G Trikudanathan et al. Gastroenterol 2024; 167: 673-688. Open Access (PDF)! Diagnosis and Management of Acute Pancreatitis

While this review focuses on acute pancreatitis in adults, there are areas of overlap with pediatric patients who have acute pancreatitis. Many of the points in this article were reviewed in the lecture by Dr. Freeman (summarized earlier this week).

A couple of details regarding these recommendations:

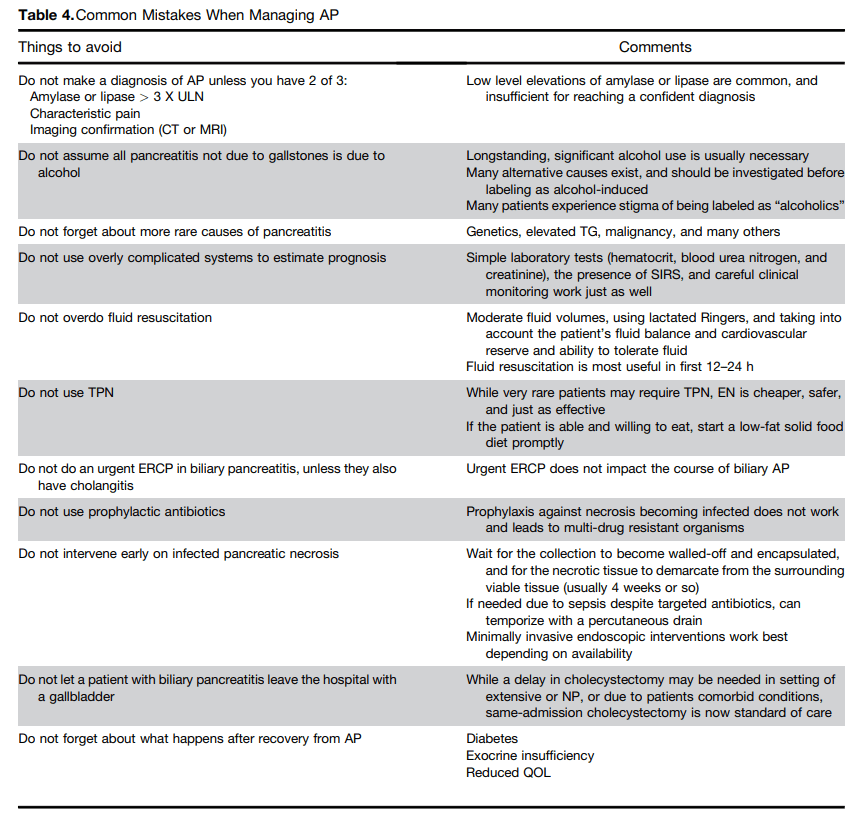

Nutrition: “Current guidelines recommend initiating early (as soon as tolerated)

oral feeding with solid (low-fat) diet in patients with predicted mild AP and this approach reduces length of hospitalization. Patients with severe AP or NP may be intolerant to oral diet…studies noted that the pancreas is largely insensitive to meal stimulation during AP. Early enteral nutrition (EN) was shown to have a beneficial trophic effect in preserving gut mucosal integrity and reducing gut bacterial translocation. EN was compared with TPN in AP in several RCTs and the results were statistically aggregated in several meta-analyses to

establish the superiority of EN in mortality, multiorgan failure, and rate of infection.”

TPN: “Given the cost burden, risk of catheter-related sepsis, electrolyte and metabolic derangement, and gut barrier failure, currently use of TPN is reserved for patients for whom EN is not possible or is not able to meet the minimum calorie requirements. It should be noted that although all guidelines advise avoiding TPN, it continues to be used.”

Antibiotics: “Current guidelines do not recommend prophylactic antibiotics in predicted severe AP or sterile necrosis because this practice is associated with the development of multidrug-resistant bacteria and fungal superinfection. It can be difficult in severe

pancreatitis to know if clinical deterioration is due to ongoing pancreatitis with SIRS, or due to a new infection. Procalcitonin is useful in distinguishing SIRS from bacterial sepsis. The PROCAP randomized trial used procalcitonin testing at 0, 4, and 7 days and weekly thereafter with a threshold of 1.0 ng/mL to guide initiation, continuation, and discontinuation of antibiotics. The procalcitonin based algorithm decreased the probability of being prescribed an antibiotic and the number of days on antibiotics without increasing infection or harm in patients with AP.”

Progression to Chronic Pancreatitis: “A systematic review and meta-analysis of progression showed that 10% of patients with first episode of AP and 36% of patients with recurrent AP develop CP, with risk being highest among smokers, alcoholic patients, and men.”

Risk of Diabetes: “A prior systematic review and meta-analysis of patients with an index attack of AP found that newly diagnosed diabetes occurred in 15% of individuals within 12 months, and risk increased 2-fold for diabetes after 5 years. The development of

diabetes was not significantly associated with the severity of pancreatitis, etiology of disease, patient age, or gender.”

Related blog posts:

- How to Upgrade Pancreas Care –Jay Freeman MD (Part 1)

- How to Upgrade Pancreas Care –Jay Freeman MD (Part 2)

- Medical Management of Chronic Pancreatitis in Children

- Acute Pancreatitis in Children with Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- NASPGAN Paper: Surgery for Chronic Pancreatitis: Choose Your Operation and Surgeon Carefully

- More Data Supporting Lactated Ringers for Acute Pancreatitis

- Imaging Recommendations for Pediatric Pancreatitis

- Diabetes Mellitus Associated with Acute Recurrent and Chronic Pancreatitis

- How Good Are Our Tests for Acute Pancreatitis?

- Choledochal Cyst and Pancreatitis

- Pediatric Pancreatitis -Working Group Nutritional Recommendations

- Consensus Pancreatitis Recommendations

- Acute Pancreatitis: NASPGHAN Clinical Report.