F Ahmed, M Abu-El-Haija. Gastroenterol 2025; 169: 572-584. Open Access! Acute Pancreatitis in Children: It’s Not Just a Simple Attack

This is a really good review of acute pancreatitis covering epidemiology, diagnosis, severity classification, management, microbiome/metabolite derangements, genetics, and complications. Most of these topics have been covered in numerous blog posts (see below).

Selected Key Points:

- Diagnostic testing -Amylase/Lipase: “The diagnostic efficacy of amylase for AP, in terms of sensitivity and specificity, is contingent on the selected threshold value. Elevating the cut-off point to 1000 IU/L results in a high specificity of approximately 95%. However, this comes at the cost of reduced sensitivity, which some studies report to be as low as 61%… the activity of serum lipase remains elevated for a longer duration, typically between 8 and 14 days,… Lipase demonstrates superior accuracy with most studies reporting specificities exceeding 95% and sensitivities ranging from 55%–100% at a threshold activity level of 600 IU/L…hese tests have excellent sensitivities, they may have a few limitations such as being poor predictors of severity”

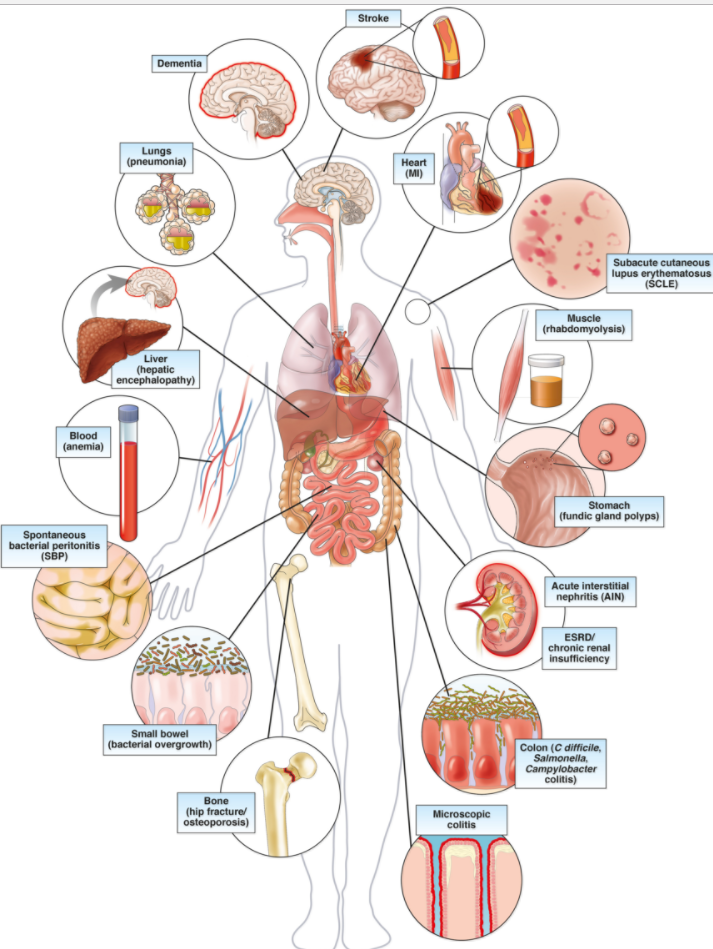

- Risk Factors in Children (from Figure 1):

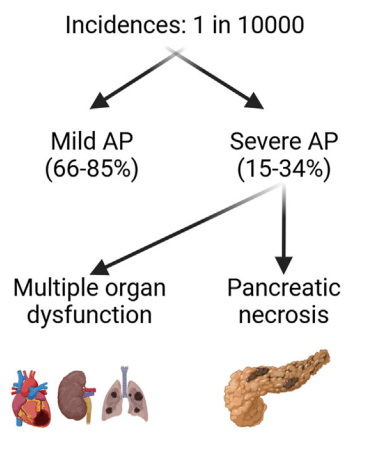

- Incidence and Severity in Children (from Figure 1):

[At a recent lecture, Jay Freeman (How to Upgrade Pancreas Care –Jay Freeman MD (Part 1)) noted that severe pancreatitis is often defined by degree of organ dysfunction (eg. cardiac, pulmonary, renal). A practical definition of severe pancreatitis in children is whether the patient requires admission to an ICU]

- Diagnostic testing -Imaging: “Imaging techniques are crucial for diagnosing and managing AP in children…NASPGHAN) and the Society for Pediatric Radiology formed consensus guidelines where transabdominal ultrasonography was recommended as the primary imaging technique for pediatric cases with suspected AP…Recent studies in the pediatric population have indicated that US’s sensitivity for AP detection ranges from 47%–52%.25 …Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) is useful for anatomical assessment without radiation but may require sedation”

- Management: “The cornerstones of therapy are early feeding and intravenous fluids… Allowing patients to eat on admission was feasible and was associated with lower length of stay. Rates of intravenous fluids are recommended at 1.5–2 times maintenance rates,49 and the preferred fluid is Lactated Ringer’s due to limited studies including a recent randomized controlled study that showed that Lactated Ringer’s was associated with a faster discharge rate when administered compared with normal saline.50“

- Genetics: “A recently conducted study investigated the importance of genetics in pediatric AP patients…use of an extensive panel of 8 genes… PRSS1, CFTR, SPINK1, CPA1, CTRC, CLDN2, CASR, and SBDS… genetics is a major component in all types of pancreatitis in children, with genetic variants being most prevalent in CP cases at 31%, followed by AP at 19%, and ARP at 6%. A key discovery was that variants in SPINK1, CFTR, or PRSS1 genes were associated with faster progression from first episode of AP toward CP.53“

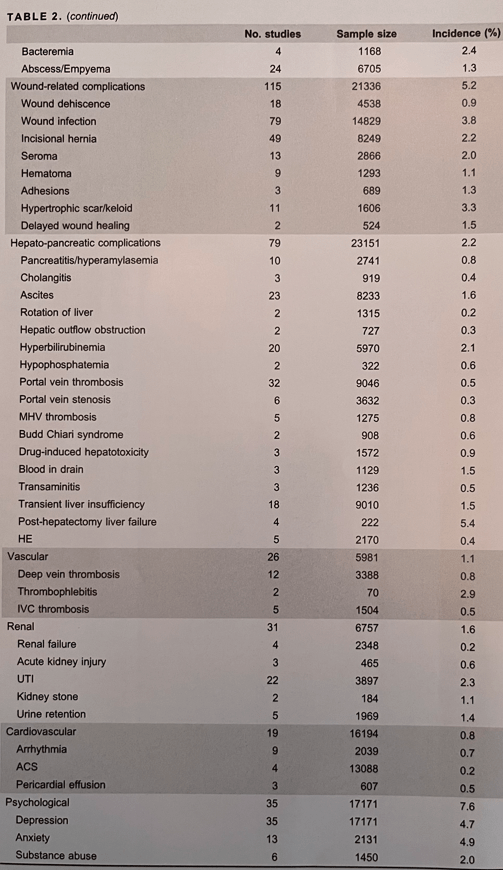

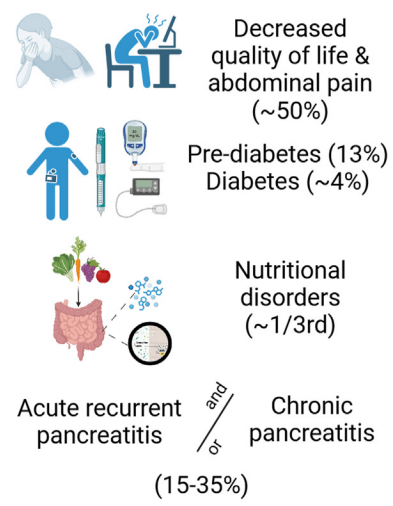

- Complications (from Figure 1): “After the first episode of AP, the QoL is decreased, and it may lead to other disorders such as exocrine dysfunction, endocrine dysfunction and diabetes, nutritional deficiencies, and acute recurrent pancreatitis and CP.”

My take: Even after a single episode of acute pancreatitis, there are risks for long-term complications and patients need to follow-up.

Related blog posts:

- How to Upgrade Pancreas Care –Jay Freeman MD (Part 1)

- How to Upgrade Pancreas Care –Jay Freeman MD (Part 2)

- How Triglycerides Affect Outcomes in Pediatric Pancreatitis

- Optimizing Fluid Resuscitation in Pediatric Acute Pancreatitis

- Here’s the Data: Endocrine Insufficiency After Acute Pancreatitis in Children

- Common Mistakes When Managing Acute Pancreatitis

- Medical Management of Chronic Pancreatitis in Children

- Acute Pancreatitis in Children with Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- NASPGAN Paper: Surgery for Chronic Pancreatitis: Choose Your Operation and Surgeon Carefully

- More Data Supporting Lactated Ringers for Acute Pancreatitis

- Imaging Recommendations for Pediatric Pancreatitis

- Diabetes Mellitus Associated with Acute Recurrent and Chronic Pancreatitis

- How Good Are Our Tests for Acute Pancreatitis?

- Choledochal Cyst and Pancreatitis

- Pediatric Pancreatitis -Working Group Nutritional Recommendations

- Consensus Pancreatitis Recommendations

- Acute Pancreatitis: NASPGHAN Clinical Report.