This blog entry has abbreviated/summarized these presentations. Though not intentional, some important material is likely to have been omitted; in addition, transcription errors are possible as well.

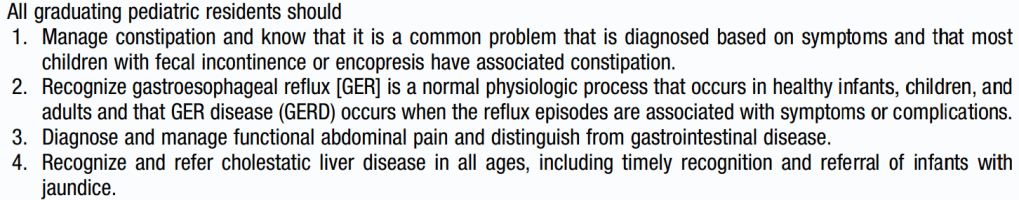

Here is a link to postgraduate course syllabus: NASPGHAN PG Syllabus – 2017

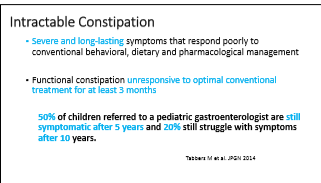

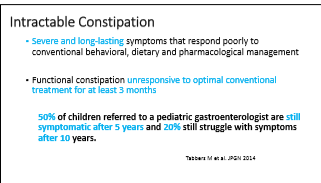

The child with refractory constipation

Jose Garza GI Care for Kids & Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta

Key points:

- Polyethylene glycol is a first-line agent and many patients require cleanout at start of therapy

- Adequate dose of laxative is needed for sure regular painless stools

- Don’t stop medicines before toilet training and until pattern of regular stooling established. “All symptoms of constipation should resolve for at least one month before discontinuation of treatment”

- Gradually reduce laxatives when improved

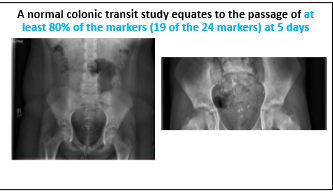

- An abdominal xray is NOT recommended to make the diagnosis of constipation

- Do you have the right diagnosis? Irritable bowel is often confused with constipation. With constipation, the pain is relieved after resolution of constipation.

- Outlet dysfunction. Stimulant laxatives (eg. Senna) are probably underutilized. Biofeedback may help in older children.

- Slow transit constipation. Newer prosecretory agents may be helpful –lubiprostone and linaclotide.

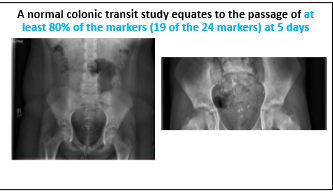

- Organic constipation. Hirschsprung’s, Spina bifida, anorectal malformations etc. Testing: anorectal manometry, rectal biopsy (for Hirschsprung’s)

- For refractory disease, consider rectal therapy –suppositories, transanal irritagations/enemas (~78% success for fecal incontinence/constipation). These treatments should be used prior to surgical therapy (eg. Malone antegrade continence enema/cecostomy)

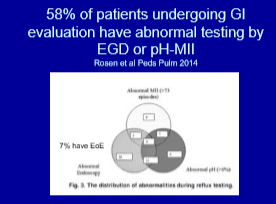

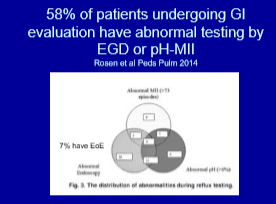

The quest for the holy grail: Accurately diagnosing and treating extraesophageal reflux

Rachel Rosen Boston Children’s Hospital

Key points:

- It is frequent that EGD or impedance study will be abnormal, though this may not be causally-related.

- No correlation with ENT exams/red airways and reflux parameters

- No correlation with lipid laden macrophages and reflux parameters

- No correlation with salivary pepsin and reflux parameters

Treatment:

- Lansoprazole was not effective for colic or extraesophageal symptoms (Orenstein et al J Pediatrics 2009)

- PPIs can increase risk of pneumonia/respiratory infections

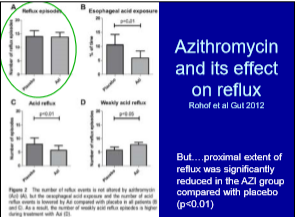

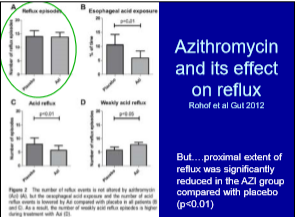

- Macrolides have been associated with increased risk of asthma but may be helpful for pulmonary symptoms

- Fundoplication has not been shown to be effective for reducing aspiration pneumonia. Fundoplication could increase risk due to worsened esophageal drainage.

- ALTEs (BRUEs -brief resolved undefined events) need swallow study NOT PPIs

POTS and Joint Hypermobility: what do they have to do with functional abdominal pain?

Miguel Saps University of Miami

Key points:

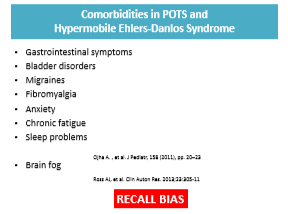

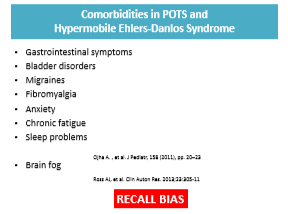

- Patients with POTS and joint hypermobility have frequent functional abdominal pain as well as other comorbidities

- Beighton Score can determine if joint hypermobility is present

- Brighton Score determines if hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos syndrome is present

- Patients with frequent fatigue. Gradual progressive and regular exercise is important part of therapy. Can start with recombant exercise – training bicycle exercise, swimming

- Need to push salt intake and fluds

Do I need to test that C.R.A.P.?

Rina Sanghavi Children’s Medical Center Dallas

This basic talk reviewed a broad range of issues related to functional abdominal pain.

Key points:

- Carnett’s sign can help establish abdominal pain as due to abdominal wall pain rather than visceral pain

- What is an appropriate evaluation? Limited diagnostic testing for most patients.

- Alarm symptoms include: Fevers, Nocturnal diarrhea, Dysphagia, Significant vomiting, Weight Loss/poor growth, Delayed Puberty, and Family history of IBD