A recent issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology focused solely on the clinical features and management of inflammatory bowel disease. Even for those with expertise in IBD, there is a lot of useful information and concise reviews of what is known.

Here are some of my notes from this issue (part 3):

RP Hirten et al. Clinical Gastroenterol Hepatol: 2020; 18: 1336-45. A User’s Guide to De-escalating Immunomodulator and Biologic Therapy in Inflammatory Bowel Disease

This article emphasizes the need for assessment of bowel disease activity before attempting de-escalation and provides a list of risk factors for flare-up off therapy.

Some of the Risk factors for Disease Flare with De-escalation:

- Disease activity/abnormal biomarkers (CRP, WBC, Hemoglobin, Calprotectin)

- Perianal disease

- Penetrating disease

- Extensive disease involvement

- Abnormal bowel wall thickening on MRE

- Young age at diagnosis

- Short treatment duration

- Prior surgeries

Key points:

- In individuals on combination therapy, dropping immunomodulator therapy (but not biologic therapy) did NOT increase the short term risk of a flare up in a recent Cochrane review. However, this did impact anti-TNF kinetics and lowers anti-TNF troughs.

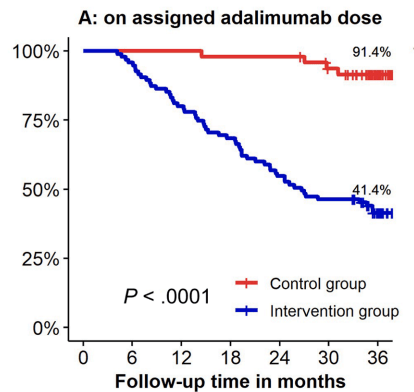

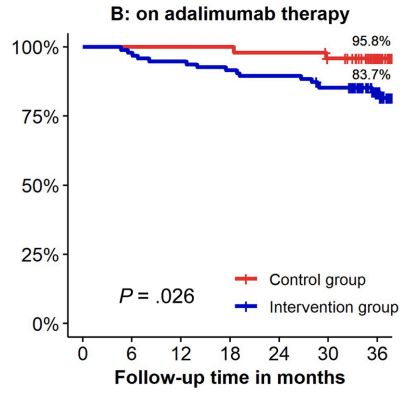

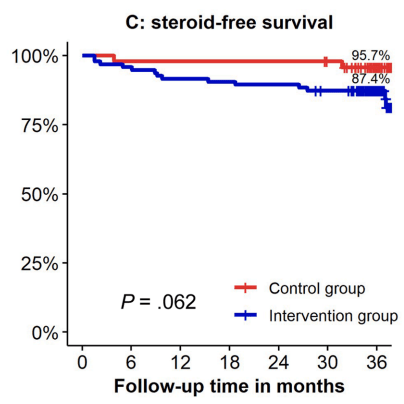

- With regard to stopping biologics, among patients in deep remission, the authors advise counseling patients (CD and UC) that stopping biologic agents results in a “40-50% relapse over the following 2 years that will further increase over time.”

- Careful followup is recommended if a patient elects to stop biologic therapy. “CD and UC are progressive relapsing conditions…and approximately 80% of subjects” require re-initiation of biologic therapy with 7 years.”

- “Repeat colonoscopy or imaging should be performed if a significant change in symptoms occurs or abnormal biomarkers are detected.”

- In patients who resume infliximab, the authors advocate for an initial induction of 0, 4, and 8 weeks. The presence of antidrug antibodies at week 2 “precludes drug administration and alternative agent should be started.”

Related blog posts:

M Kaur et al Clinical Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020; 18: 1346-55. Inpatient Management of Inflammatory Bowel Disease-Related Complications

This article reviews the approach to acute severe ulcerative colitis which has been discussed recently on this blog post and offers management recommendations for complications related to Crohn’s disease including abscesses, strictures/bowel obstruction. With regard to abscess management, the authors note that medical therapy is more likely to be effective in those with a first-time abscess, spontaneous origin, right lower quadrant location, and smaller abscess size (<3 cm). Stricture with upstream dilatation of bowel, multi-loculated abscesses and steroid use are features that make therapy less likely to be successful.

Related blog posts -ASUC:

Abscess-related blog posts:

EL Barnes et al Clinical Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020; 18: 1356-66. Perioperative and Postoperative Management of Patients With Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis

This article reviews risk factors for disease recurrence after surgery, presurgical management (eg. minimize steroids, improve nutrition, do not delay surgery based on preoperative biologic exposure), postoperative strategies and management of pouchitis.

- In those at high risk for postoperative disease recurrence, the authors advocate anti-TNF therapy plus an immunomodulator with colonoscopy at 6-12 months. In those at low risk, many are placed on no medications and have a colonoscopy at 6 months postoperatively.

- The section on pouchitis lists alternatives to metronidazole and ciprofloxacin if these lose efficacy. This includes amoxicillin-clavulanate, sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim, doxycycline and vancomycin.

- Related blog post: What’s Going on With Pouchitis?

S Singh et al Clinical Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020; 18: 1367-80. Management of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases in Special Populations: Obese, Old, or Obstetric

A Levine et al Clinical Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020; 18: 1381-92. Dietary Guidance From the International Organization for the Study of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases

- The authors recommend more vegetables and fruits with CD (but low insoluble fiber if stricture present)

- “Prudent to reduce intake of red and processed meat” with UC

- “Prudent to increase dietary omega-3 fatty acids” from marine fish but not from dietary supplements with UC

- ‘Prudent to use a low FODMAP diet for patients with persistent symptoms for CD and UC despite resolution of inflammation’

M Collins et al Clinical Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020; 18: 1393-1403.Management of Patients With Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor-Induced Enterocolitis: A Systematic Review

This study reviews colitis induced by immune checkpoint inhibitors which are similar to young patients with inherent CTLA4b deficiency.

Related blog posts:

Disclaimer: This blog, gutsandgrowth, assumes no responsibility for any use or operation of any method, product, instruction, concept or idea contained in the material herein or for any injury or damage to persons or property (whether products liability, negligence or otherwise) resulting from such use or operation. These blog posts are for educational purposes only. Specific dosing of medications (along with potential adverse effects) should be confirmed by prescribing physician. Because of rapid advances in the medical sciences, the gutsandgrowth blog cautions that independent verification should be made of diagnosis and drug dosages. The reader is solely responsible for the conduct of any suggested test or procedure. This content is not a substitute for medical advice, diagnosis or treatment provided by a qualified healthcare provider. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a condition.