12/7/23 NASPGHAN Alert: Guidance for Flovent HFA Upcoming Discontinuation Used For The Treatment of Eosinophilic Esophagitis

Situation:

Brand name Flovent HFA will no longer be manufactured after December 31, 2023.

Background:

• Flovent HFA is a commonly utilized swallowed topical steroid treatment for patients with eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE). It works by the patient swallowing the aerosolized medication dispensed by a metered dose inhaler (MDI).

• Both Medicaid and many private insurance formularies have transitioned to breath-actuated inhalers as their preferred inhaled steroid formulation, which cannot be used for EoE because they cannot be swallowed.

• GlaxoSmithKline will be discontinuing manufacture of brand Flovent HFA after December 31, 2023. While an authorized generic fluticasone HFA is available, it is not listed on many insurance formularies and for those that do include it, it is typically not listed as a preferred medication.

• Two other steroid MDIs are available on the market – Alvesco HFA (ciclesonide) and Asmanex HFA (mometasone). Limited data is available regarding dosing and efficacy in EoE 1,2.

• We are actively working to raise these concerns with major payors.

Assessment & Recommendation:

Given upcoming Flovent HFA discontinuation, patients needing this formulation of drug could be switched to generic fluticasone HFA. For many insurances this may require a prior authorization, which may delay initiation of the medication and families should be counselled accordingly.

In those whom generic fluticasone HFA is denied despite submission of a prior authorization, alternative options include:

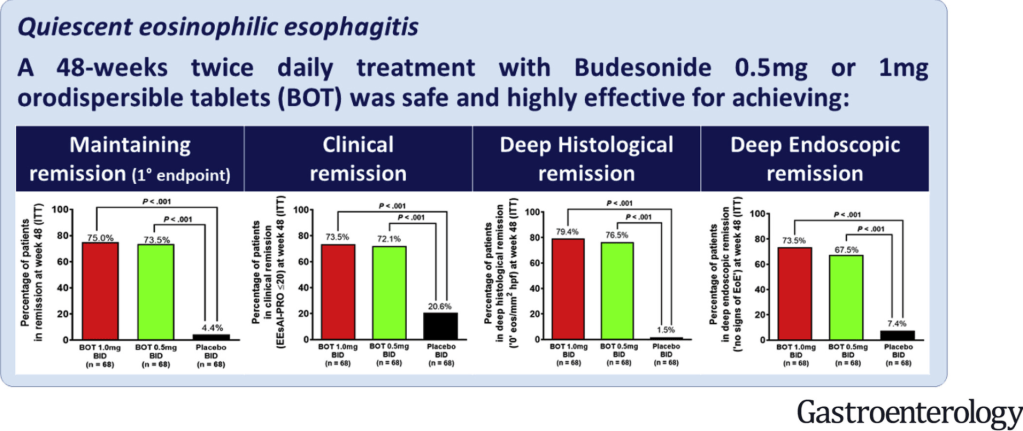

• Oral viscous budesonide

• Swallowed topical Asmanex (mometasone) HFA or Alvesco (ciclesonide) HFA. Data on dosing in EoE is limited and these medications are also likely to require a PA.

References:

1. Tytor J, Larsson H, Bove M, Johansson L, Bergquist H. Topically applied mometasone furoate improves dysphagia in adult eosinophilic esophagitis – results from a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2021 Jun;56(6):629-634. doi: 10.1080/00365521.2021.1906314. Epub 2021 Apr 8. PMID: 33831327.

2. Nistel M, Nguyen N, Atkins D, Miyazawa H, Burger C, Furuta GT, Menard-Katcher C. Ciclesonide Impacts Clinicopathological Features of Eosinophilic Esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021 Nov;9(11):4069-4074. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2021.06.058. Epub 2021 Jul 19. PMID: 34293498.

The information provided is intended solely for educational purposes and not as medical advice. It is not a substitute for care by a trained medical provider. NASPGHAN does not endorse any of these products and is not responsible for any omissions. For additional information please email floventquestions@naspghan.org.

Any substitution should only be done under the recommendation and supervision of a healthcare professional.