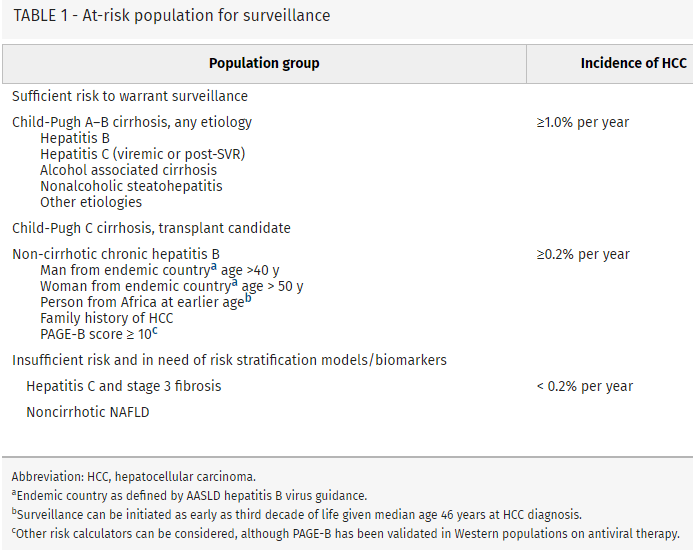

AG Singal et al. Hepatology 2023; 78: 1922-1965. Open Access! AASLD Practice Guidance on prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma

This article has 50 recommendations for prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. I will focus on prevention/screening in this post as this is most relevant to pediatric practice.

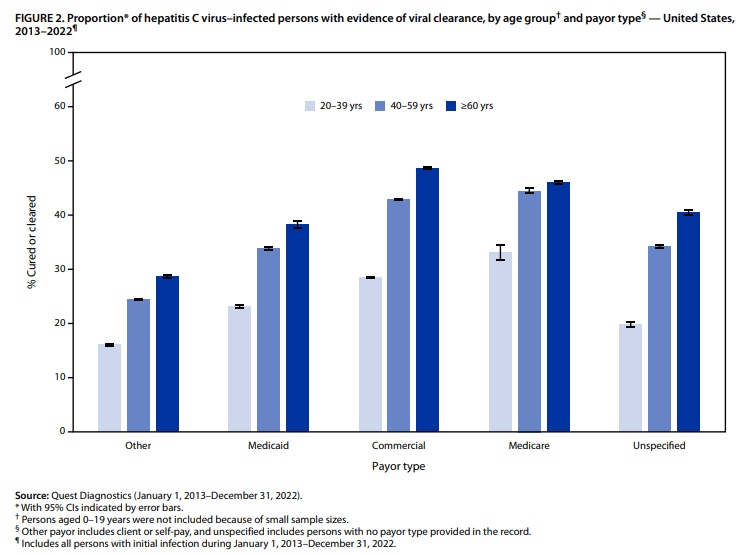

Figure 3 provides data supporting benefits of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) surveillance. HCC surveillance has been shown to significantly reduce HCC-related mortality in a randomized controlled trial among patients with chronic HBV infection and in several cohort studies among patients with cirrhosis from any etiology.

Who to screen for HCC:

Key Recommendations on Surveillance:

My take: This guidance recommends ultrasound and AFP monitoring every 6 months in those at high risk of developing HCC. Most pediatric patients would not require surveillance based on this guidance.

Related blog posts:

- Quantifying the Cancer Risk (Mainly HCC) in Adults with NAFLD

- Should All Pediatric Patients with Hepatitis B Undergo Routine Surveillance for Hepatocellular Carcinoma?

- Fatty Liver Disease AASLD Practice Guidance 2023

- Current Practice in Hepatitis B and Long-term Prospects

- Hep B-related Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Kids: 8 Needles in 4 Haystacks

- Does Screening for Hepatocellular Carcinoma Improve Outcomes in Patients with Cirrhosis?

- HBV Vaccination Prevents Cancer In Taiwan: HCC incidence per 105 person-years was 0.92 in the unvaccinated cohort and 0.23 in the vaccinated birth cohorts.

- Increasing Incidence of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in the U.S.

- Causes of Death with Hepatitis B in U.S.

- Do antivirals lower the risk of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in HBV?