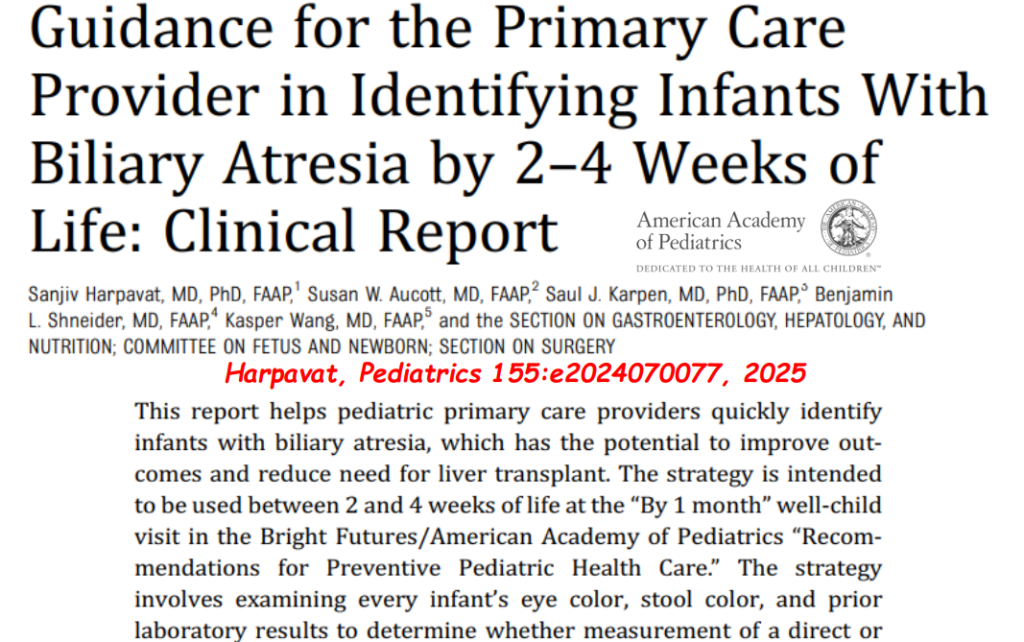

AM Upton et al. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2025;81:212–216. The “maximum echogenicity” at the right portal vein: Biliary atresia versus Alagille syndrome

See related ultrasound study from last week: Improving Ultrasound Examination to Identify Biliary Atresia

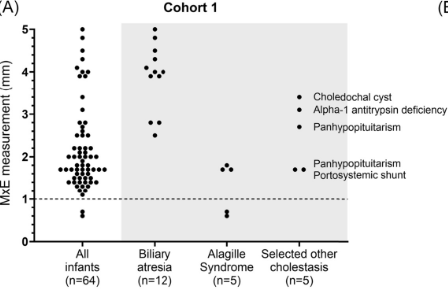

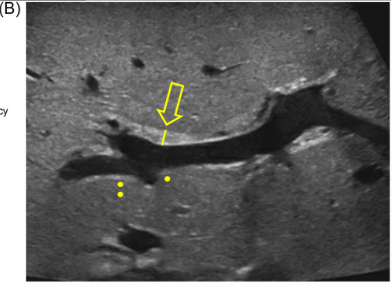

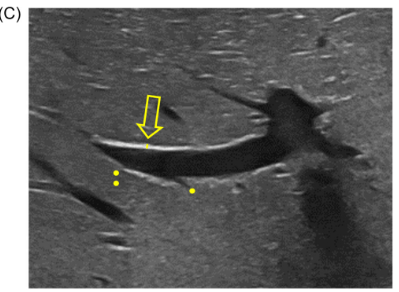

Background/Methods: One way clinicians can distinguish between biliary atresia and Alagille syndrome is with a positive “triangular cord sign.” This ultrasound finding refers to a thickened echogenicity at the anterior aspect of the right portal vein…the maximum echogenicity at the anterior aspect of the right portal vein (“maximum echogenicity” or “MxE”) was measured in a group of infants with cholestasis (Cohort 1, n=64) and in another group of infants with Alagille syndrome (Cohort 2, n=30).

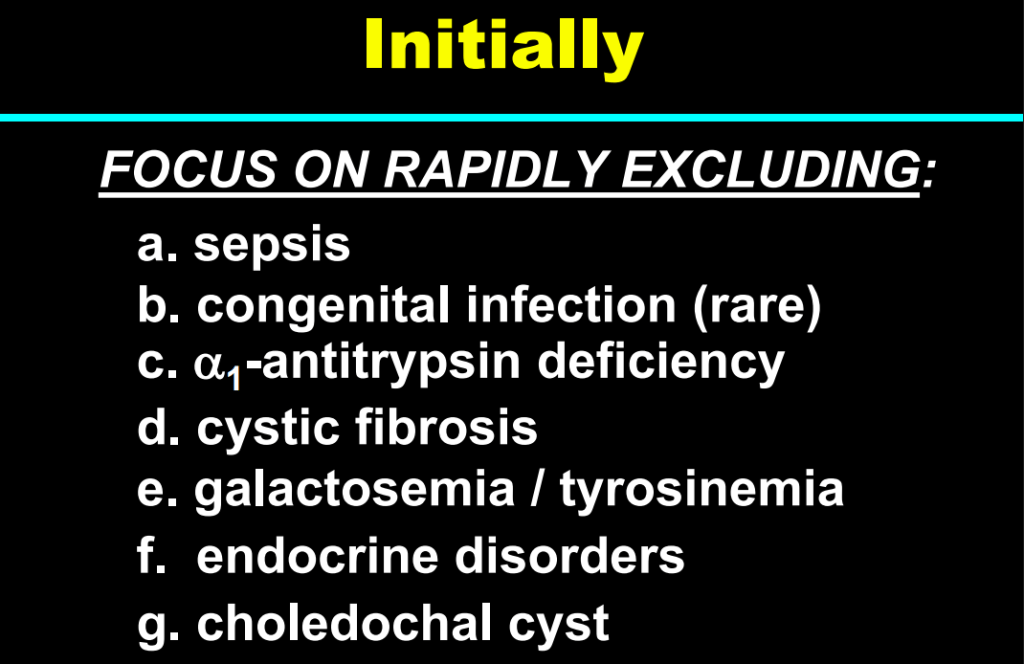

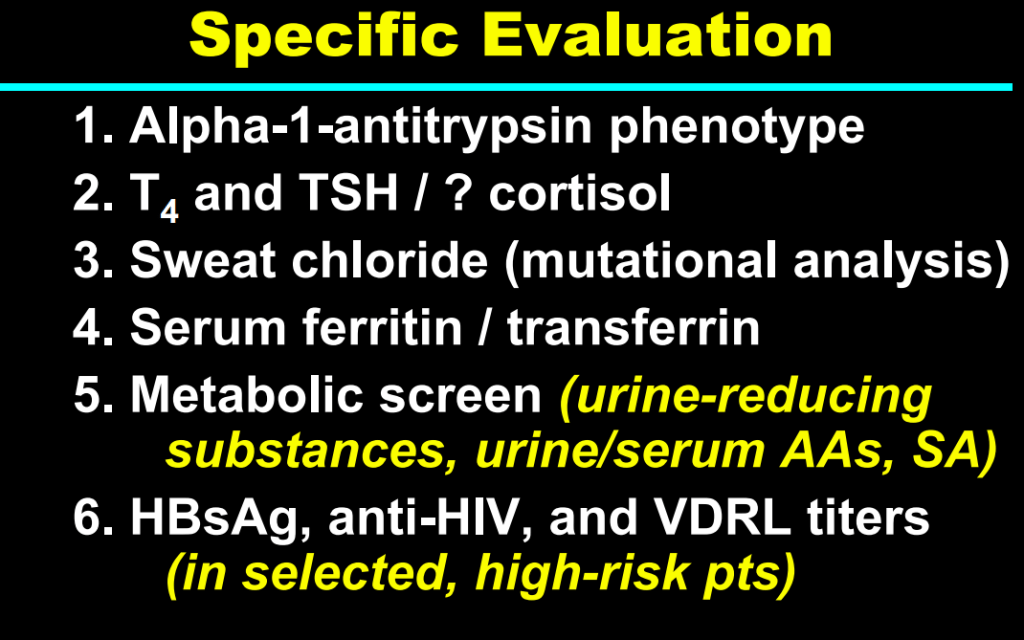

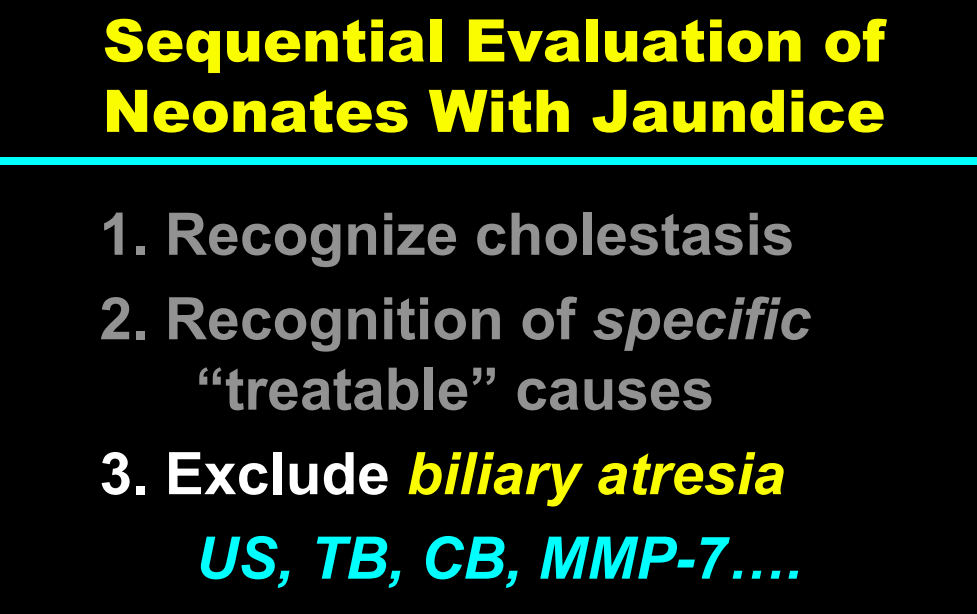

Key findings:

- “Thin echogenicity at the anterior aspect of the right portal vein may help distinguish between biliary atresia and Alagille syndrome…None of the 12 infants with biliary atresia in Cohort 1 had a MxE < 1.0 mm”

- “A MxE < 1.0 mm could help identify Alagille syndrome. 2 of the 64 infants with cholestasis in Cohort 1 had a MxE < 1.0 mm. Both infants were eventually diagnosed with Alagille syndrome. In the Cohort 2 infants with Alagille syndrome, 16 of 30 infants had a MxE < 1.0 mm”

Discussion Point:

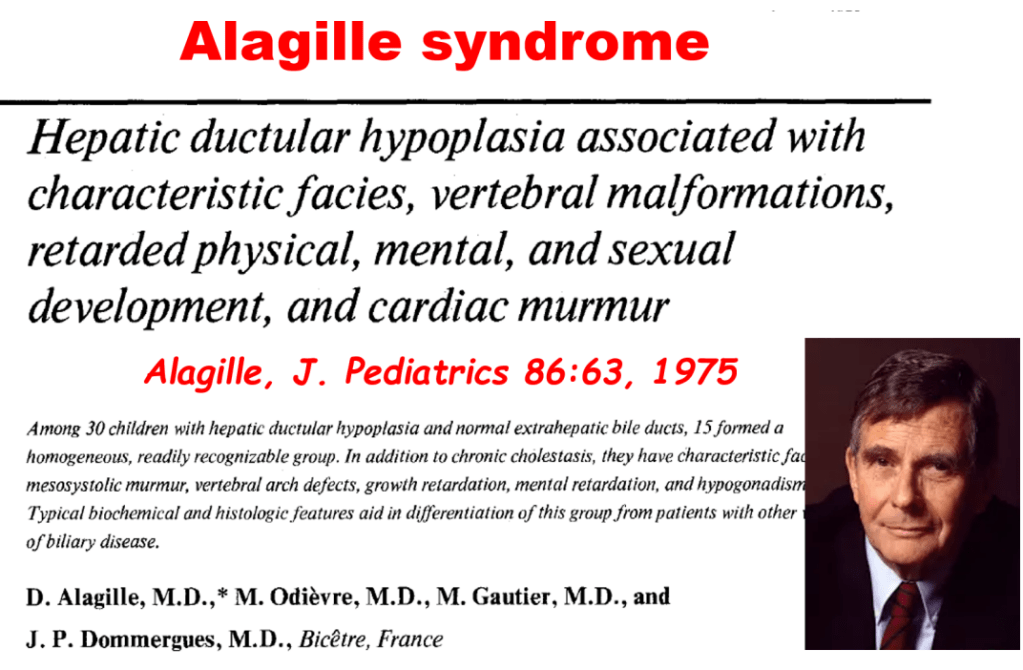

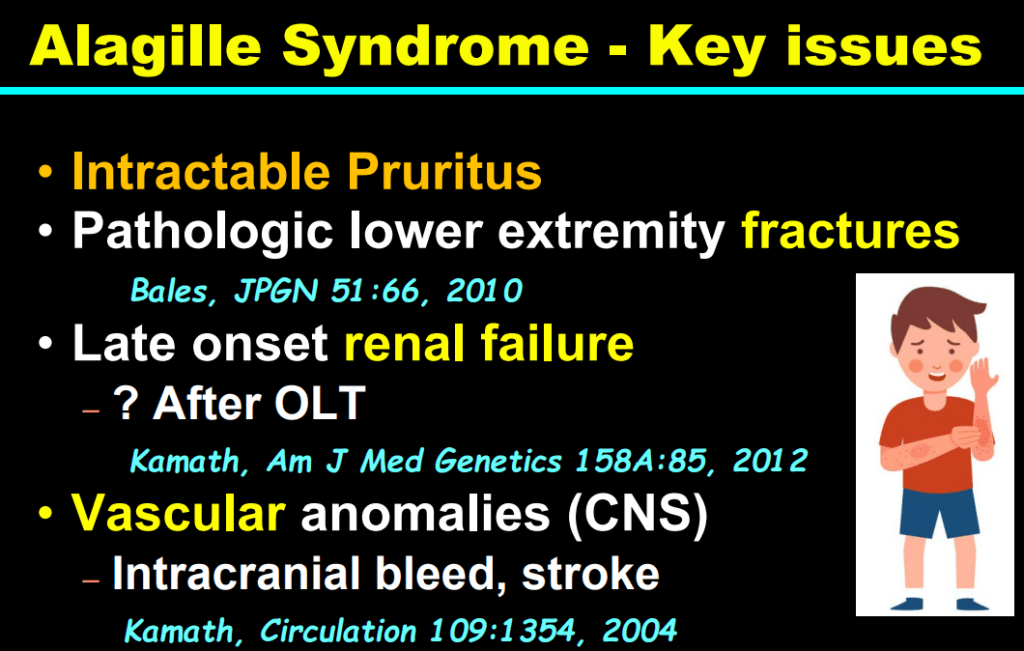

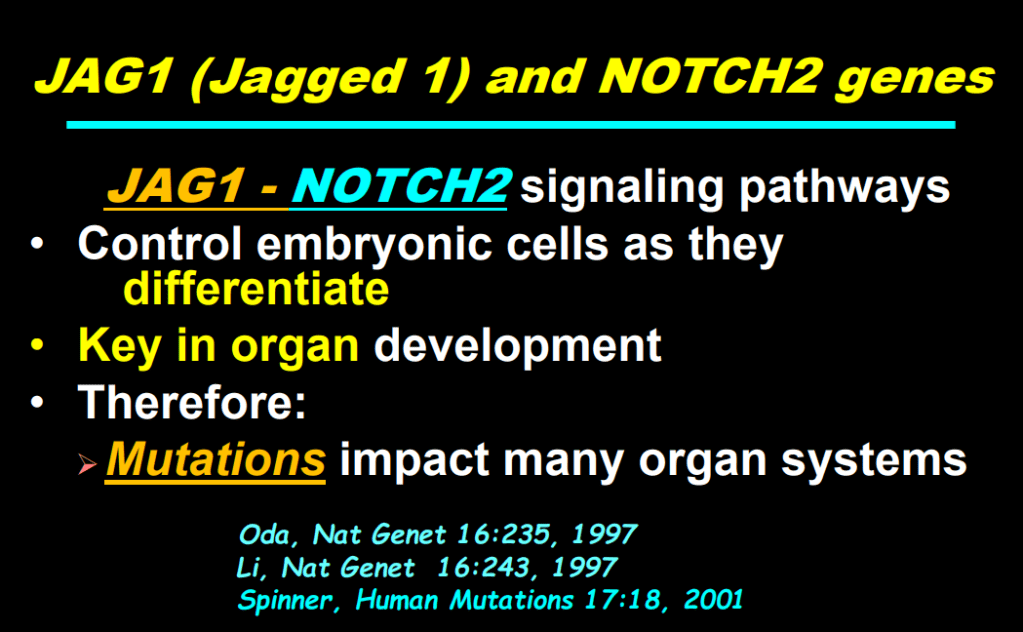

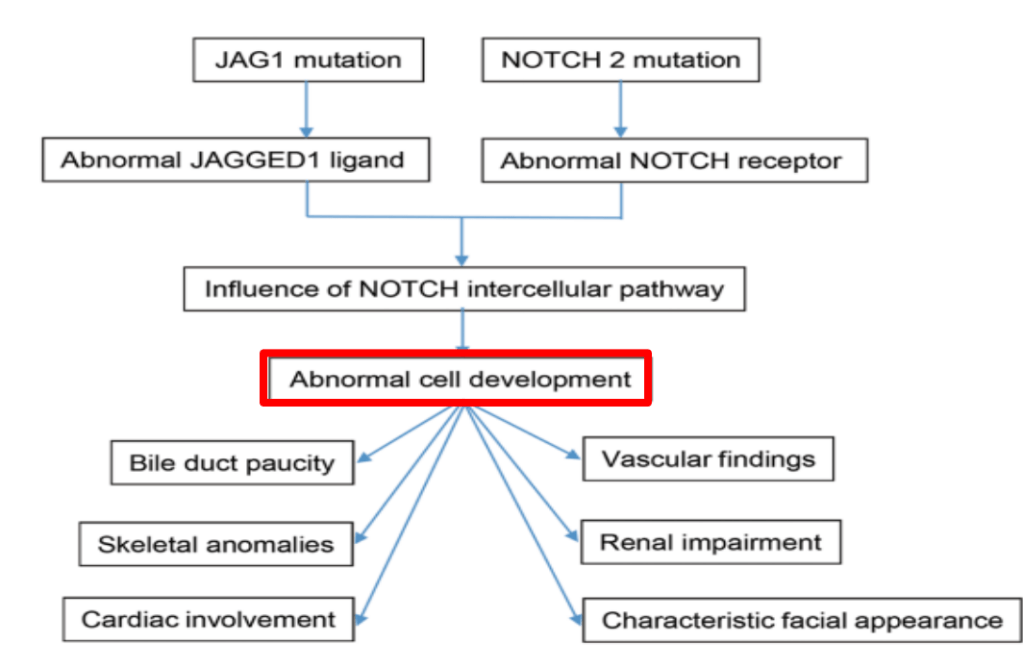

“Infants with Alagille syndrome can have smaller bile ducts which may be inapparent on invasive testing such as cholangiography. As a result, they may be presumptively diagnosed with biliary atresia and inappropriately treated with the Kasai portoenterostomy. Unfortunately, these infants have poorer outcomes compared to infants with Alagille syndrome who do not receive the Kasai portoenterostomy.” Thus, distinguishing Alagille from biliary atresia is very important.

My take: This study shows that MxE (a refinement of what has previously been called the triangular cord sign) on ultrasound may help distinguish biliary atresia from Alagille syndrome. As this is a single-center study, it will be important to determine if this ultrasound finding can be replicated in other centers and whether the finding is operator-dependent.

Related blog posts:

- Improving Ultrasound Examination to Identify Biliary Atresia

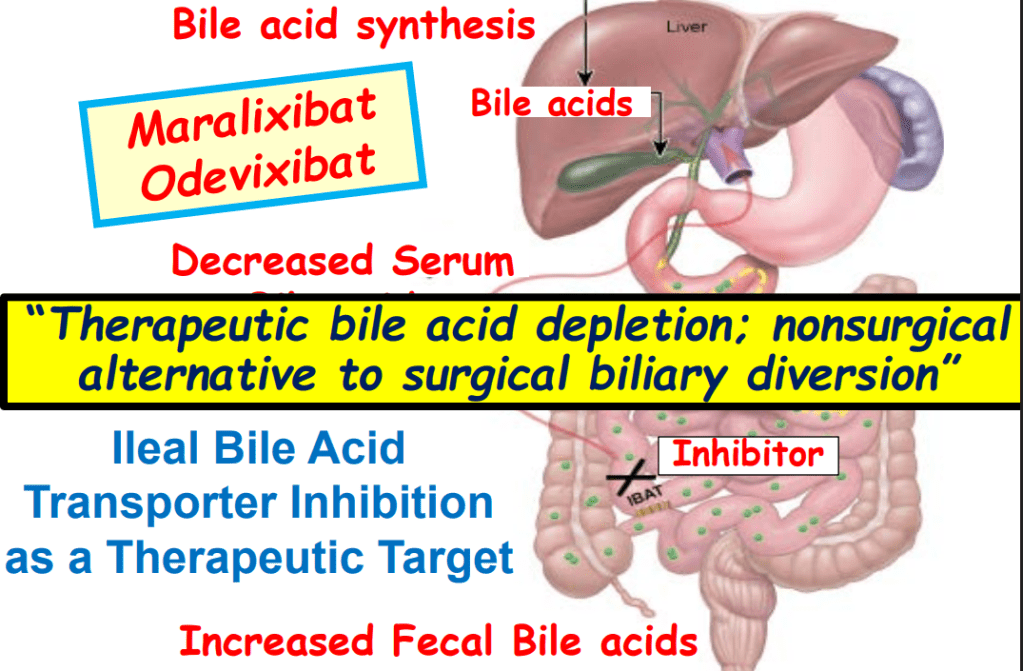

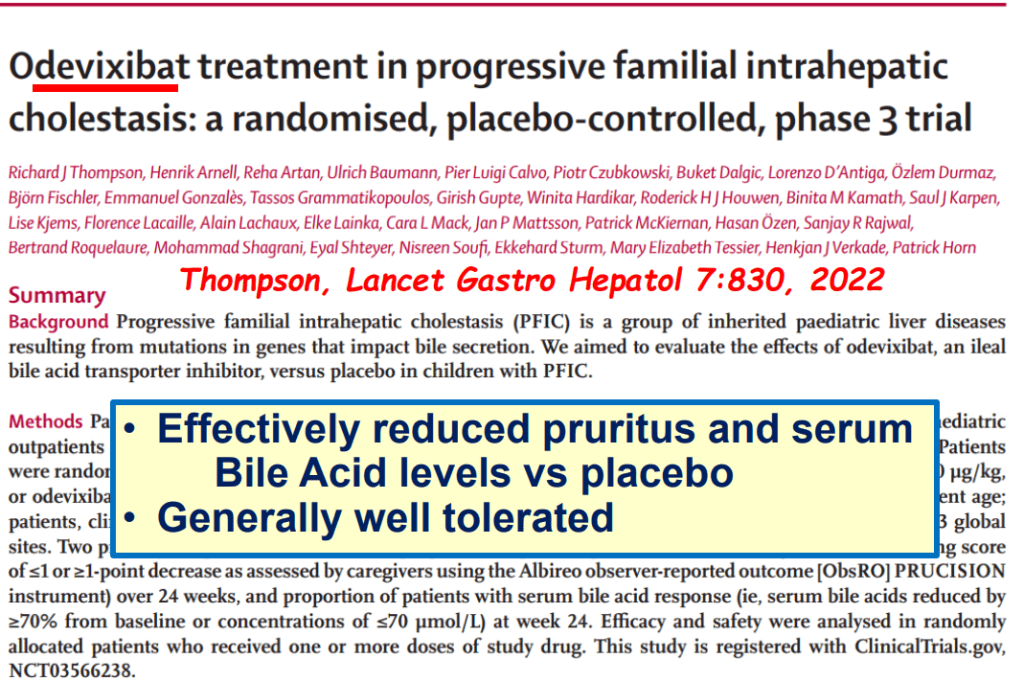

- Efficacy and Safety of Odevixibat with Alagille Syndrome (ASSERT Trial)

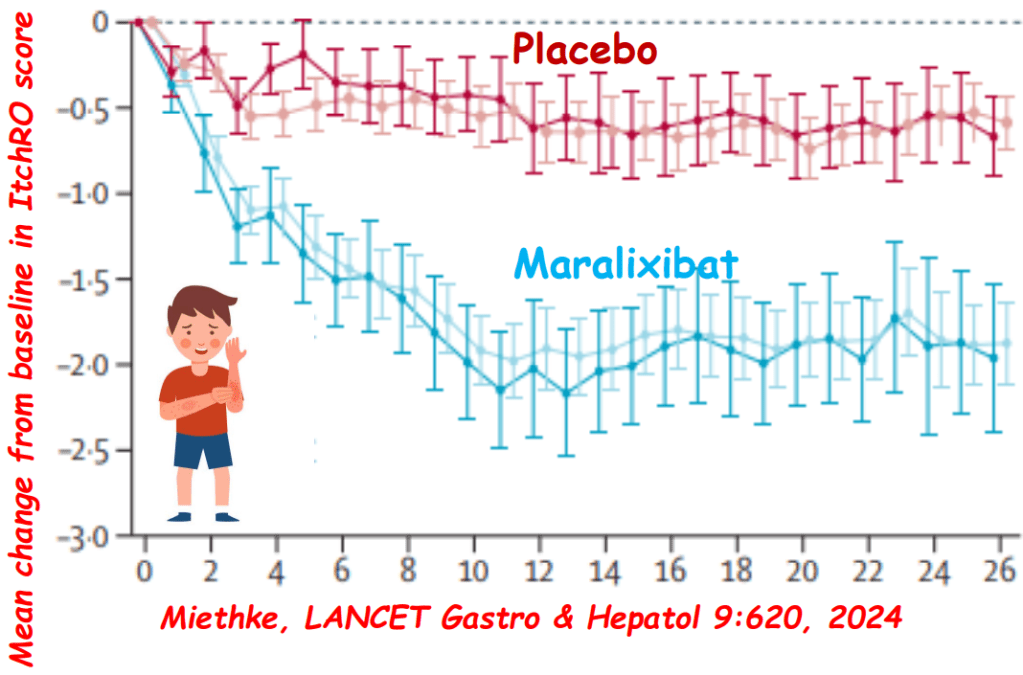

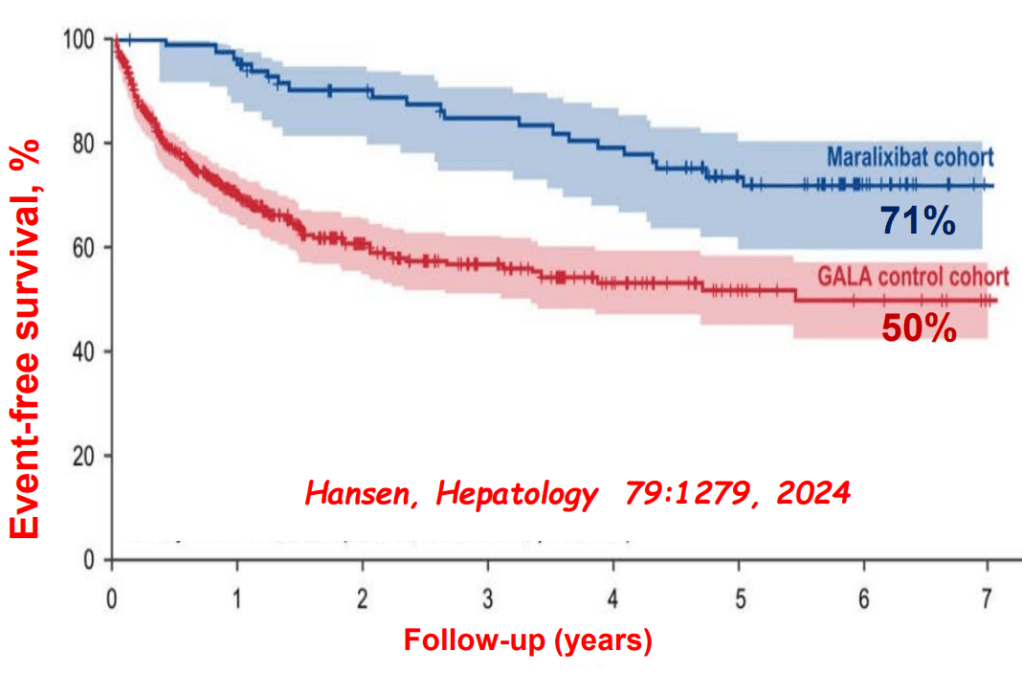

- Relooking at 6-Year Data of Maralixibat for Alagille Syndrome

- GALA: Alagille Study

- NASPGHAN Alagille Syndrome Webinar

Disclaimer: This blog, gutsandgrowth, assumes no responsibility for any use or operation of any method, product, instruction, concept or idea contained in the material herein or for any injury or damage to persons or property (whether products liability, negligence or otherwise) resulting from such use or operation. These blog posts are for educational purposes only. Specific dosing of medications (along with potential adverse effects) should be confirmed by prescribing physician. Because of rapid advances in the medical sciences, the gutsandgrowth blog cautions that independent verification should be made of diagnosis and drug dosages. The reader is solely responsible for the conduct of any suggested test or procedure. This content is not a substitute for medical advice, diagnosis or treatment provided by a qualified healthcare provider. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a condition