G Bora et al. JPGN Reports. 2026;7:1–5. Open Access! Maralixibat for the treatment of severe xanthomas in two children with Alagille syndrome: Case reports

Key findings:

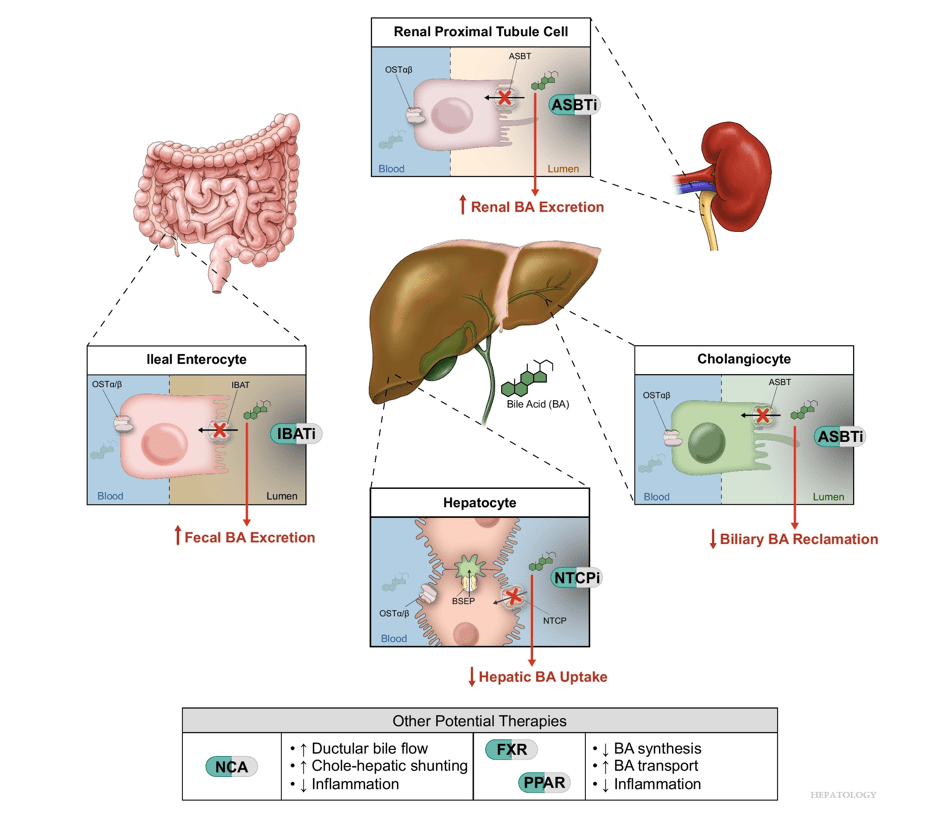

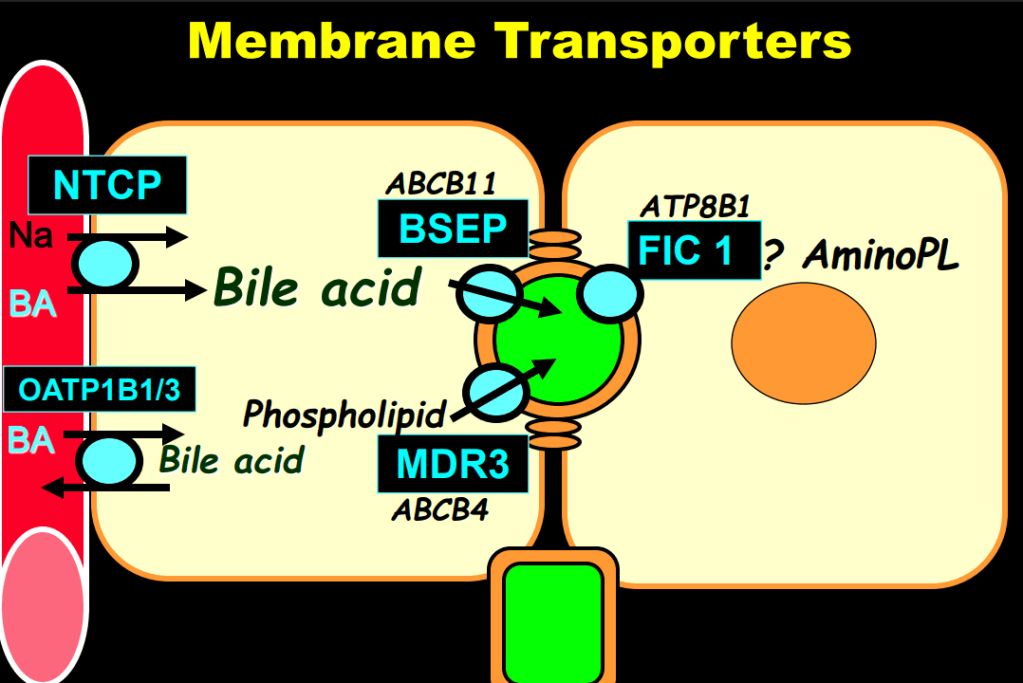

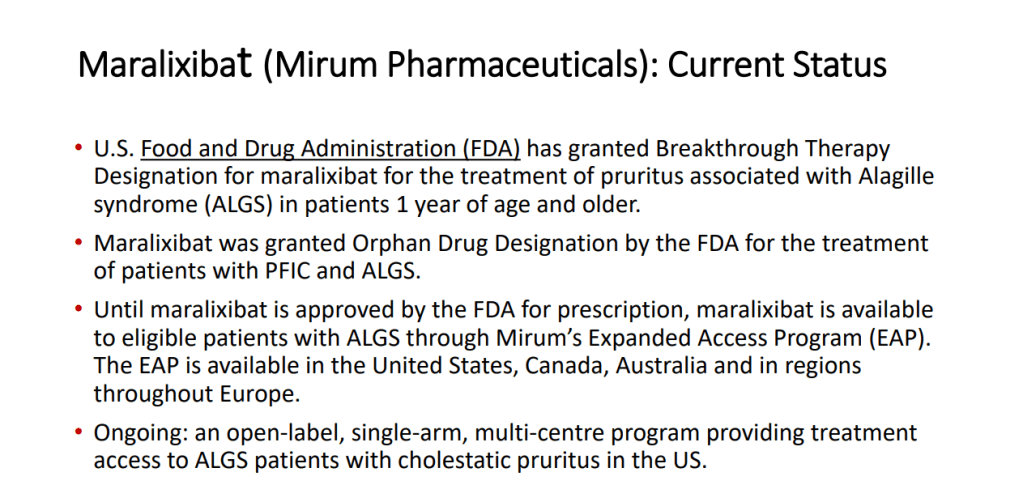

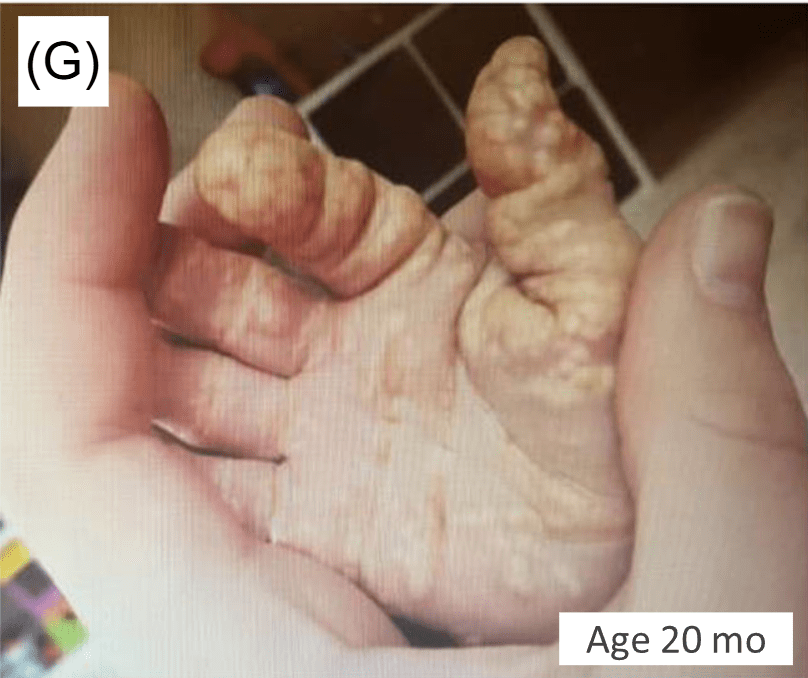

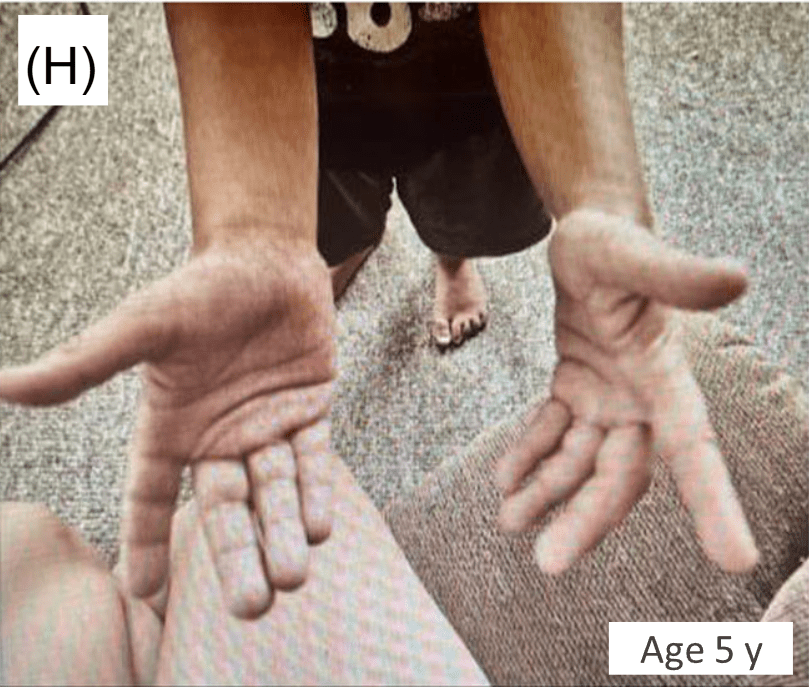

- Maralixibat (MRX) resulted almost complete resolution of severe, debilitating xanthomas and clinically meaningful improvements in pruritus/serum bile acid levels.

- Clinical scratch score in Case 1 dropped from baseline of 4 to 2 after MRX; in Case 2, it dropped from 3 to 1 after MRX

- Serum bile acids in Case 1 dropped from baseline of 468 micromol/L to 206 after MRX; in Case 2 it dropped from 57 to 25 after MRX

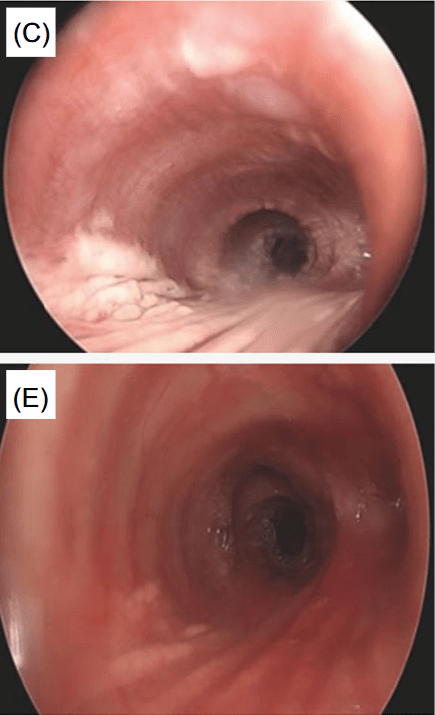

- This case report involved two patients with ALGS and unusual manifestations of xanthomatosis, including one patient with airway xanthomas and a second patient with severe, diffuse xanthomas

From Figure 1 showing airway and skin changes in case 1:

Discussion:

- “The ICONIC study by Gonzales et al. showed significant improvements in xanthomas in participants treated with maralixibat by 48 weeks, based on overall reductions in the Clinician Xanthomas Score, with further improvements in patients treated for longer durations. Xanthoma reduction was associated with improved quality of life and levels of TC.4 This report reviewed real-world experience in two patients with ALGS and characterized the extent of their improvement after treatment with maralixibat.”

My take: This report provides convincing evidence that maralixibat was associated with reversing severe xanthomas in these two patients with Alagille syndrome.

Related blog posts:

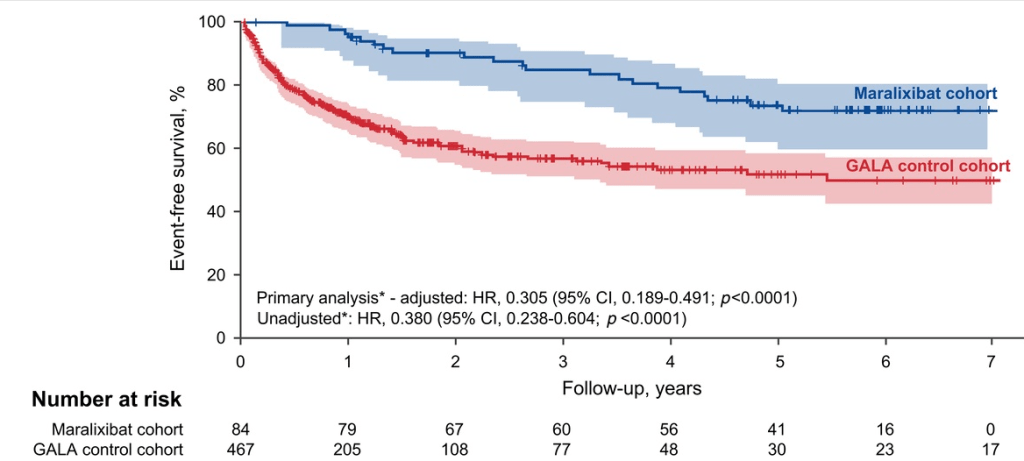

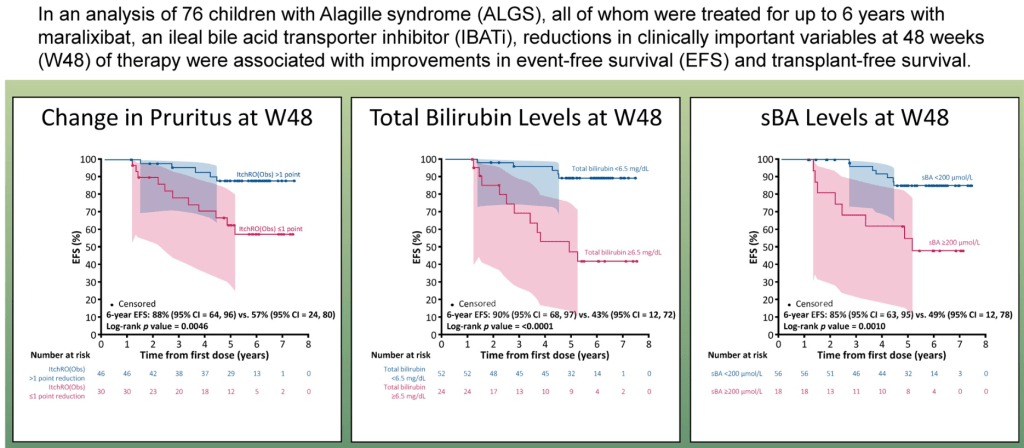

- Relooking at 6-Year Data of Maralixibat for Alagille Syndrome

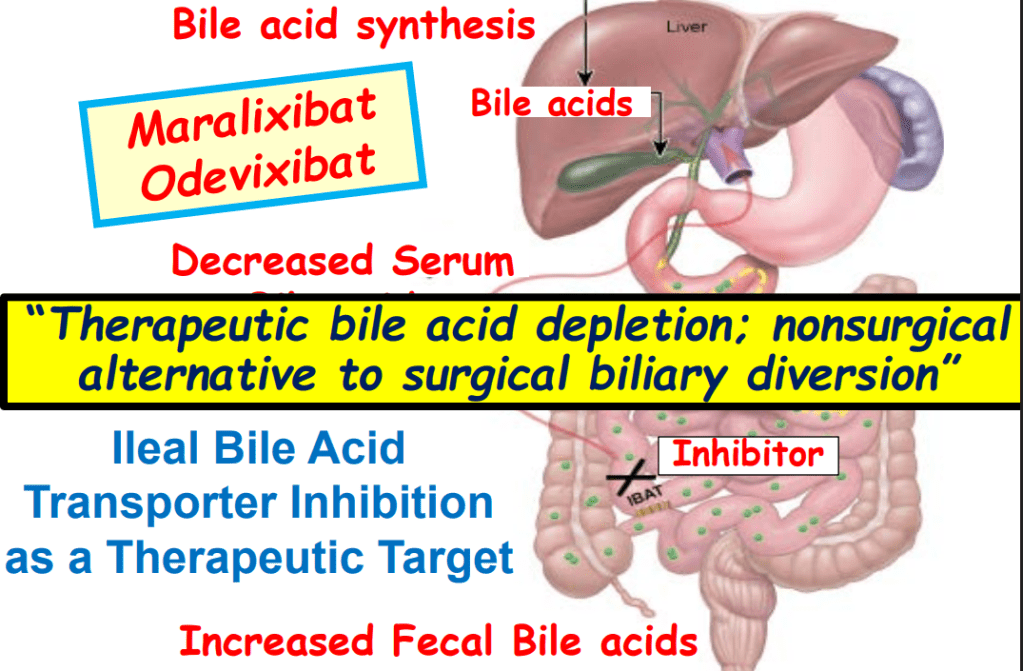

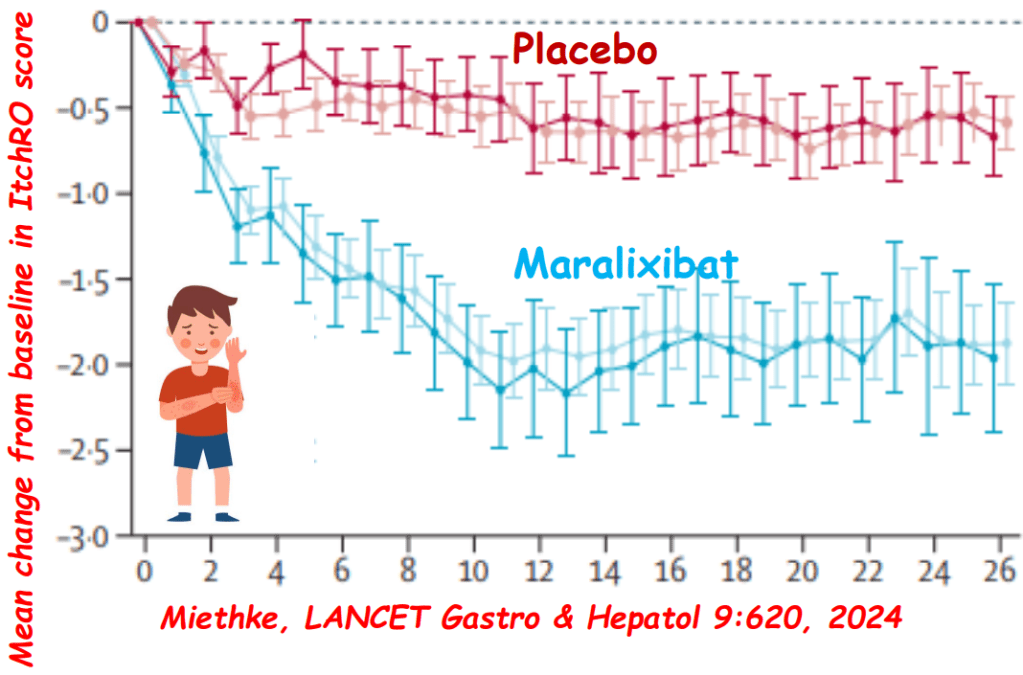

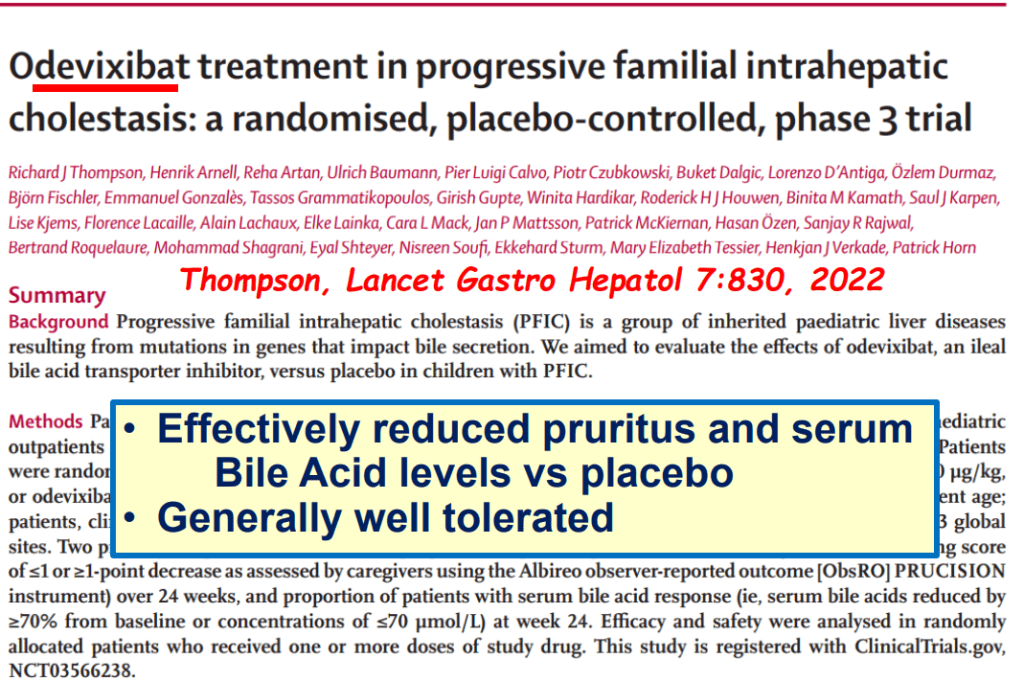

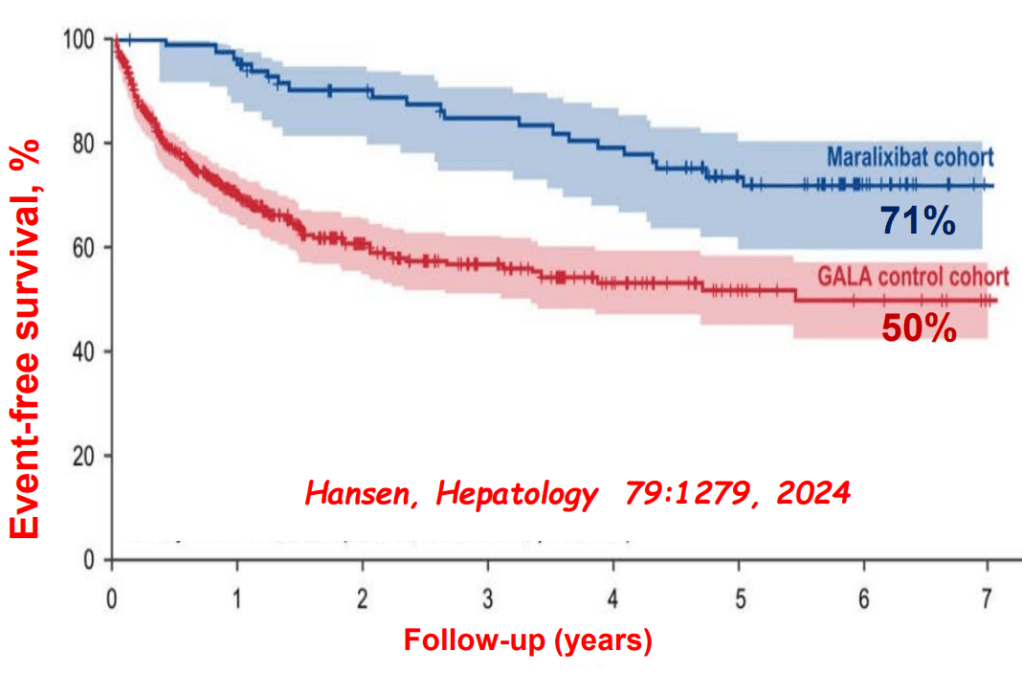

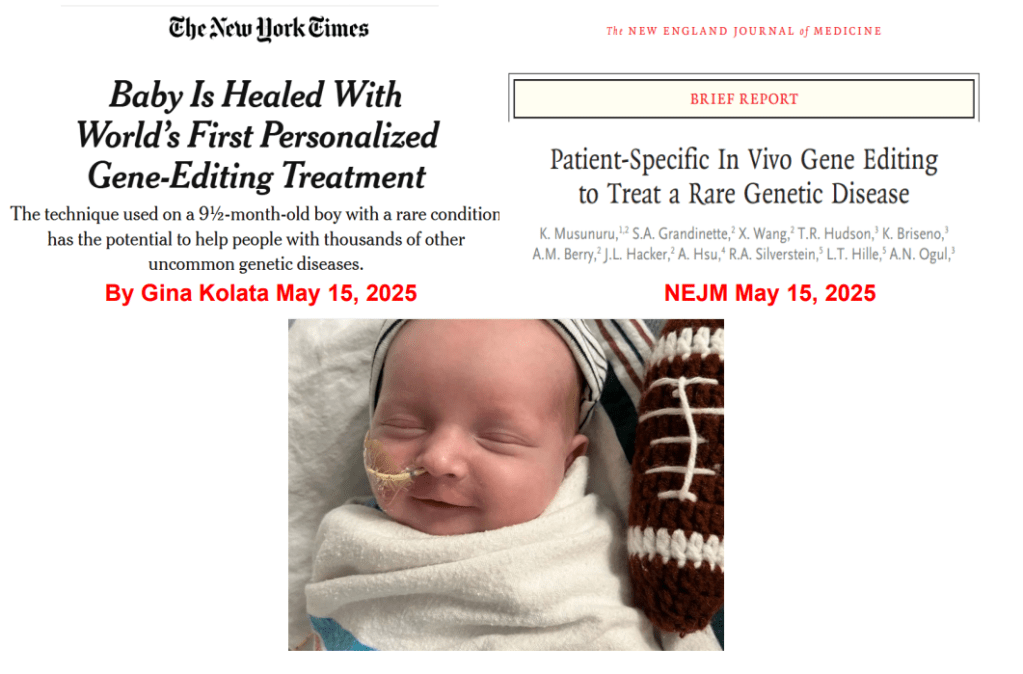

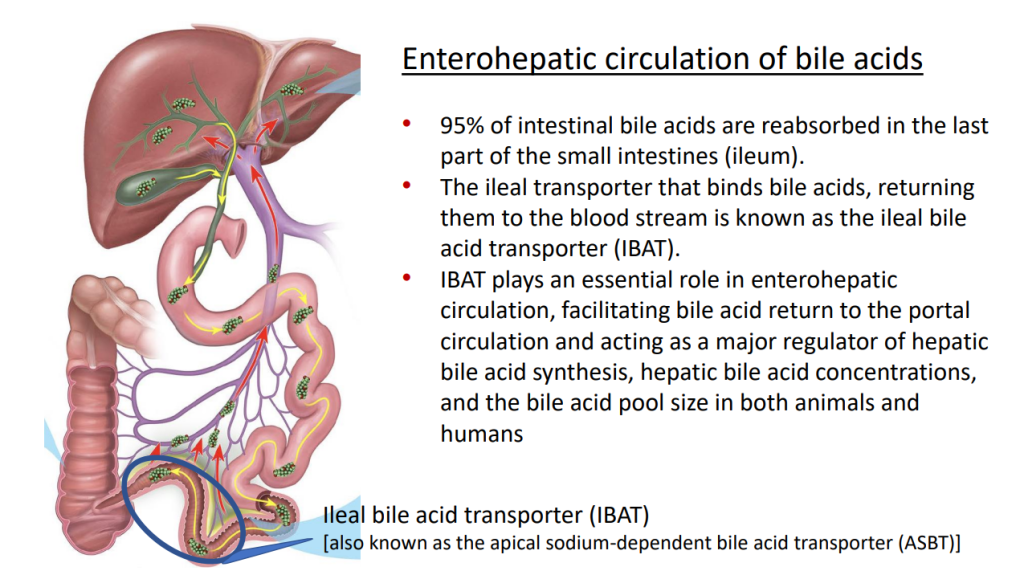

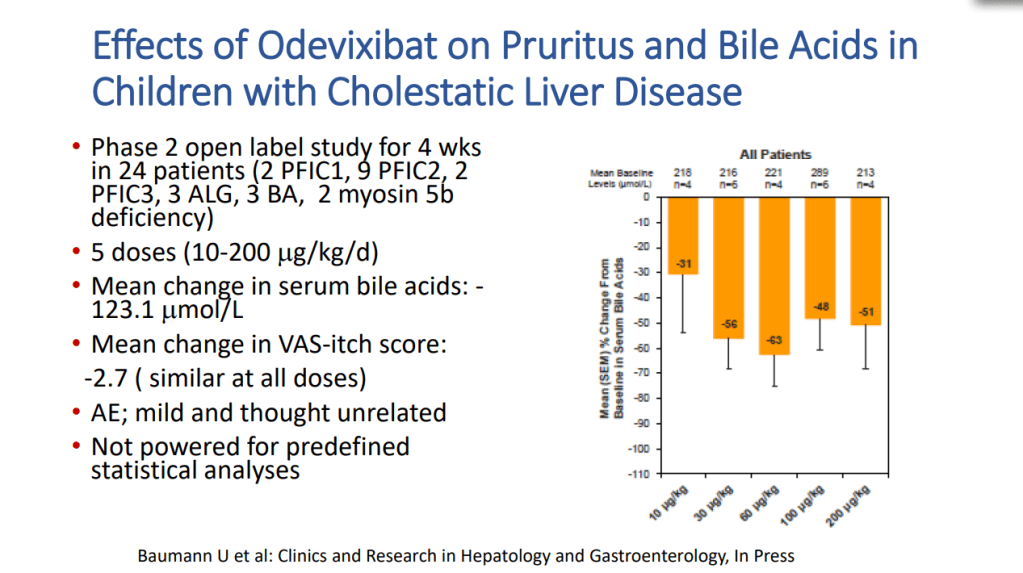

- New Era in Cholestatic Liver Diseases

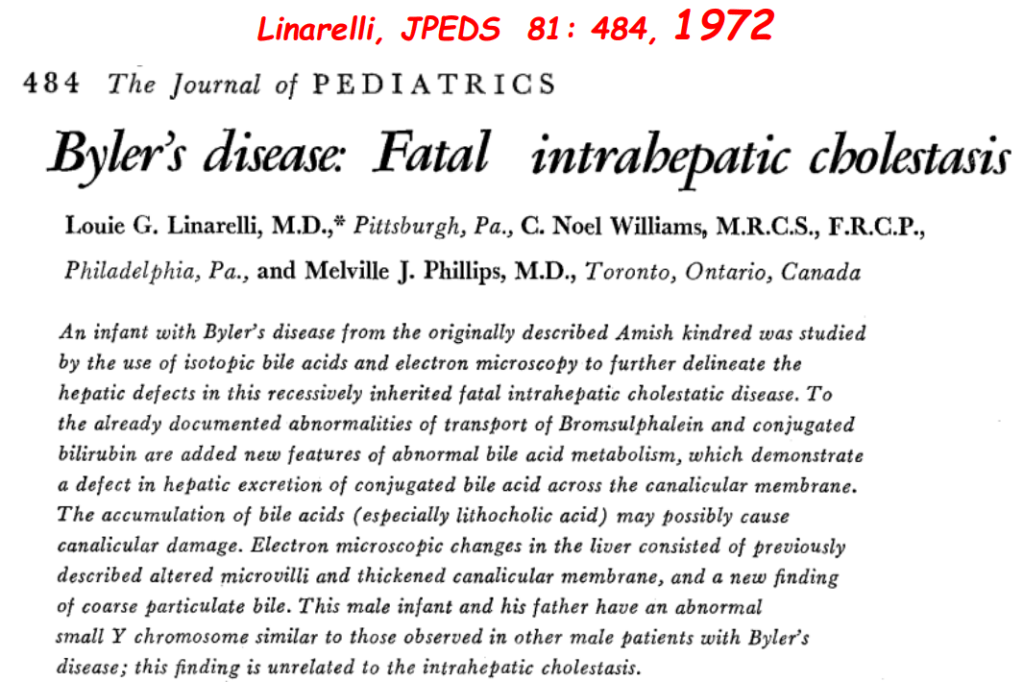

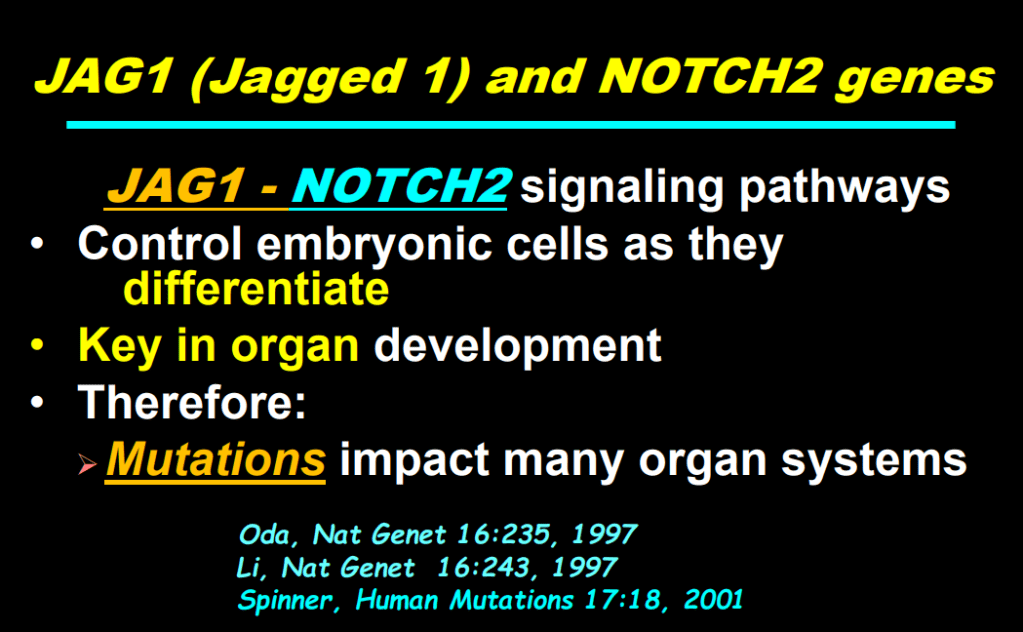

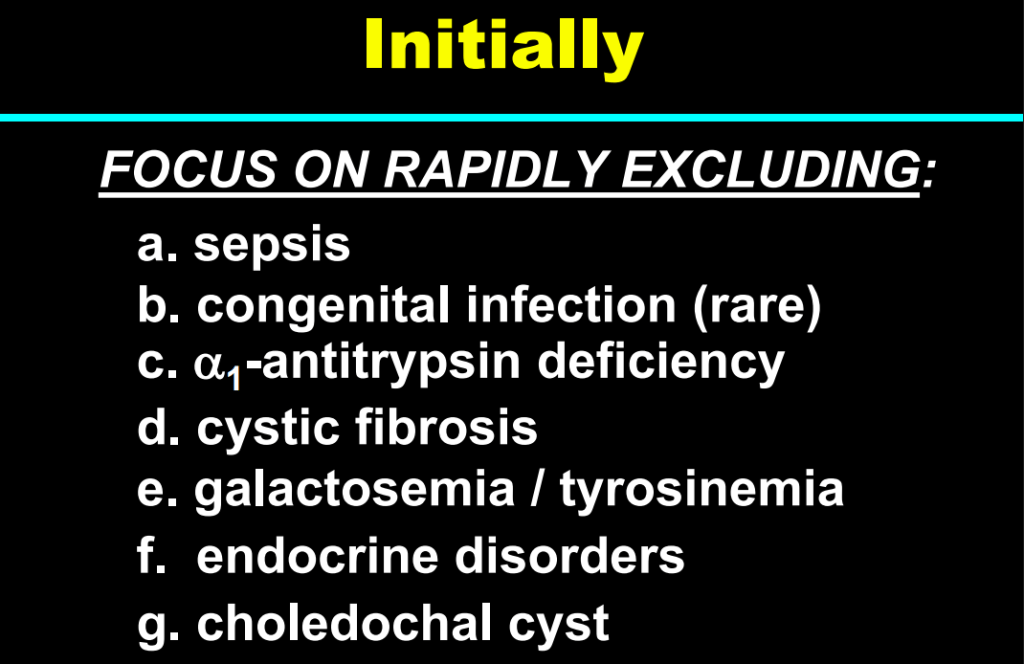

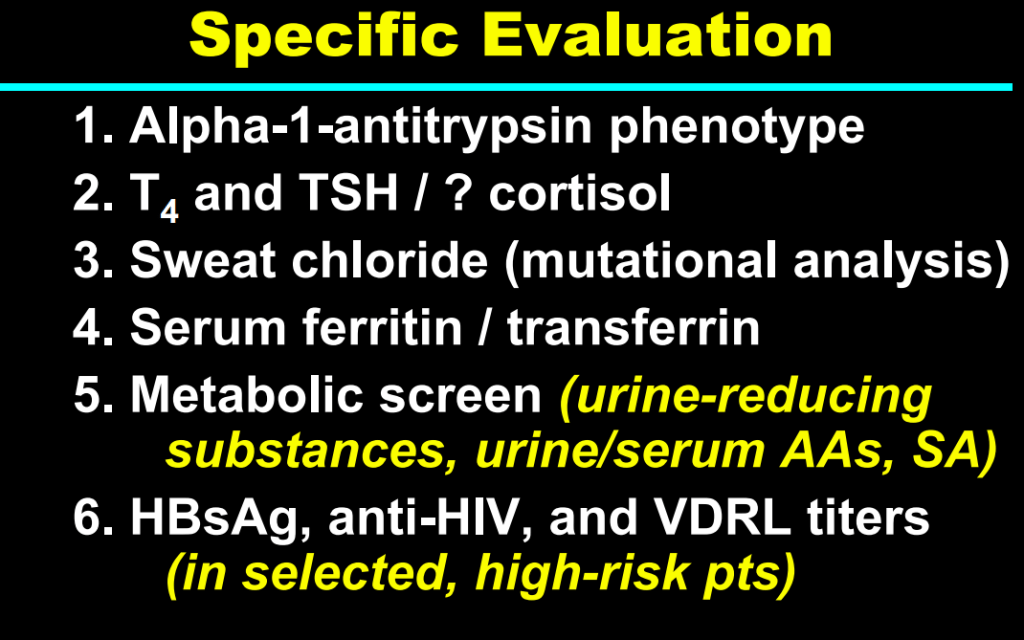

- Dr. William Balistreri: Whatever Happened to Neonatal Hepatitis (Part 2)

- Dr. William Balistreri: Whatever Happened to Neonatal Hepatitis (Part 1)

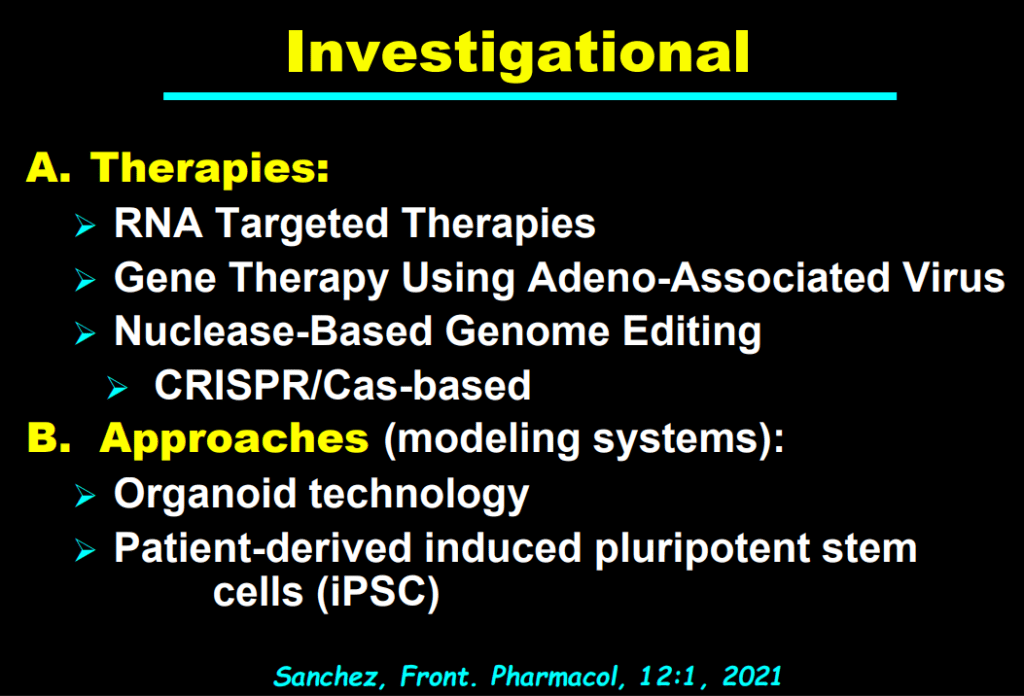

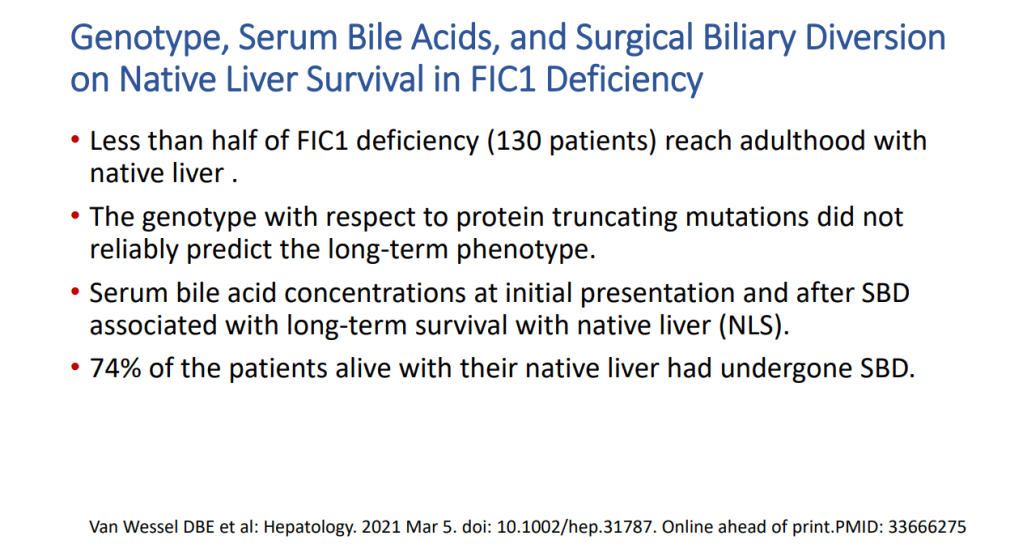

- Advancements in Pediatric Cholestatic Liver Disease Management

- Six Year Data for IBAT Inhibitor Treatment for Alagille Syndrome

- Lecture: IBAT Inhibitor for Alagille Syndrome

- GALA: Alagille Study

- Liver Briefs: HLH in Infancy, Maralixibat for Alagille Syndrome, Liver Disease Due to Inborn Errors of Immunity

- NASPGHAN Alagille Syndrome Webinar

- Intracranial Hypertension & Papilledema with Alagille Syndrome

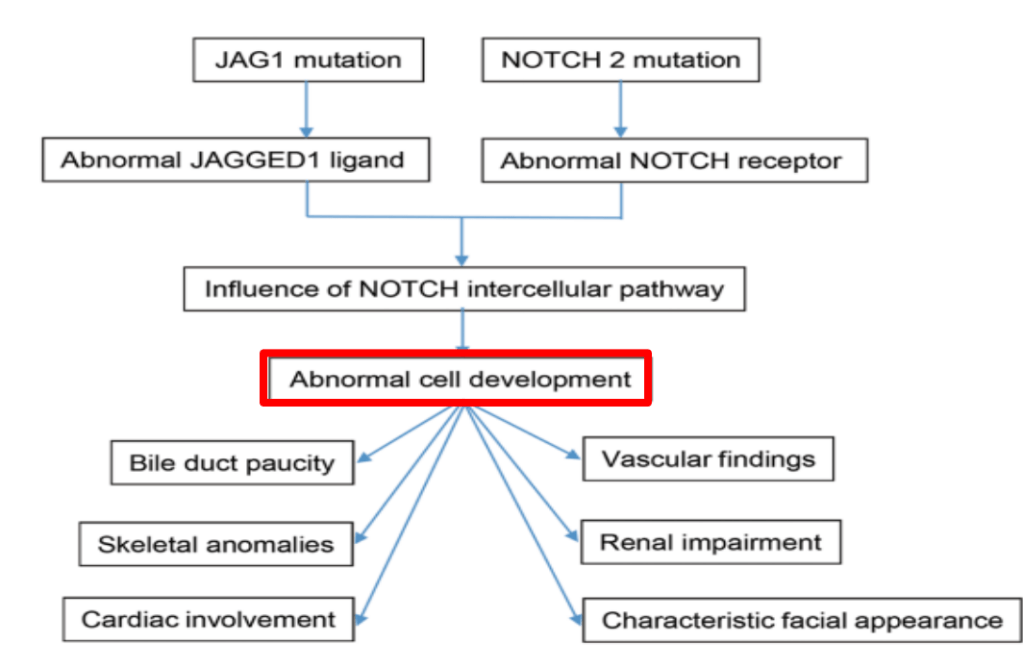

- Explaining Differences in Disease Severity for Alagille Syndrome

Disclaimer: This blog, gutsandgrowth, assumes no responsibility for any use or operation of any method, product, instruction, concept or idea contained in the material herein or for any injury or damage to persons or property (whether products liability, negligence or otherwise) resulting from such use or operation. These blog posts are for educational purposes only. Specific dosing of medications (along with potential adverse effects) should be confirmed by prescribing physician. Because of rapid advances in the medical sciences, the gutsandgrowth blog cautions that independent verification should be made of diagnosis and drug dosages. The reader is solely responsible for the conduct of any suggested test or procedure. This content is not a substitute for medical advice, diagnosis or treatment provided by a qualified healthcare provider. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a condition.