Link: Management of Clostridium difficile Infection in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Expert Review from the Clinical Practice Updates Committee of the AGA Institute

Abstract: The purpose of this expert review is to synthesize the existing evidence on the management of Clostridium difficile infection in patients with underlying inflammatory bowel disease. The evidence reviewed in this article is a summation of relevant scientific publications, expert opinion statements, and current practice guidelines. This review is a summary of expert opinion in the field without a formal systematic review of evidence.

Best Practice Advice 1: Clinicians should test patients who present with a flare of underlying inflammatory bowel disease for Clostridium difficile infection.

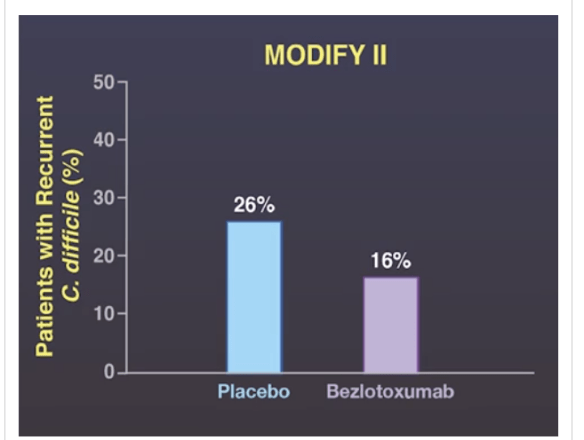

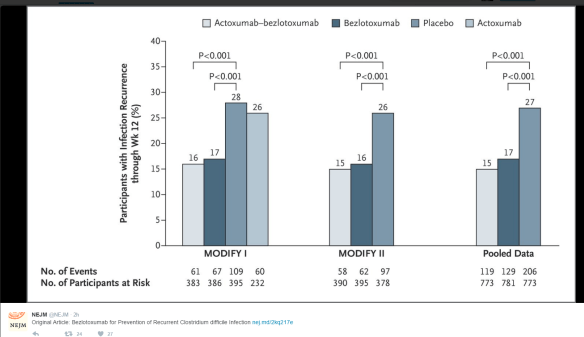

Best Practice Advice 2: Clinicians should screen for recurrent C difficile infection if diarrhea or other symptoms of colitis persist or return after antibiotic treatment for C difficile infection.

Best Practice Advice 3: Clinicians should consider treating C difficile infection in inflammatory bowel disease patients with vancomycin instead of metronidazole.

Best Practice Advice 4: Clinicians strongly should consider hospitalization for close monitoring and aggressive management for inflammatory bowel disease patients with C difficile infection who have profuse diarrhea, severe abdominal pain, a markedly increased peripheral blood leukocyte count, or other evidence of sepsis.

Best Practice Advice 5: Clinicians may postpone escalation of steroids and other immunosuppression agents during acute C difficile infection until therapy for C difficile infection has been initiated. However, the decision to withhold or continue immunosuppression in inflammatory bowel disease patients with C difficile infection should be individualized because there is insufficient existing robust literature on which to develop firm recommendations.

Best Practice Advice 6: Clinicians should offer a referral for fecal microbiota transplantation to inflammatory bowel disease patients with recurrent C difficile infection.

Related blog posts:

- Overdiagnosis of Clostridium difficile with PCR Assays

- Clostridium difficile/Fecal Microbiota Transplantation Video …

- Clostridium difficile: Colonization vs. Symptomatic Infection …

- Clostridium difficile Epidemiology | gutsandgrowth

- Precise Identification of C difficile Transmission …

- Clostridium difficile in IBD | gutsandgrowth

- A C difficile two-fer | gutsandgrowth

- Keeping Up with Clostridium Difficile | gutsandgrowth

- How Common are Clostridium difficile infections …

- Predicting Severe Clostridium Difficile | gutsandgrowth

- Consensus Guidelines on FMT | gutsandgrowth