterol 2019. Validation of Baveno VI Criteria for Screening and Surveillance of Esophageal Varices in Patients With Compensated Cirrhosis and a Sustained Response to Antiviral Therapy)

CSPH of Baveno VII criteria was defined as LSM ≥ 25 kPa and excluded patients with LSM < 15 kPa and platelet count ≥150 × 10-9 /L. Subjects with LSM between 20 and 25 kPa and platelets <150 × 10-9 /L or LSM between 15 and 20 kPa and platelets <110 × 10-9/L are also defined as CSPH. (Ref: Baveno VII criteria Ref: M Mendizabal et al. Annals of Hepatology; 2024: 29: 101180. Evolving portal hypertension through Baveno VII recommendations)

Key findings:

- The sensitivity and negative predictive value of Baveno VI and Baveno VII criteria for the prediction of varices needing treatment (VNT) in BA patients were both 100% and100%, respectively

In the discussion, the authors note that the utility of the Baveno VII criteria for adults. “The real‐world data showed the CSPH defined by Baveno VII criteria predicts a five‐times increase in the risk of liver decompensation in chronic active liver disease patients.”

My take: This study shows that the combination of LSM and platelet counts using the Baveno VI or VII criteria help select patients with BA who need upper endoscopy to screen for varices needing treatment. These criteria also identify patients needing liver transplantation.

Related blog posts:

- Time to Adjust the Knowledge Doubling Curve in Hepatology (2021) The 2nd guidance in this review discusses procedures for bleeding in patients with chronic liver disease. “For Platelets in the setting of cirrhosis: “Given the low risk of bleeding of many common procedures, potential risks of platelet transfusion, lack of evidence that elevating the platelet count reduces bleeding risk, and ability to use effective interventions, including transfusion and hemostasis if bleeding occurs, it is reasonable to perform both low‐ and high‐risk procedures without prophylactically correcting the platelet count...An individualized approach to patients with severe thrombocytopenia before procedures is recommended.” And, ““The INR should not be used to gauge procedural bleeding risk in patients with cirrhosis who are not taking vitamin K antagonists (VKAs)…Measures aimed at reducing the INR are not recommended before procedures in patients with cirrhosis who are not taking VKAs…FFP transfusion before procedures is associated with risks and no proven benefits.”

- Transient Elastography in Pediatric Liver Disease

- #NASPGHAN19 Liver Symposium (Part 3)

- “White Nipple Sign” (aka Mount St. Helens’ sign) and Varices

- New Paradigm in Treating Varices and Cirrhosis Management (in Adults)

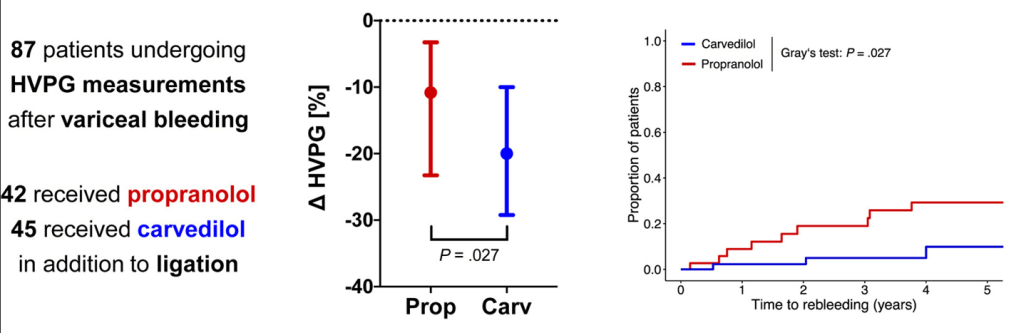

- Why Carvedilol Is Considered Best Pharmaceutical Agent to Prevent Variceal Bleeding (in Adults)

Disclaimer: This blog, gutsandgrowth, assumes no responsibility for any use or operation of any method, product, instruction, concept or idea contained in the material herein or for any injury or damage to persons or property (whether products liability, negligence or otherwise) resulting from such use or operation. These blog posts are for educational purposes only. Specific dosing of medications (along with potential adverse effects) should be confirmed by prescribing physician. Because of rapid advances in the medical sciences, the gutsandgrowth blog cautions that independent verification should be made of diagnosis and drug dosages. The reader is solely responsible for the conduct of any suggested test or procedure. This content is not a substitute for medical advice, diagnosis or treatment provided by a qualified healthcare provider. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a condition.