MR Curtis et al. Pediatrics (2025) 155 (5): e2024068565. Disparities in Linkage to Care Among Children With Hepatitis C Virus in the United States

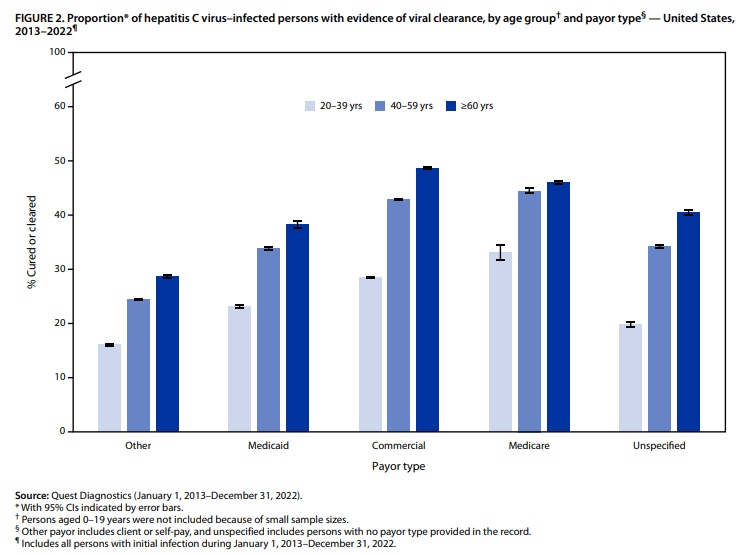

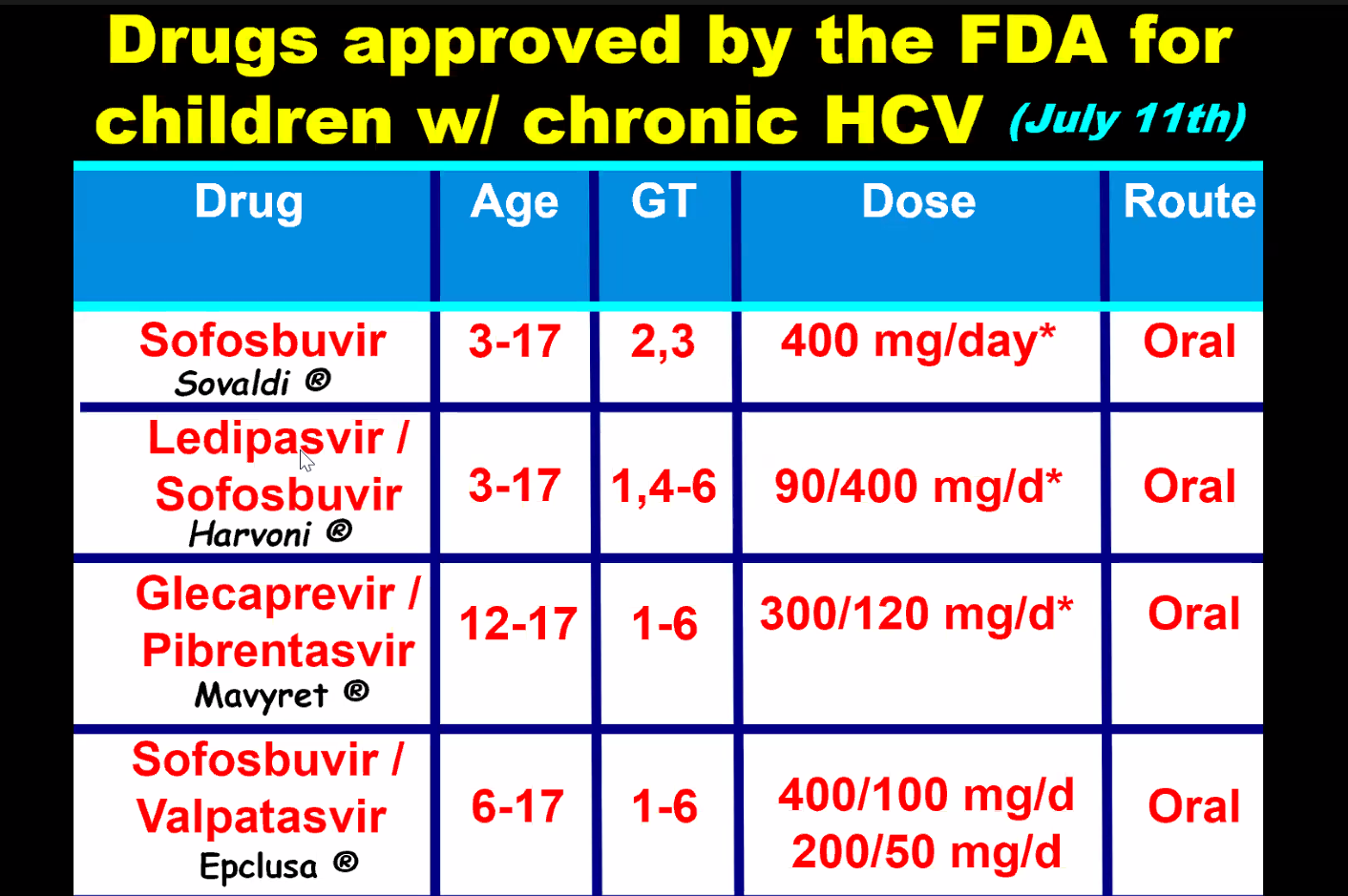

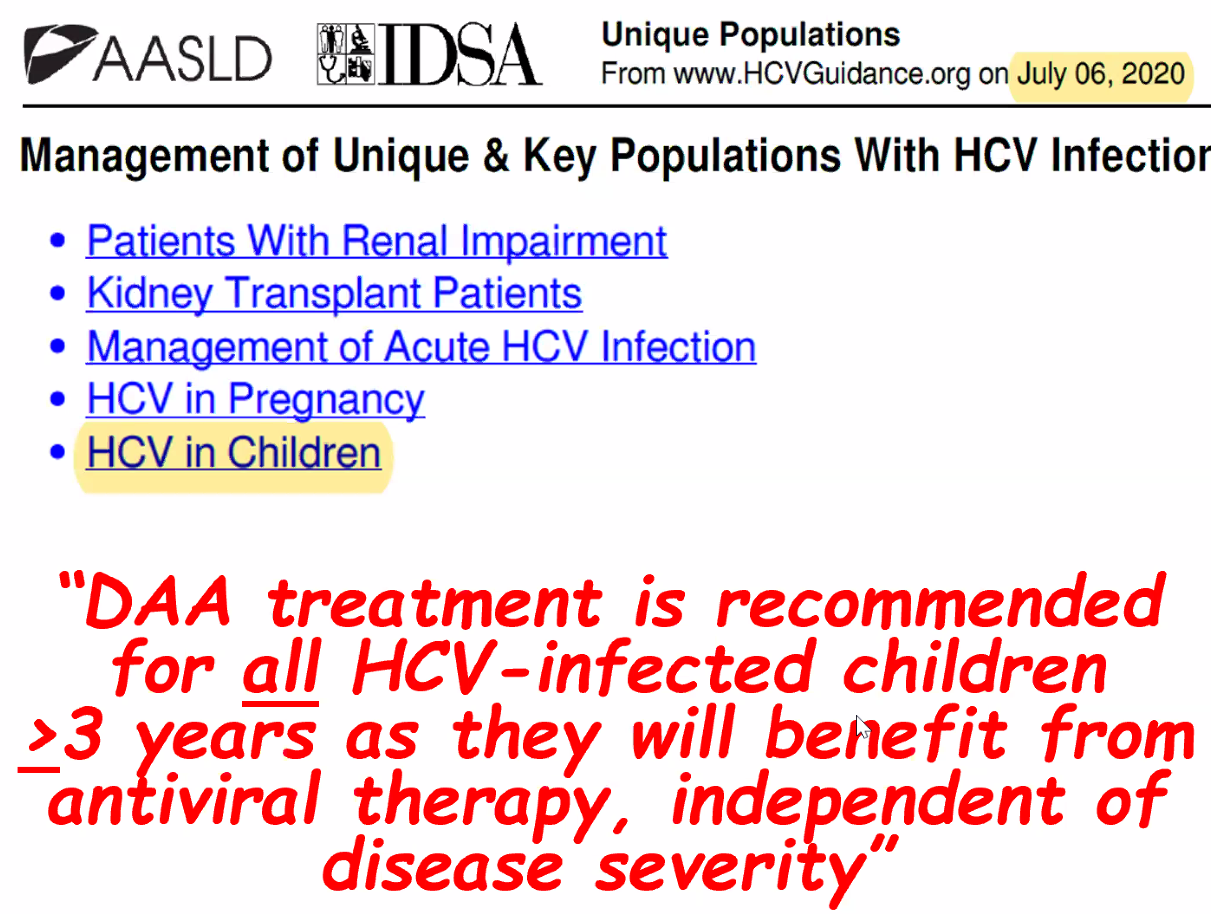

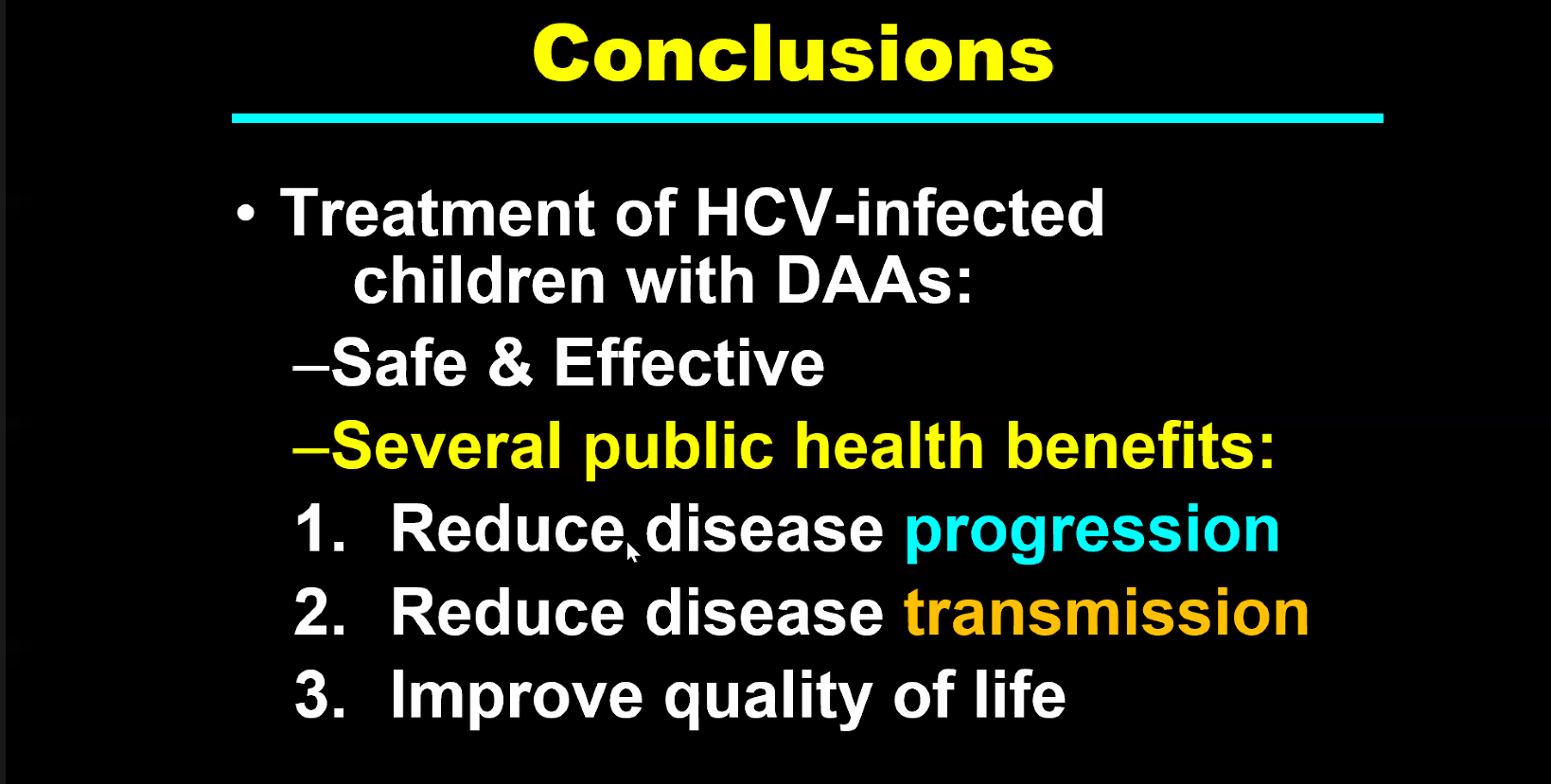

Background: “Current guidelines recommend treating all children aged 3 years or older with DAAs (direct-acting antivirals). These treatments achieve cure in more than 98% of HCV cases and reduce risks for cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), and liver-related mortality. Despite availability of DAAs, only 62% of adults with HCV have linked to care, 39% initiated treatment, and 26% attained cure (sustained virologic response) as of 2023.”

Methods: This retrospective cohort analysis included children born between 2000 and 2018 who were diagnosed with HCV between the ages of 0 and 18 years. The study analyzed TriNetX Research Network data, a US national electronic health records network with more than 87 million individuals within the U.S.

Key findings:

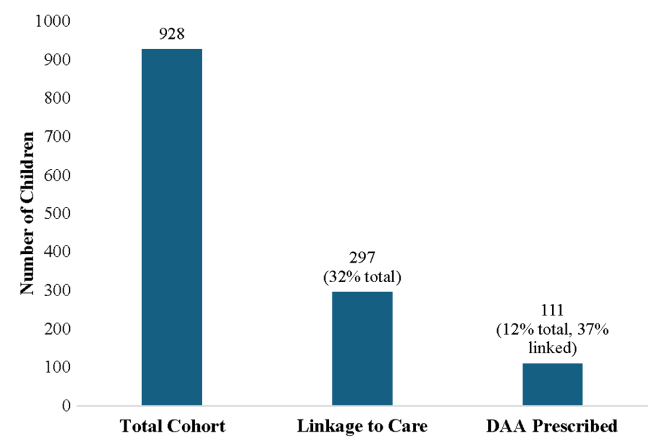

- Among 928 children with HCV, 297 (32.0%) linked to HCV care and 111 (12.0%) were prescribed a DAA (direct-acting antiviral). Thus only 1 in 8 children with HCV were prescribed DAAs

- Of 928 children with HCV, 35.9% of children were diagnosed with HCV perinatally (by 3 years old), 44.5% during childhood (between 4 and 12 years old), and 19.6% in adolescence (between 13 and 18 years old)

- White and Hispanic/Latinx children were much more likely than black children to receive a DAA prescription with OR of 3.44 and 2.20 respectively

- Children in Midwest, North, and West had higher rights of DAA prescription compared to the South with OR of 2.40, 1.50, and 4.19 respectively

Discussion points:

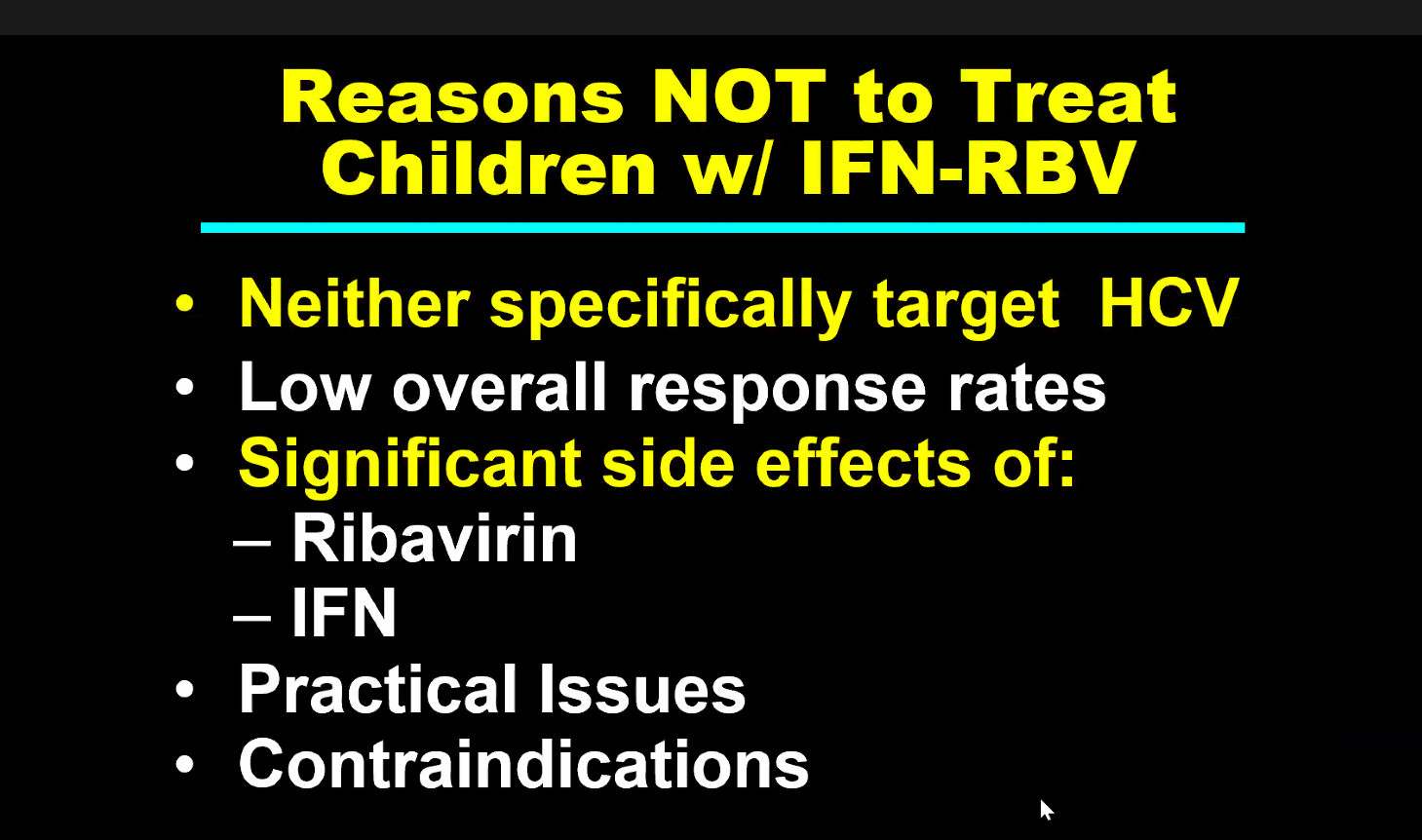

Potential barriers to treatment:

- DAAs were only approved for children aged 3 years or older in 2019 for some genotypes and not until 2021 for all genotypes.

- Some parents choose to wait to treat young children because of difficulty administering medications at the ages of 3 and 4 years old

- Insurance: “The cause of low uptake of treatment is likely multifactorial: Medicaid and commercial insurers implemented restrictions based on degree of liver fibrosis, active or recent substance use, or specialty prescribing because of the very high initial cost of DAAs. Although most of these restrictions have now been removed, some still remain, and some insurance plans have varying criteria for pregnant or pediatric members.”

New CDC Recommendations: “In light of the new Centers for Disease Control and Prevention perinatal HCV testing recommendations and universal HCV screening recommended in pregnancy, more young children with HCV will be identified”

Limitations: Retrospective study relies on data from a database

My take: Being able to cure HCV with DAAs has been an incredible medical achievement. However, efforts to eradicate HCV have not gotten very far and had a severe setback with the opioid epidemic which increased rates of HCV. This study shows that very few children with HCV actually receive curative treatment. Advancing the goal of HCV elimination will require sustained efforts to get those identified with HCV to treatment, both in children and adults.

Related summary article in GI Hep News (5/21/25): Clinicians Can Prescribe the Cure for Hepatitis C: Most Kids Never Get It. Two other points:

- “The prevalence of HCV in pregnant people jumped 16-fold between 1998 and 2018 to 5.3 cases per every 1000 pregnancies, and these patients can transmit the disease perinatally. Many people are unaware they are infected.”

- “More than half of children clear the infection on their own by age 3, the age at which treatment can also begin”

Related blog posts:

- Why CDC is Drafting New Guidelines for Screening Children for Perinatally-Acquired Hepatitis C Infection

- NPR: Children Missing Out on Hepatitis C Treatment

- Liver Briefs: MASLD with T1DM, ESPGHAN Pediatric HCV Recommendations, Age of Kasai in Europe

- The Dark Cloud Inside the Silver Lining -What’s Really Going on with Hepatitis C Infection

- NOT Screening At-Risk Infants for Hepatitis C

- Online Aspen Webinar (Part 4) -How to Treat Hepatitis C in Children

- Medical Progress: Toward Hepatitis C Elimination

- Resolution: Eradication of Hepatitis C

- Hepatitis C in 2020: NASPGHAN Position Paper

Useful website:: HCVguidelines.org (living online reference of HCV therapies for all populations, including children)