Editor’s note: This is the 5000th post on this blog! The first post was on December 7th, 2011.

CP Gyawali et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2025; 23: 2459-2467. Open Access! pH Impedance Monitoring on Proton Pump Inhibitor Therapy Impacts Management Decisions in Proven GERD but Not in Unproven GERD

Methods: Prospective 2-center study enrolled adult patients (n=79) with typical reflux symptoms with incomplete PPI response; they were studied both off PPI (wireless pH monitoring) and on PPI (pH-impedance monitoring)

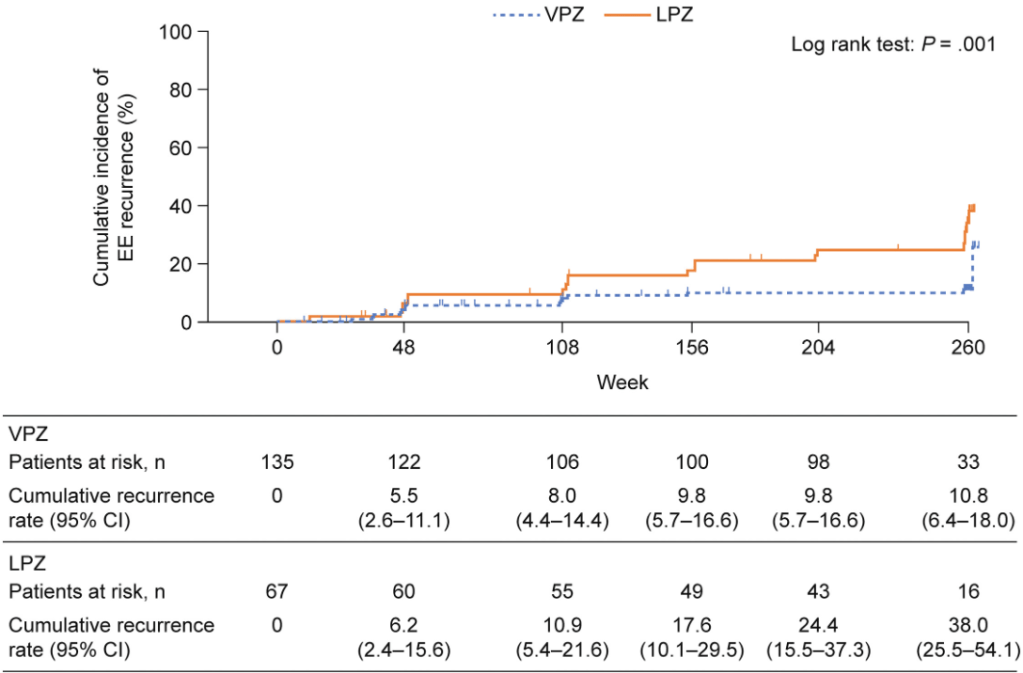

Key findings:

- In 60 patients with proven GERD off-PPI, 56.7% had no ongoing GERD on PPI (despite reflux symptoms)

- In unproven GERD, pH-impedance monitoring on acid suppressive therapy is unable to differentiate non-GERD symptoms from controlled GERD in the majority of patients, or identify patients who could benefit from discontinuation of acid suppression

Discussion points:

- “Only a small proportion of PPI nonresponders have true GERD, and most have either no GERD or overlap between inconclusive GERD and a non-GERD process such as an esophageal disorder of gut-brain interaction (E-DGBI).10,11“

- “On-therapy pH-impedance monitoring can identify refractory GERD in patients with previously proven GERD.”

- “Definitive GERD evidence and persisting symptoms despite optimized PPI therapy is an indication for escalation of management.20… potassium competitive acid blockers provide better healing of advanced grade esophagitis21 as well as faster symptom response in nonerosive reflux disease,22,23 and could be an option”

My take:

- Simple rule: Only perform on-therapy pH-impedance monitoring in patients with proven GERD

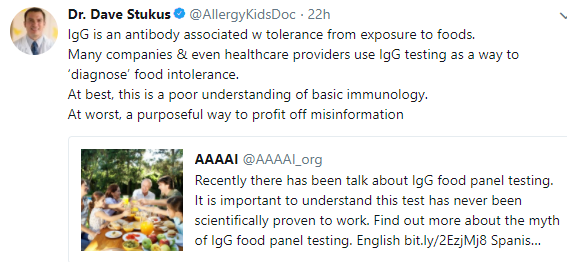

- Many patients with GERD symptoms do not have GERD (see posts below)

- In patients with documented GERD, on therapy pH monitoring can be helpful in proving refractory GERD which may benefit from alternative treatments

Related blog posts:

- How helpful is a pH-Impedance Study in Identifying Reflux-Induced Symptoms?

- What’s Going On in Patients with Reflux Who Fail to Respond to PPIs?

- How Many Kids with Reflux Actually Have Reflux?

- How to Make a Study Look Favorable to Surgery for Reflux over Medical Therapy

- Why didn’t patient with documented reflux get better with PPI …

- Failure of PPI test | gutsandgrowth

- Guidelines on Functional Heartburn

- Better to do a coin toss than an ENT exam to determine reflux

- How Likely is Reflux in Infants with “Reflux-like … – gutsandgrowth