Overall, 12-19% of Americans are affected by chronic constipation (Am J Gastroenterol 2004; 9: 750-59). Despite the fact that constipation problems are widespread, the amount of useful research available to guide treatment is quite limited. Two recent articles do offer some information:

- Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011; 9: 577-83.

- Gut 2011; 60: 209-18.

The first reference examined the use of bisacodyl in a randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled study in the UK. During the 4-week treatment period, patients receiving 10mg/day bisacodyl (n=247) had increased stools, from 1.1 per week to 5.2 per week. Stool frequency also increased to 1.9 per week in the placebo group (n=121). All secondary endpoints including constipation-associated symptoms (eg. quality of life indices, physical discomfort) improved significantly compared to placebo. Average age of patients in this study was 55 years. The main adverse effect was diarrhea –mainly during the 1st week of therapy.

A selected summary in Gastroenterology (Gastroenterology 2012; 142: 402-404) reviews the first study and makes several useful points:

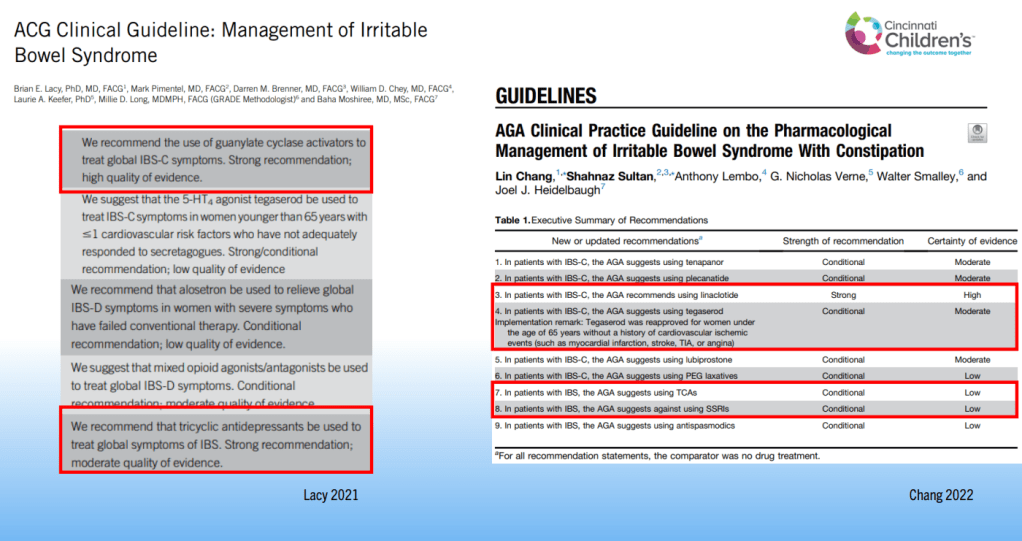

- Stimulant laxative use has been hindered by myths & misconceptions along with lack of supporting data. Most recent studies do not support a role of stimulant use in causing enteric neuropathies, a cathartic colon or increasing the risk of colon cancer

- Osmotic laxatives have been favored in guidelines but this has not been bolstered by supporting data

- Only recently have two large randomized controlled studies proven the efficacy and safety of stimulant laxatives over the short-term

- Long-term prospective studies are not available on the use of stimulant laxatives.

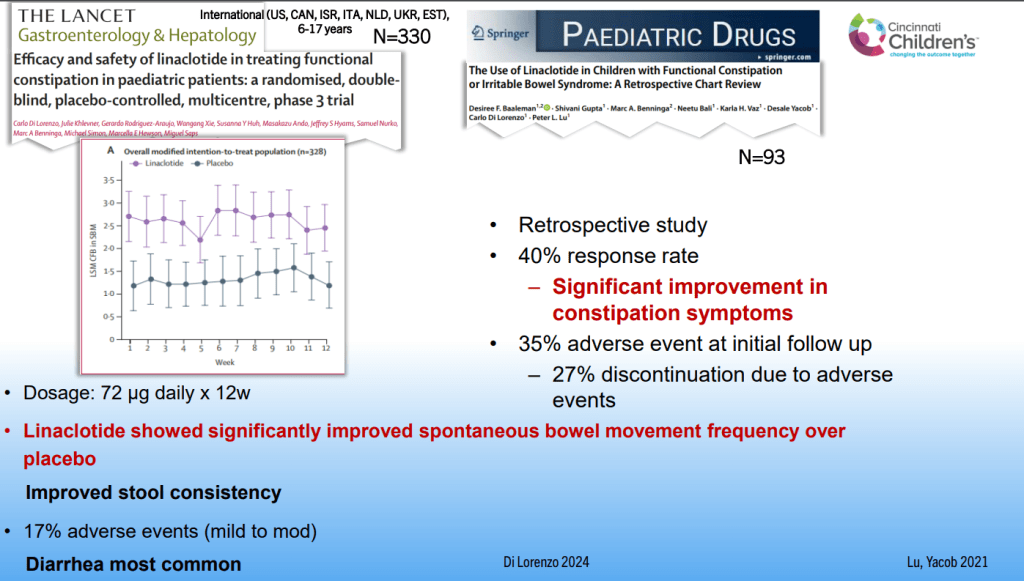

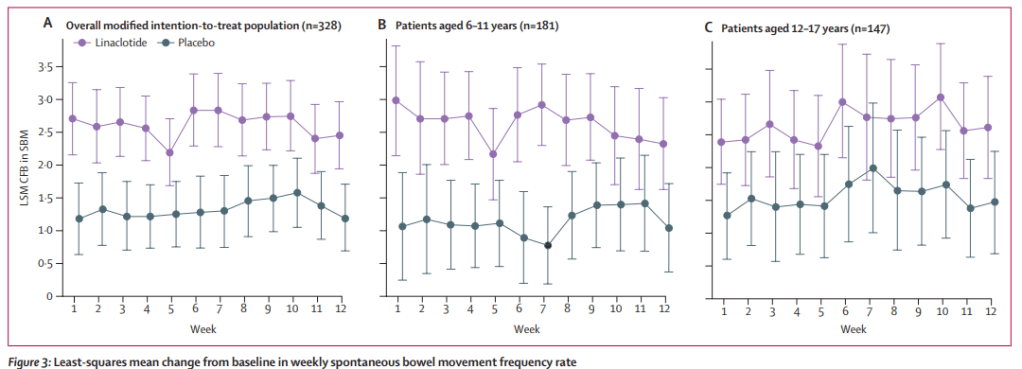

The second reference is a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of pharmacologic therapy for chronic idiopathic constipation. Twenty one eligible RCTs were identified: eight laxative studies (n=1411), seven prucalopride studies (n=2639), three lubiprostone (n=610), and three linactolide trials (n=1582). All of these studies showed treatment was superior to placebo. These studies involved subjects who were mainly adults (>90% older than 16 years).

The results showed benefit from both stimulant and osmotic laxatives. Overall, the osmotic and stimulant laxative studies showed higher response than the pharmacologic agents like prucalopride, lubiprostone, and linaclotide. Nevertheless, between 50% and 85% of patients did not fulfill criteria for response to therapy.

Additional references:

- -J Clin Gastro 2003; 36: 386-389. Safety of stimulants for long-term use.

- -Am J Gastro 2005; 100: 232-242. Myths about constipation. Stimulants have not been proven to cause a “cathartic colon”

- -J Pediatr 2009; 154: 258. Constipation associated w 3-fold increase in health utilization/cost.

- -Clin Gastro Hep 2009; 7: 20. Review of complications assoc c constipation in adults.

- -Pediatrics 2008; 121: e1334. Behavioral therapy ineffective in treating childhood constipation.

- -NEJM 2008; 358: 2332, 2344. Use of methylnatrexone for opioid-induced constipation & trial of n=620 of prucalopride for severe constipation. Both drugs were helpful.

- -Gastroenterology 2004; 126: S33. Review of pediatric incontinence.

- -J Pediatr 2004; 145: 253-4. Prevalence of encopresis 15% /constipation 23% in obese children (n=80). Questionnaire administered to 80 consecutive obese children.

- -Gastroenterology 2003; 125: 357. Longterm constipation followup. one-third with persistent constipation; 60% better at 1 year. (tertiary referral group)

- -Pediatrics 2004; 113: 1753 & e520. When constipation & toileting difficulties both occur, constipation usually precedes toileting problems