Another study has shown the potential for probiotics to help colicy infants. In an editorial, Carlos Lifschitz sums up the paper (The Journal of Pediatrics Volume 163, Issue 5 , Pages 1250-1252, November 2013); here is an excerpt (link from Kipp Ellsworth twitter feed —goo.gl/b3iMFu):

For reasons that are not clear, human infants are born with a well-developed capacity to cry.1 …Unexplained and severe crying affects 3%-28% of breastfed or formula-fed (otherwise-healthy) young infants.2 Although excessive, inconsolable crying and colic are considered to be a benign, self-resolving problem, they can be very distressing and lead to marital conflict and parental exhaustion.3 Infantile colic is defined as paroxysmal, excessive, inconsolable crying without an identifiable cause in an otherwise-healthy infant occurring in the first 3 months of life and lasting a minimum of 3 hours per day, 3 days per week, for 3 weeks…

Enter probiotics. Lactobacillus reuteri DSM 17 938 at a dose of 108 colony-forming units per day in breastfed infants improved symptoms of infantile colic,19 a finding that was further corroborated.20 Despite evidence that altering the microbiota may result in reduced crying, the physiopathology still remains unclear…

In this issue of The Journal, Pärtty et al22 attempt to prevent excessive crying in former premature infants….To determine whether excessive crying is preventable by manipulation of intestinal microbiota, 94 preterm infants, some breast- and formula-fed, with gestational ages ranging from 32 to 36 weeks and birth weights >1500 g, were randomized in the first 3 days of life in a double-blind study to receive for the following 2 months either a mixture of galacto-oligosaccharide and polydextrose (prebiotic group), Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG (probiotic group), or placebo…Follow-up consultations were conducted by the same study nurse at the age of 1, 2, 4, 6, and 12 months…

Significantly less frequent crying was observed in both the pre- and probiotic groups compared with the placebo group (19% vs 19% vs 47%, respectively; P = .02). At 1 month of age, the infants’ fecal microbiota were investigated. The proportion ofLactobacillus-Lactococcus-Enterococcus group to total bacterial count and the proportion of Clostridium histolyticum group to total bacterial count was greater in excessive criers than in contented infants in all 3 study groups (pre-, probiotics, and placebo). The authors concluded that early pre- and probiotic supplementation may alleviate symptoms associated with crying and fussing in preterm infants.

Although in the study the following associations did not reach statistical significance, they are of interest for future investigation: contented infants were more often exclusively breast-fed during the first 2 months (42% vs 22%, respectively, P= .09) and their mothers had received perinatal antibiotics less often (22% vs 41%, respectively, P = .07) than criers… Contrary to this hypothesis, however, is the finding that persistent criers were more often born by vaginal delivery as opposed to cesarean delivery (81% vs 63%, P = .07) than contented babies. This finding is surprising because birth by cesarean delivery and, therefore, lack of exposure to the microbiota of the vaginal canal and perineum, has been associated with abnormal development of intestinal microbiota and several diseases.

Related blog posts:

In a video, Dr. Sanjay Gupta and Dr. John Bachman say ‘we don’t know why babies have colic, but it will end and is not the parent’s fault:’ ow.ly/q4IsW

Disclaimer: These blog posts are for educational purposes only. Specific dosing of medications (along with potential adverse effects) and specific medical interventions should be confirmed by prescribing physician. Application of the information in a particular situation remains the professional responsibility of the practitioner.

Additional references:

- -Pediatrics 2010; 126: e526. Double-blind randomized placebo-controlled trial of Lactobacillus reuteri.

- -J Pediatr 2009; 155:823. Increased calprotectin in colicy infants. n=36. editorial pg 772.

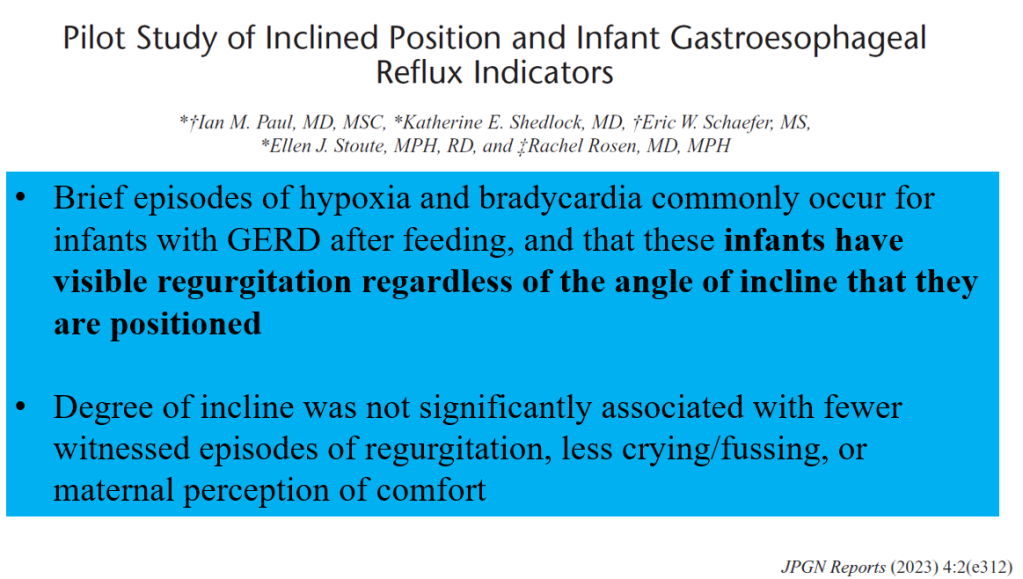

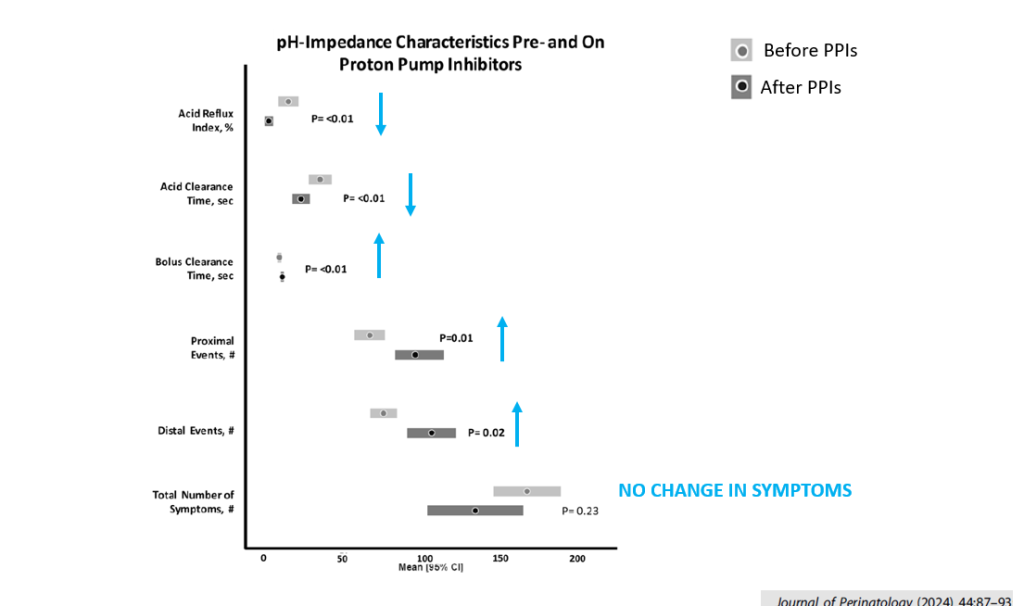

- -J Pediatr 2009; 154: 514-20. Colic and reflux. (Orenstein et al), & 475 (editorial -Putnam). PPIs (lansoprazole) do not help colicy Sx in infants c GERD. n=162. Increased resp infections in pts on PPIs. 44% response in Rx & control group.

- -J Pediatr 2008; 152: 801. Probiotic helped reduce colic sx in 30 preterm infants, Lactobacillus reuteri

- -Pediatrics 2007; 119; e124. Probiotics reduced colic in breastfed babies more than simethicone. n=83, lactobacillus reuteri, 10-8th power per day. Decreased crying 18 minutes per day at 1 week compared to simethicone & by 94 minutes/day at 4 weeks (95% response vs 7% of simethicone)

- -Pediatrics 2005; 116: e709. Low-allergen maternal diet was helpful.

- -Hochman JA, Simms C: “The role of small bowel bacterial overgrowth in infantile colic“J Pediatr 2005; 147: 410-411 (Letter to Editor).

- -Arch Pediatr Adol Med 2002; 1183 &1172. lack of sequelae on maternal mental health.

- -Arch Pediatr Adol Med 2002; 156: 1123-1128. colic 24% of infants, breastfeeding did not help.

- -Pediatrics 2002; 109: 797-805. carbohydrate malabsorption with breath testing in colicy infants, n=30. 2 hour fasting period.