WL Hasler et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2024; 22: 867-877. Open Access! Benefits of Prokinetics, Gastroparesis Diet, or Neuromodulators Alone or in Combination for Symptoms of Gastroparesis

Methods: In this prospective study of patients (n=129) with suspected gastroparesis, the authors examined longitudinal outcomes focusing on responses to prokinetics and other therapies. This included gastroparesis diets and neuromodulators. Patients underwent validated gastric emptying testing (wireless motility capsule and gastric emptying scan) before recommending new treatments.

Prokinetics included dopamine antagonists, motilin agonists, acetylcholinesterase

inhibitors, and pyloric botulinum toxin injection.

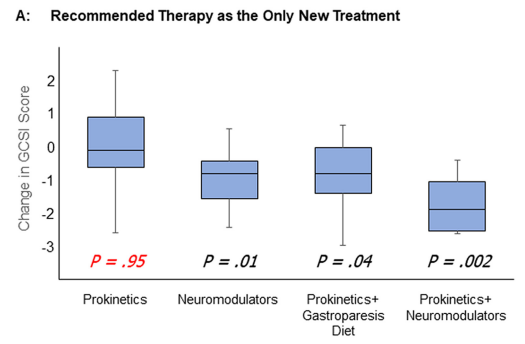

Key findings:

- “Initiating prokinetics as solo new therapy had little benefit for patients with symptoms of

gastroparesis.” - “Neuromodulators as the only new therapy decreased symptoms other than

nausea and vomiting” - Combination therapy of a prokinetic with a neuromodulator appeared to be the most effective

- Neuromodulators were mainly effective in those without delayed gastric emptying times

My take: Our therapies for gastroparesis are not very good. And, neuromodulators are likely to be more helpful than prokinetics.

Example of a gastroparesis diet: Cleveland Clinic Gastroparesis Diet (7 pages). Part of the diet recommendations are shown below.

Related blog posts:

- A Treatment For Gastroparesis with a 30% Response: Placebo

- Gastroparesis is Frequently Misdiagnosed

- If a Gastroparesis Medication Works in the Forest But No One Sees It, Did It Really Work?

- Neuromodulators & Gastroparesis (Bowel Sounds Episode)

- Are Gastroparesis and Functional Dyspepsia Part of the Same Problem?

- Tweetorial: Refractory Gastroparesis

- Dreaded Nausea (2022) Plus Skills or Pills

- Epidemiology of Gastroparesis in Adults