M Mostavi, S Lee, V Martin. JPGN Reports. 2026;7:55–58. When manual disimpaction isn’t enough: Case report and review of neostigmine’s role in refractory constipation management

This was a case report of a 21 yo with chronic constipation and likely undiagnosed autism spectrum disorder hospitalized for severe fecal retention, unresponsive to nasogastric polyethylene glycol. He underwent a manual disimpaction but due to residual stool in more proximal colon, Neostigmine was administered with good results.

Methods: “The patient underwent manual disimpaction under general anesthesia with a large amount of hard stool removed from the rectum. He was noted to have ongoing abdominal distension with significant palpable stool more proximally. A trial of 1 mg intravenous (IV) neostigmine was given. This was done without anticholinergic co-administration due to his persistent tachycardia (HR ~ 120 s) and with close heart rate monitoring. Passive passage of stool occurred within 5 min of drug administration. Subsequently, neostigmine was titrated in additional 1 mg IV doses every 3–5 min. His heart rate remained above 90bpm. He received a total of four doses of neostigmine over 20 min. Each administration, combined with abdominal massage, produced large amounts of soft stool along with marked reduction in distension and palpable stool burden.

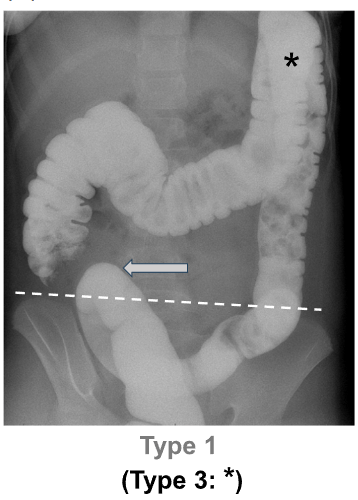

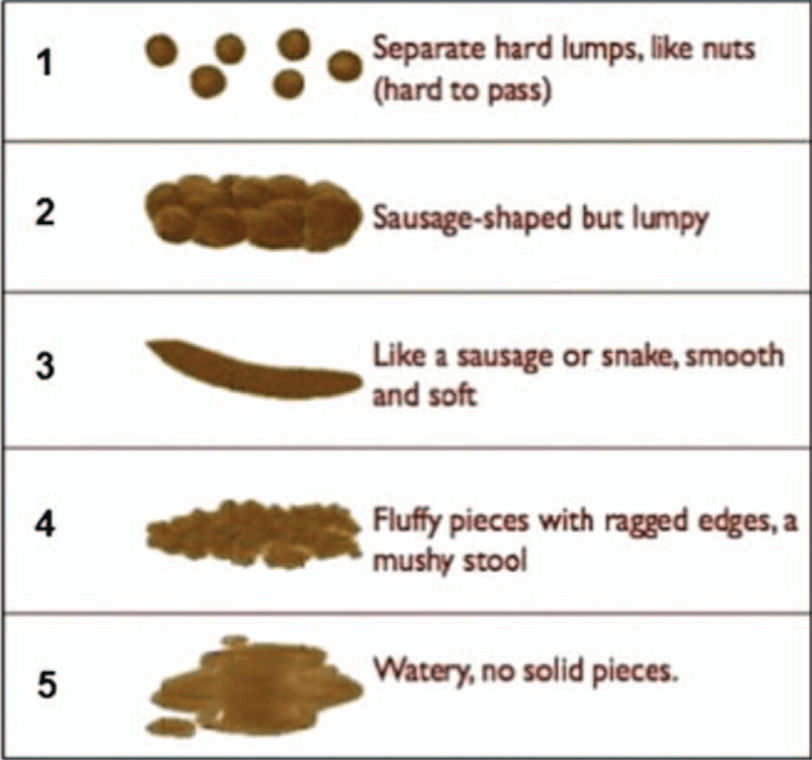

Before NG cleanout and disimpaction:

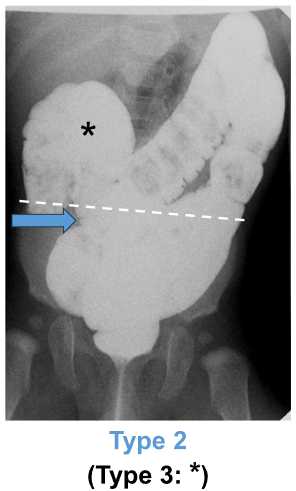

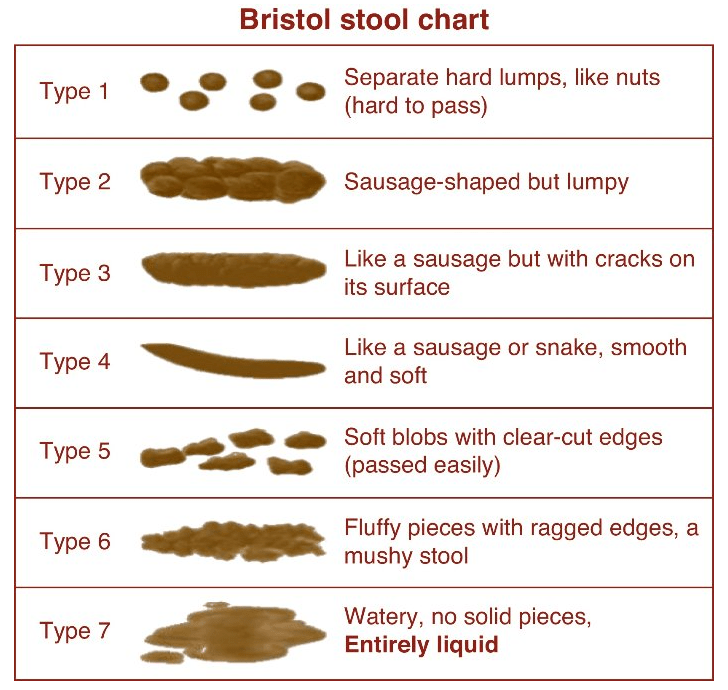

After NG cleanout and disimpaction/Neostigmine:

Pharmacokinetics:

” Neostigmine has been clinically utilized by anesthesiologists to reverse the effects of non-depolarizing neuromuscular blocking agents…In the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, the accumulation of acetylcholine in the neuromuscular junction of the small intestine and colon results in increased contractility and peristalsis, thus promoting defecation. Neostigmine is predominately administered intravenously with typical dose ranges from 0.03 to 0.07 mg/kg, up to maximum 5 mg. The peak effect typically occurs between 7 and 10 min, while the duration of action lasts approximately 55–75 min in adult patients…

Because of its cholinergic effects on the muscarinic receptors of the cardiac parasympathetic nervous system, neostigmine results in a significant decrease in heart rate. Therefore, when neostigmine is bolused to reverse non-depolarizing paralytics at the clinically appropriate dose (~3–5 mg IV), it is always co-administered with glycopyrrolate or atropine to prevent bradycardia at a 1:1 volume ratio.”

My take (borrowed from authors): “This case demonstrates that intravenous neostigmine can be a safe and effective adjunct to manual disimpaction in severe refractory constipation when administered in a monitored setting.”

Related blog posts:

- Soap Suds Enemas & ED Management of Impactions

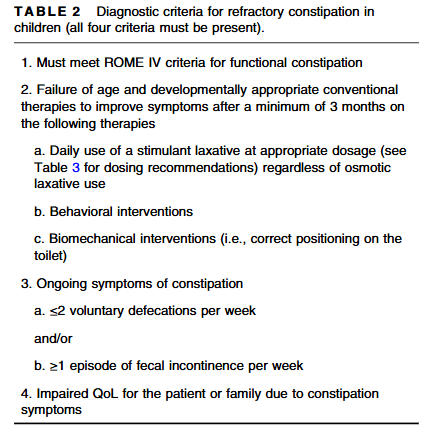

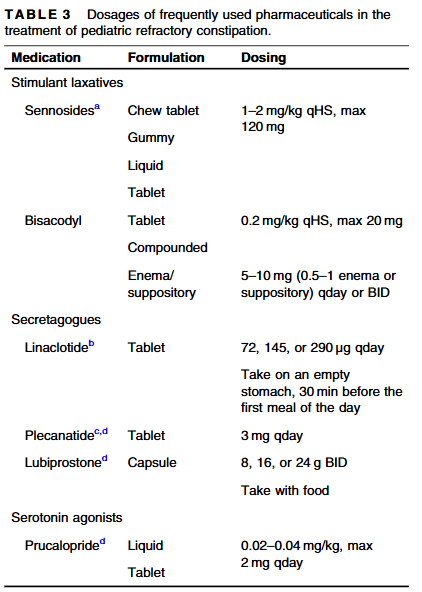

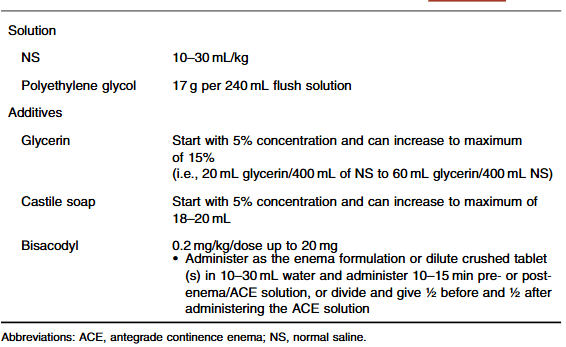

- Position Paper: Pediatric Refractory Constipation Management

- “Waste” of a CT Scan

- Stercoral Colitis

- Safety of Senna-Based Laxatives

- Constipation Action Plan: Better Instructions, Fewer Phone Calls

- Does It Make Sense to Look for Celiac Disease in Children with Functional Constipation?

- You Can Do Anorectal Manometry in Your Sleep, But Should You?

- More than Two Years of Constipation Before Specialty Help

Disclaimer: This blog, gutsandgrowth, assumes no responsibility for any use or operation of any method, product, instruction, concept or idea contained in the material herein or for any injury or damage to persons or property (whether products liability, negligence or otherwise) resulting from such use or operation. These blog posts are for educational purposes only. Specific dosing of medications (along with potential adverse effects) should be confirmed by prescribing physician. Because of rapid advances in the medical sciences, the gutsandgrowth blog cautions that independent verification should be made of diagnosis and drug dosages. The reader is solely responsible for the conduct of any suggested test or procedure. This content is not a substitute for medical advice, diagnosis or treatment provided by a qualified healthcare provider. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a condition.