In a previous blog post in 2019, it was noted how the IRS proved that having health insurance saved lives (How The IRS Proved That Health Insurance Saves Lives); just receiving a letter recommending getting coverage reduce deaths by ~1 in 1600. Another study in 2014 (in Massachusetts) showed that for “every 830 additional people who got insurance under Massachusetts’ health reforms prevented roughly one death.” If this were extrapolated to broaden health care coverage to everyone in the U.S this could amount to preventing 20,000-45,000 deaths per year (A Leading Cause of Mortality in U.S…. and 45,000 Unnecessary Deaths Per Year).

A new study shows how important ACA expansion has been to improved liver outcomes:

TL Walker et al. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2026; 24: 312 – 327. The Affordable Care Act Improves Access, Survival, and Racial Disparities of Patients With Liver Disease: A Systematic Review

This review identified twenty-seven studies that met inclusion criteria across 4 clinical categories: hepatitis C virus (n = 4), liver transplantation (n = 10), hepatocellular carcinoma (n = 9), and cirrhosis or CLD (n = 5).

Key findings:

- Twenty-three out of 27 studies showed patients benefited from the ACA, which notably included improved liver-related mortality in Medicaid-expansion (ME) states.

- “Difference-in-difference analyses showed liver transplantation listing increased by 1.8% to 6.0% in ME vs NME states; early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) diagnosis increased by 5.4%, and cirrhosis-related mortality rose more slowly in ME states (0.5–1.0 per 100,000 vs 1.4–10.4 per 100,000).”

From Related summary: ACA expansion linked to better liver disease outcomes (GI & Hepatology News):

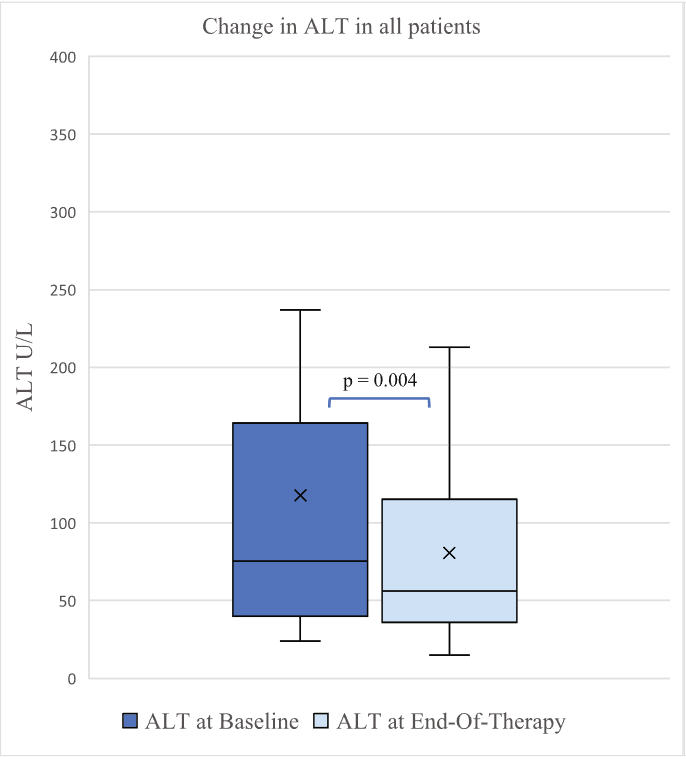

- HCV studies showed improved access to direct-acting antiviral therapy in ME states. Expansion states consistently reported higher direct-acting antiviral prescription rates and Medicaid reimbursement levels compared with NME states.

- HCC survival outcomes improved more consistently in ME than in NME states after ACA implementation (median overall survival, 7.3 months versus 4.5 months, respectively).

- Of the five studies that examined chronic liver disease and cirrhosis, ME was associated with lower emergency department readmissions, shorter hospital stays, and reduced hospitalization costs.

My take: The study findings, while not surprising, quantifies some of the improvements in survival and outcomes for patients who gained access to health insurance.

Related blog posts:

- Zip Code vs. Genetic Code

- Zip Code or Genetic Code -which is more important for longevity?

- 45,000 Unnecessary Deaths Per Year (2013): “45,000 American adults die each year because they have no medical coverage (Am J Public Health 2009; 99: 2289-95)”