A recent Hepatology issue with reviews on cholestatic diseases featured three articles focused on Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis (PSC). These in-depth reviews spanned ~60 pages with more than 500 references.

TH Karlsen et al. Hepatology 2025; 82: 927-948. Open Access! Medical treatment of primary sclerosing cholangitis: What have we learned and where are we going?

As an aside, all of the articles include a short AI-generated plain language summary. I am a little surprised that the journal put in a disclaimer for them: “Text is machine generated and may contain inaccuracies.” The authors and editors have the expertise to assure accuracy of the summary of their published article. (I am the one who needs a disclaimer.)

A Few Points:

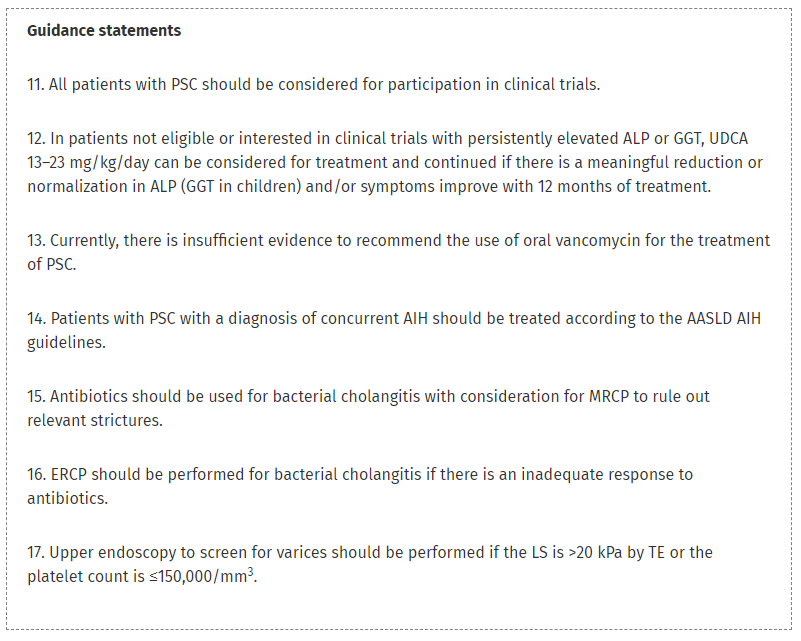

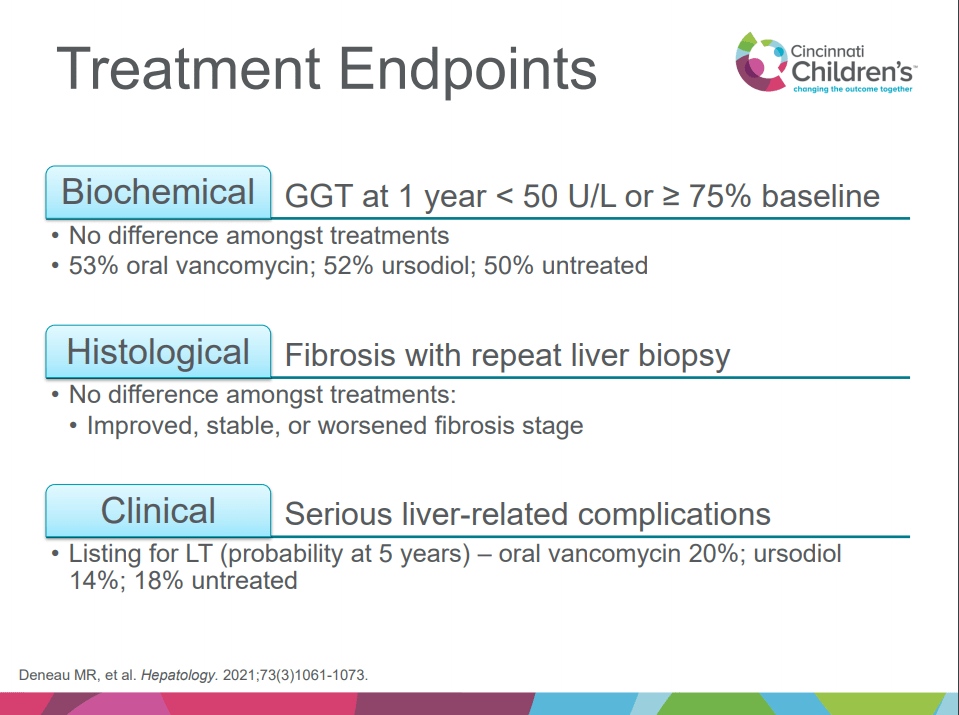

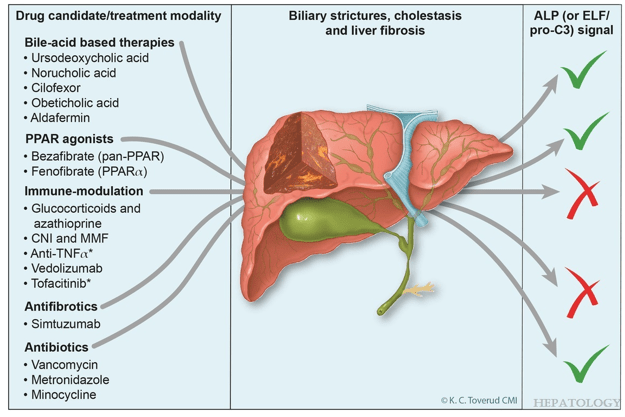

- “It has proven difficult to establish robust evidence for significant clinical benefits of medical treatment in primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC). For ursodeoxycholic acid, clinical practice guidelines only offer vague recommendations”

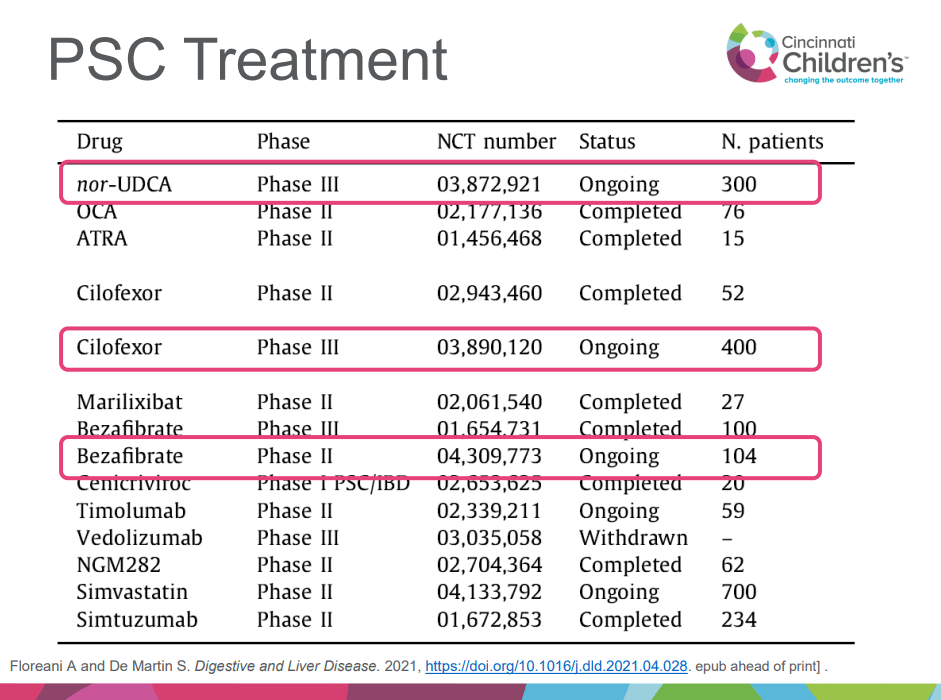

- “Norucholic acid (previously denominated nor-UDCA) is a side chain–shortened homologue of UDCA that has shown superior anticholestatic, anti-inflammatory, and antifibrotic properties compared to UDCA in animal models.9 In PSC, norucholic acid was compared to placebo in a randomized multicenter phase II trial that evaluated the safety and efficacy of 12 weeks of treatment with oral norucholic acid (500, 1000, or 1500 mg/d) compared with placebo.10 … Norucholic acid significantly reduced ALP values in all treatment arms compared to placebo, and the safety profile was comparable across groups…An ongoing phase III placebo-controlled study compares oral treatment with 1500 mg/d norucholic acid with placebo on PSC disease progression assessed by a decrease in ALP and liver histology as a combined primary endpoint (NCT03872921)”

- Other therapies are reviewed in depth

- R Kellermayer et al. Hepatology 2025; 82: 949-959. Open Access! Identifying a therapeutic window of opportunity for people living with primary sclerosing cholangitis: Embryology and the overlap of inflammatory bowel disease with immune-mediated liver injury This article examines age-dependent variation in presentation and theorizes that “there may be a particularly receptive window of opportunity to treat PSC, most likely during pre-pubertal development, before significant fibrosis and biliary obstruction occur”

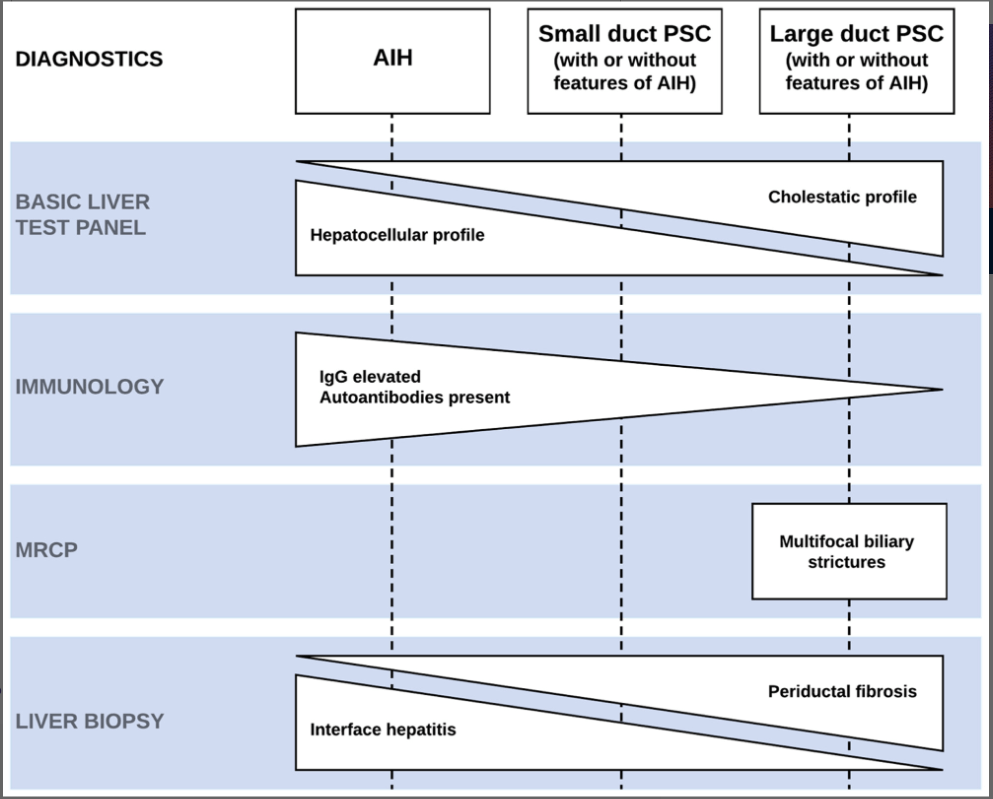

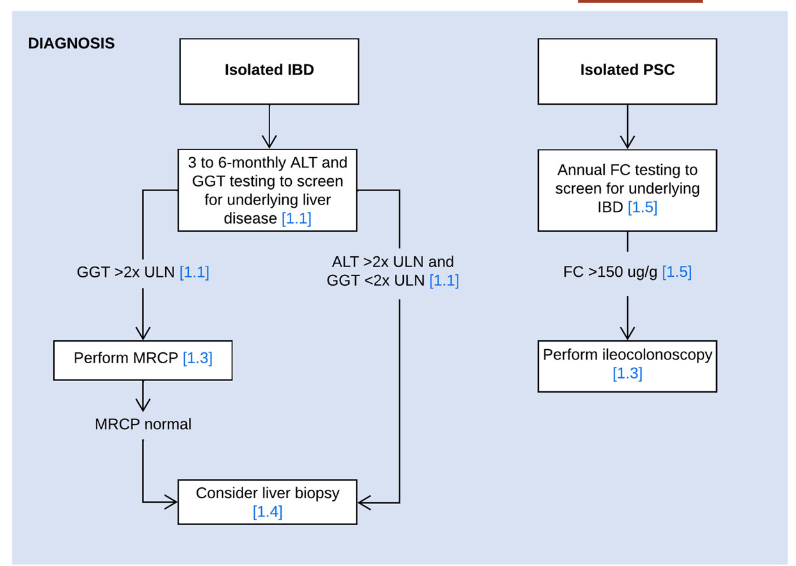

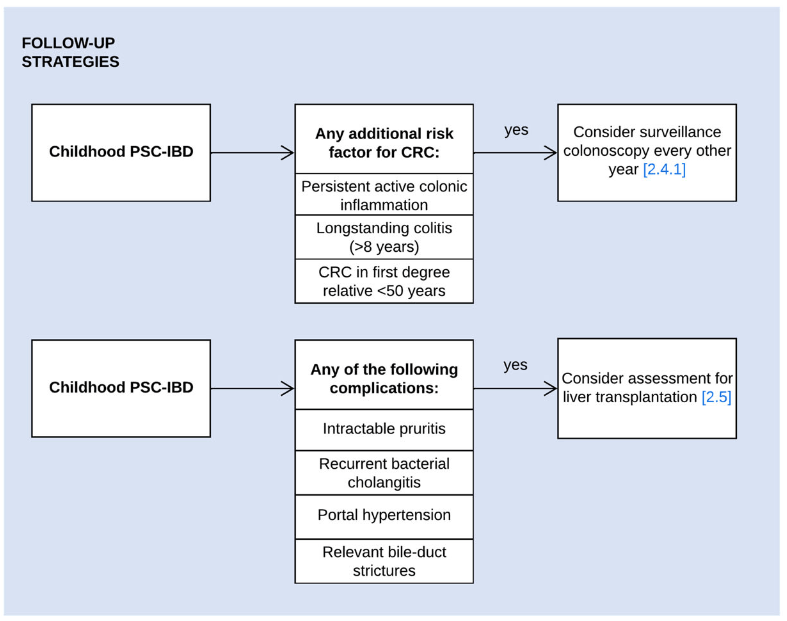

- LJ Horst et al. Hepatology 2025; 82: 960-984. Open Access! PSC and colitis: A complex relationship “The clinical phenotype, genetic, and intestinal microbiota associations strongly argue for PSC-IBD being a distinct form of IBD, existing alongside ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. In fact, the liver itself could contribute to intestinal pathology, clinically overt in 60%–80% of patients. Recent studies suggested that on a molecular level, almost all people with PSC have underlying colitis…complex pathophysiological relationships, where factors such as genetic predisposition, changes in the intestinal microbiota, altered bile acid metabolism, and immune cell migration are among the suspected contributors.”

My take: These are good reviews that highlight how much we have learned about PSC but also details the challenges ahead.

Related blog posts:

- ESPGHAN Guidelines for PSC in Children

- Cholangiocarcinoma Risk in Pediatric PSC-IBD Plus one

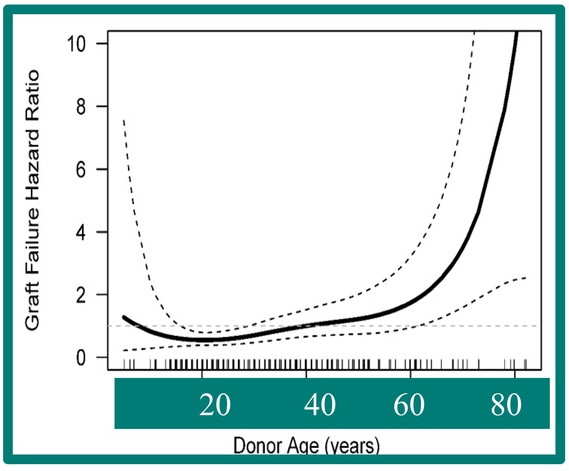

- Liver Transplantation for PSC: Long-term Outcomes and Complications

- Favorable Phase II Study of Cilofexor for Patients with PSC

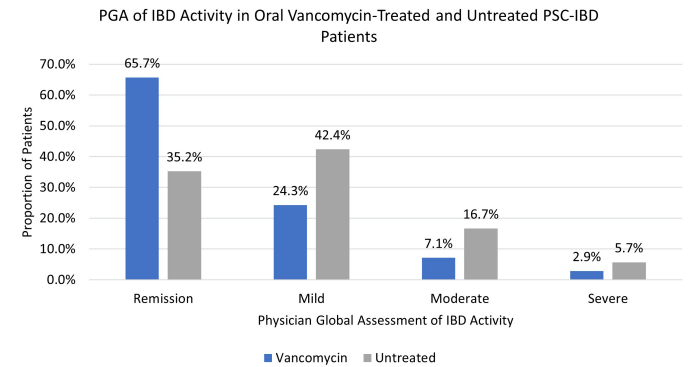

Vancomycin for Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Patients with Primary Sclerosing Cholantgitis - PSC in IBD

- Recurrent PSC in Children After Liver Transplantation

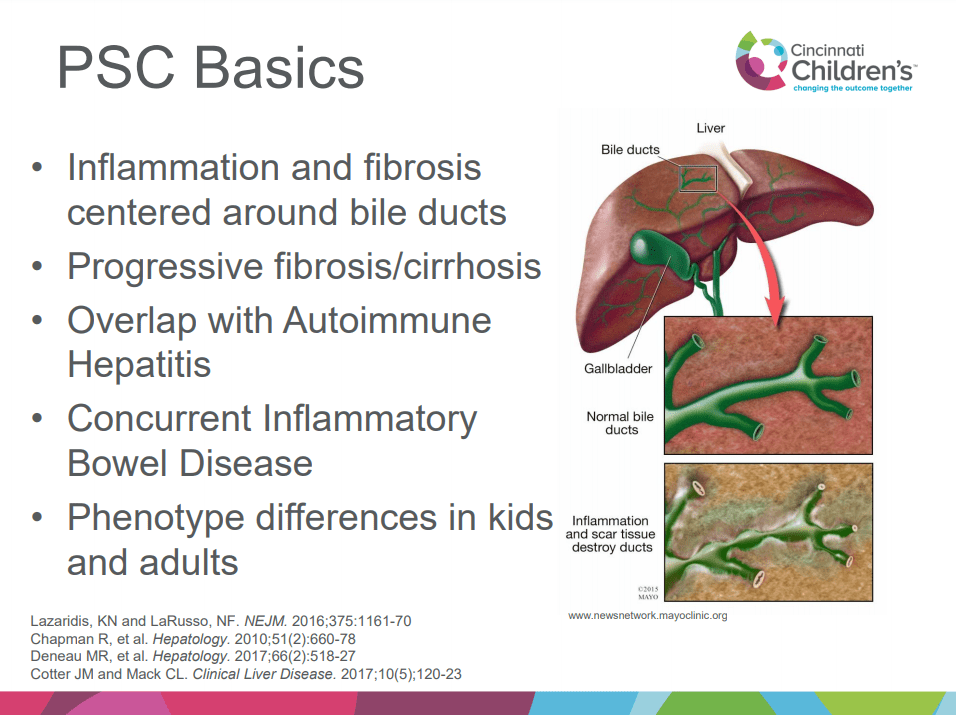

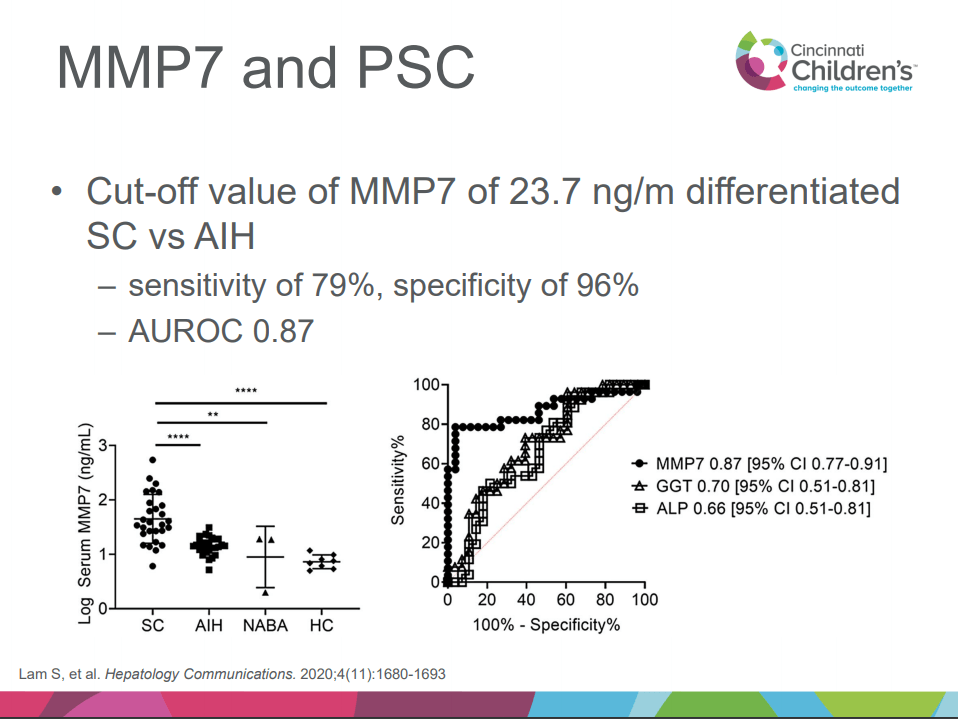

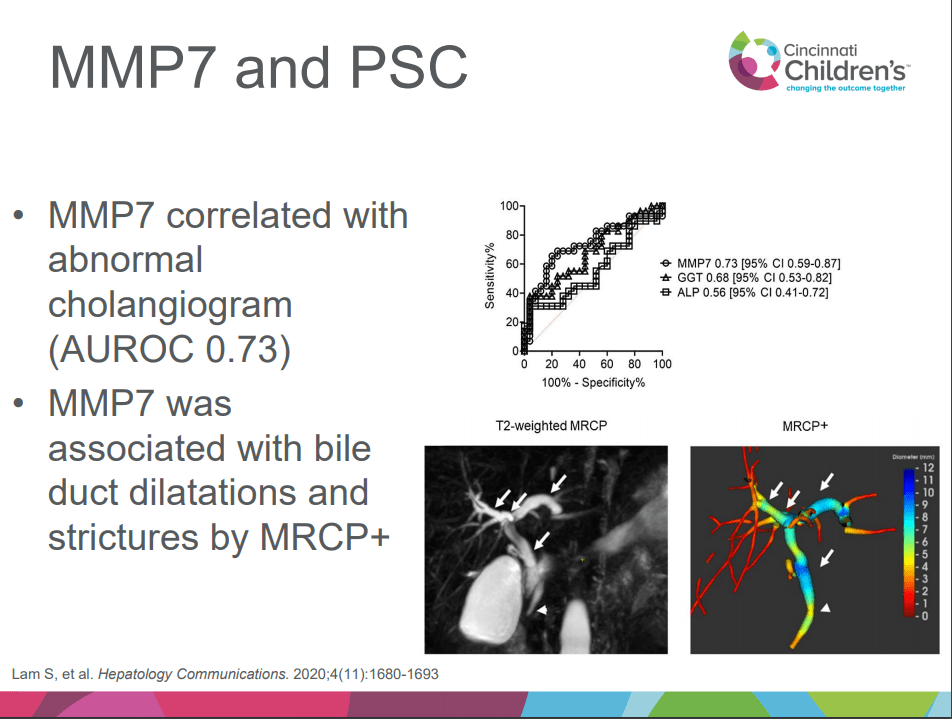

- Aspen Webinar 2021 Part 5 -Autoimmune Liver Disease & PSC 2021. This lecture highlights studies show lack of efficacy with vancomycin, ursodeoxycholic acid and vedolizumab in altering the liver disease. Also, there is potential utility of MMP-7 for distinguishing between PSC and AIH

- Liver Problems with Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- Active Colitis More Likely in Children with PSC-IBD

- Big Study of PSC in ChildrenPSC -Natural History Study (pediatric)

- Should We Care About Subclinical Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis with Inflammatory Bowel Disease?

- Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis (PSC) –Natural History Study

Disclaimer: This blog, gutsandgrowth, assumes no responsibility for any use or operation of any method, product, instruction, concept or idea contained in the material herein or for any injury or damage to persons or property (whether products liability, negligence or otherwise) resulting from such use or operation. These blog posts are for educational purposes only. Specific dosing of medications (along with potential adverse effects) should be confirmed by prescribing physician. Because of rapid advances in the medical sciences, the gutsandgrowth blog cautions that independent verification should be made of diagnosis and drug dosages. The reader is solely responsible for the conduct of any suggested test or procedure. This content is not a substitute for medical advice, diagnosis or treatment provided by a qualified healthcare provider. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a condition.