Link from AAP HealthyChildren.org: Halloween Fun & Safety Tips for Kids of All Ages

S Zeneddin et al. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2025;81:960–966. Acid suppression after esophageal atresia repair: Some infants do benefit

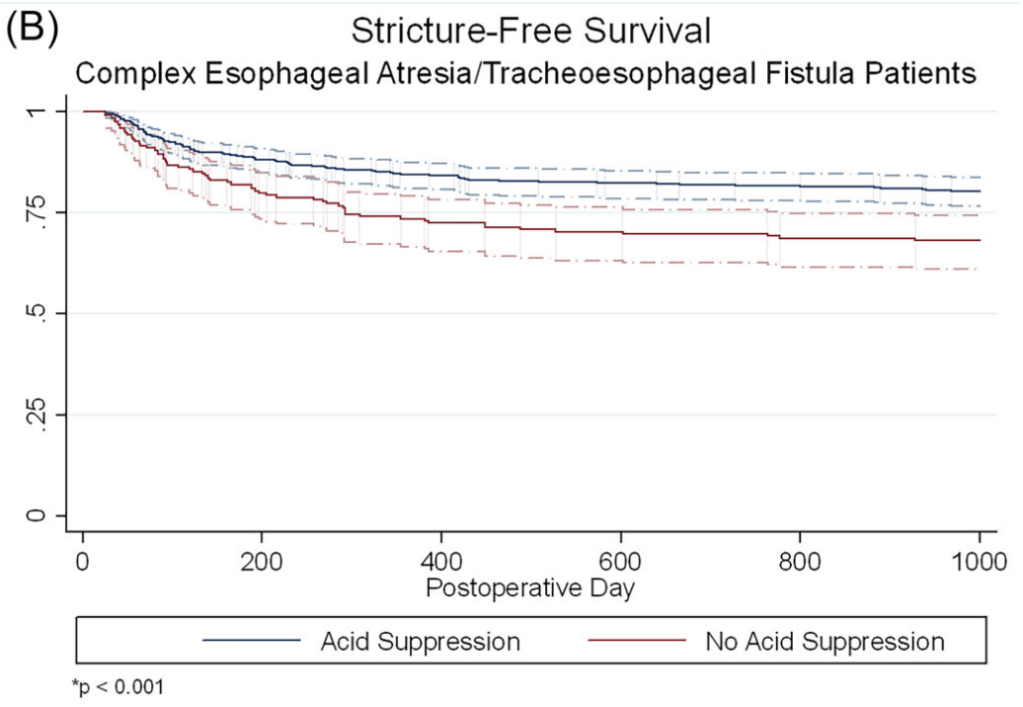

Methods: The authors performed a retrospective study using the Pediatric Health Information System for infants undergoing EA/TEF repair between 2010 and 2022 (n=1445 infants). Acid suppression was defined as receipt of an H2 blocker or proton pump inhibitor on the day of discharge or longer than 30 inpatient days. Complex EA/TEF repair was defined as delayed repair (>7 days), G-tube placement before repair (likely a sign of a long gap or type A anomaly), prolonged hospitalization (>60 days), or multiple inpatient fluoroscopies. The authors defined stricture solely if it required intervention.

Key findings:

- 257 (17.8%) required dilation by 1 year. Of the 688 (47.6%) infants who met criteria for complex EA/TEF, 126 (18.6%) required a dilation.

- At 1 year, stricture rate was similar in infants with simple EA/TEF, with or without acid suppression (17.5% vs. 17.0%, p = 0.90)

- In infants with complex EA/TEF, stricture rates were lower among those who received acid suppression compared to those who did not (15.3% vs. 26.0%, p = 0.001).

The associated editorial (D George, DK Robie. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2025;81:911–912) reviews some of the limitations of the study but does not provide clear recommendations on utilization of acid suppression therapy: the decision should be “should be individualized, weighing the potential benefits against the risks.”

My take: It is not surprising that more complex EA would have higher stricture rates. In my training (in the 1990s!), it was routine practice to use indefinite acid suppression. This article indicates that patients with low risk EA likely do not need acid suppression. In high risk patients, the algorithm by Yasuda et al (see post below J Am Coll Surg 2024; 238: 831-843) provides their approach to weaning acid suppression.

Related blog posts:

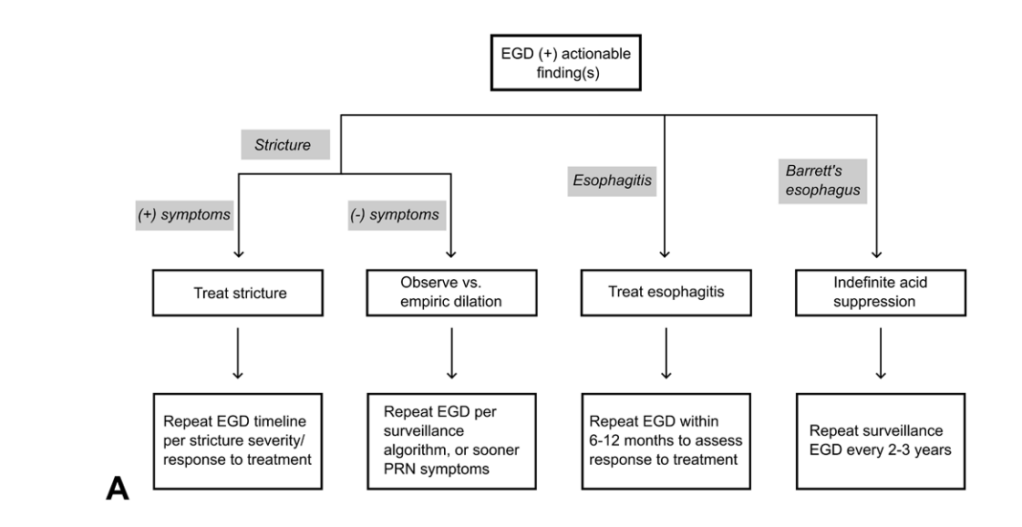

- Evidence-Based Algorithm for Surveillance in Esophageal Atresia Patients JL Yasuda et al. J Am Coll Surg 2024; 238: 831-843. The algorithms above suggest that at minimum, EA patients should have endoscopy every 5 years (likely starting between 12-18 months). More frequent endoscopy (every 2-3 years) may be worthwhile in those with risk factors (e.g. long gap EA, hiatal hernia, and prior esophagitis) and follow-up endoscopy is needed sooner if change in therapy (stricture dilation, esophagitis treatment or treatment de-escalation).

- Do PPIs Increase the Risk of Eosinophilic Esophagitis in Patients with Esophageal Atresia?

- How Effective are Stents for Anastomotic Esophageal Strictures in Patients with Esophageal Atresia

- More Often Than Not Esophagitis in Children with Esophageal Atresia is NOT due to Reflux

- How Bad is Reflux in Children with Esophageal Atresia?

- How Long Should Be PPIs Be Used in Patients with Esophageal Atresia?

- Endoscopic Surveillance after Esophageal Atresia: Low Yield in Pediatrics This study with 209 patients (Koivusalo et al. JPGN 2016; 62: 562-66) reported that “routine endoscopic surveillance had limited benefit and seems unnecessary” before 15 years of age.

Disclaimer: This blog, gutsandgrowth, assumes no responsibility for any use or operation of any method, product, instruction, concept or idea contained in the material herein or for any injury or damage to persons or property (whether products liability, negligence or otherwise) resulting from such use or operation. These blog posts are for educational purposes only. Specific dosing of medications (along with potential adverse effects) should be confirmed by prescribing physician. Because of rapid advances in the medical sciences, the gutsandgrowth blog cautions that independent verification should be made of diagnosis and drug dosages. The reader is solely responsible for the conduct of any suggested test or procedure. This content is not a substitute for medical advice, diagnosis or treatment provided by a qualified healthcare provider. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a condition.