S Zielsdorf et al. Liver Transplantation 2025; 31: 832-835. PRO: All pediatric transplant centers should have LDLT as an option

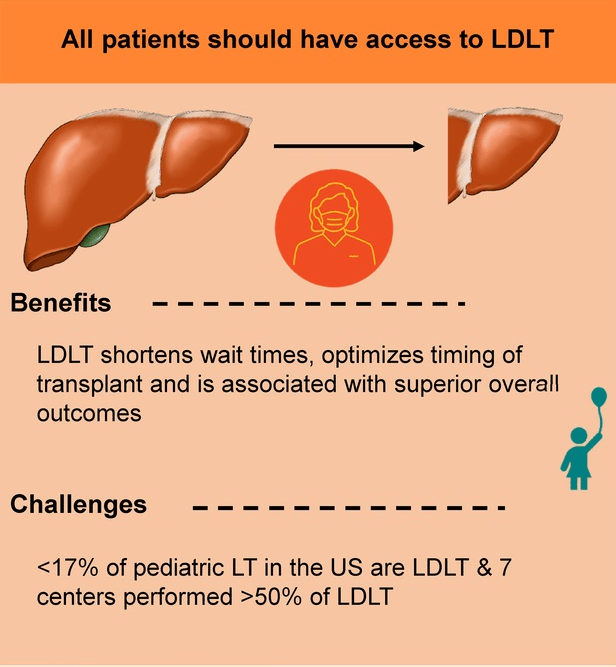

Zielsdorf et make a compelling argument that all liver transplant patients should have access to LDLT. By improving access to transplantation, transplant recipients are in better health at the time of LDLT and have better outcomes. This also results in fewer deaths on the waiting list, even for patients who do not receive a LDLT.

The authors note that “whether LDLT is a superior option in and of itself or is instead a proxy for higher volume and more experienced centers, with associated better outcomes, may not be entirely feasible to tease out from the data.”

N Galvan et al. Liver Transplantation 2025; 31: 836-839. CON: LDLT should not be a requirement for pediatric transplant programs

Galvan et al counter with their good statistics from their large-volume center in Houston. In their center, 91% of the liver transplants performed over a decade were size-matched, whole organ allografts. They attribute some of their success to their central U.S. location allowing them to access more donors without compromising warm ischemia time. Other factors that make LDLT less viable at their center include lack of Medicaid reimbursement for living donor operations (51% of their patients rely on public insurance) and concern that the donor is oftentimes a primary caregiver.

They note that most programs in U.S. “are low-volume centers, that is, <5 pediatric liver transplants/year, making up 75% of the pediatric centers in the country that account for 38.5% of the pediatric cases…Experience is garnered by volume, and so the question,…is whether it is worth consolidating small-volume programs.”

My take: LDLT is an important tool to improve outcomes. The ability to access LDLT and technical variant grafts could be life-saving for a patient. Thus, from a public policy standpoint, it would make more sense to have fewer high-volume liver transplant centers that offer these options. Centers, like Houston, which have improved organ availability/acceptance and main high-volume, are the exception and not the rule with regard to outcomes.

Related blog posts:

- What Can Go Wrong with Living Liver Transplantation for the Donor

- How to Improve the Gift of Life

- How to Lower Pediatric Liver Transplantation Waitlist Mortality

- Liver Transplant Outcomes in Children: Two Studies

- More on Time to Split (2018)

- What is Driving Racial Disparities in Access to Living Donor Liver Transplants