- A Blasi et al. Liver Transplantation 2025; 31: 269-276. A multicenter study of the risk of major bleeding in patients with and without cirrhosis undergoing percutaneous liver procedures

- Editorial: A Rabiee et al. Liver Transplantation 2025; 31: 259-261. Open Access: Risk of bleeding after percutaneous liver procedures in patients with cirrhosis: Myth or fact?

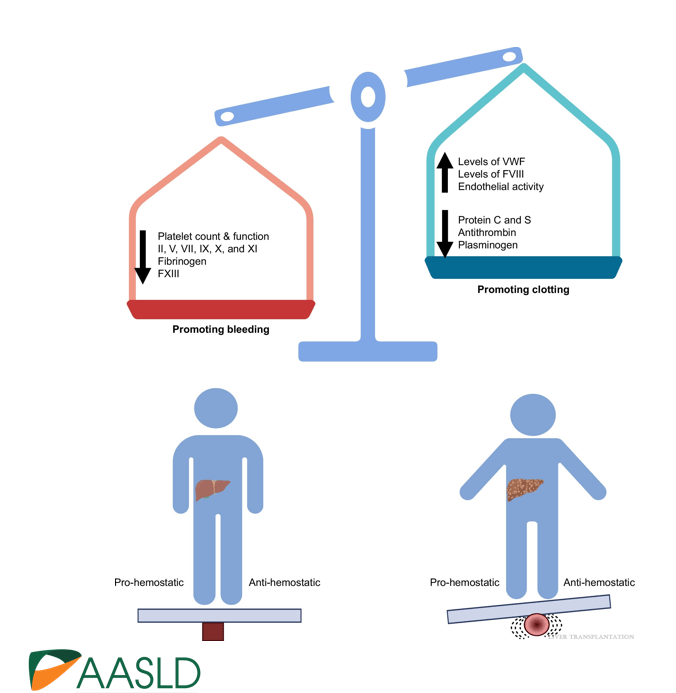

Background: “The most important factor contributing to bleeding risk in patients with liver disease is related to the presence of portal hypertension rather than coagulation abnormalities.1 The changes in the coagulation system in patients with cirrhosis create a re-balanced state, which is prothrombotic. Despite this well-known pathophysiology and recommendation against routine transfusion of blood products (especially fresh frozen plasma) by major guidelines, platelet and fresh frozen plasma transfusion remain a common practice before percutaneous liver procedures.2,3“

Methods: In this retrospective study from three centers in Spain, the researchers enrolled 1797 adults including 316 with cirrhosis (97% had compensated disease). They established a protocol that allowed, at the discretion of the radiologist, to transfuse patients with FFP or platelets if INR was 1.5 or greater or if platelets were 50,000 or below. The primary outcome of the study was major bleeding, which was defined as a drop in hemoglobin (2 or more units) or a need for transfusion of 2 or more units of blood within 1 week after the procedure. This study enrolled patients who underwent percutaneous liver biopsy (86% of cohort) and percutaneous ablation of liver tumors (14% of cohort). Only 6/25 (24%) with INR >1.5 received FFP. 16/22 (72%) with platelet counts below 50,000 received a platelet transfusion. Overall, 7 patients received FFP (1 with cirrhosis, 6 without) and 35 patients received platelets (16 with cirrhosis, 19 without).

Key findings:

- Only 14 patients (0.8%) experienced major bleeding after the procedure, and there was no difference between those who had a diagnosis of cirrhosis versus those without cirrhosis. Bleeding occurred in 0.6% of patients with cirrhosis compared to 0.8% of those without.

- Only 1 patient with an ablation procedure had major bleeding

- Patients with a diagnosis of cirrhosis were more likely to receive a transfusion of any kind

- Among those with major bleeding, none met the criteria for transfusion. That is, “no variable was identified to predict the risk of major bleeding.”

My take (borrowed from editorial): This study reinforces the recommendation that “correction of coagulation markers before procedures is unnecessary.”

create a re-balanced state, which is prothrombotic.

Related blog posts:

- Time to Adjust the Knowledge Doubling Curve in Hepatology This post summarizes the following reference: PG Northup et al. Hepatology 2021; 73: 366-413 (346 references) Full text: Vascular Liver Disorders, Portal Vein Thrombosis, and Procedural Bleeding in Patients With Liver Disease: 2020 Practice Guidance by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases PDF version: Vascular Liver Disorders, Portal Vein Thrombosis, and Procedural Bleeding in Patients With Liver Disease: 2020 Practice Guidance by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Specific recommendations from this practice guidance: –For Platelets in the setting of cirrhosis: “Given the low risk of bleeding of many common procedures, potential risks of platelet transfusion, lack of evidence that elevating the platelet count reduces bleeding risk, and ability to use effective interventions, including transfusion and hemostasis if bleeding occurs, it is reasonable to perform both low‐ and high‐risk procedures without prophylactically correcting the platelet count...An individualized approach to patients with severe thrombocytopenia before procedures is recommended because of the lack of definitive evidence for safety and efficacy of interventions intended to increase platelet counts in patients with cirrhosis.” The authors note in Table 4, that the AASLD does not have a specific threshold for platelets, whereas other societies have used values of >30 or >50. –For INR in setting of cirrhosis: “The INR should not be used to gauge procedural bleeding risk in patients with cirrhosis who are not taking vitamin K antagonists (VKAs)…Measures aimed at reducing the INR are not recommended before procedures in patients with cirrhosis who are not taking VKAs…FFP transfusion before procedures is associated with risks and no proven benefits.”

- Briefly Noted: Outpatient Liver Biopsy

- Liver Biopsy -Risks and Benefits