In July, this blog reviewed a recent big study of primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) in adults with more than 7000 patients. A recent study in the pediatric age group enrolled 781 children from 36 institutions: MR Deneau et al. Hepatology 2017; 66: 518-27 (Congratulations to Nitika Gupta and Miriam Vos -in-town colleagues and contributing authors to this study.)

This retrospective study’s key findings:

- Median age 12 years at diagnosis; 39% were female

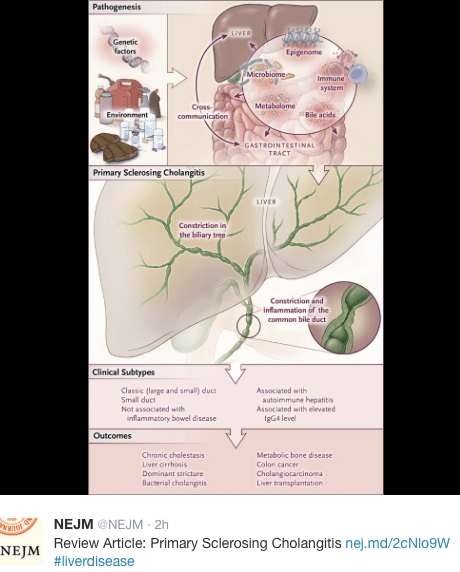

- Autoimmune hepatitis (overlap) was present in 33%

- Small-duct PSC was present in 13%

- Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) was present in 76%

- PSC-IBD and Small-duct PSC (normal cholangiograms) had more favorable prognosis with hazard ratio of 0.6 of developing complications

- Portal hypertensive and biliary complications were noted in 38% and 25% respectively. After developing these complications, the median survival with native liver was 2.8 years and 3.5 years respectively

- Survival with native liver was noted in 70% at 5 years and 53% at 10 years

- Elevations in bilirubin, GGT, and AST-to-platelet count ratio were associated with highest risk of progressive disease.

- Cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) developed in 1% (median, 6 years after diagnosis)

The discussion notes that while pediatric PSC is a progressive disease, complications were slower to develop compared with adult-onset PSC. 10-year survival with native liver is typically lower in adults ~60% (vs 70% in this study). “Up to one third of adults with PSC may have esophageal varices within a year of diagnosis” compared with only 13% in this cohort. Dominant strictures are more common in adults, occurring in the majority within 5 years whereas this occurred in 16% of this cohort.

With regard to CCA, the authors note that current recommendations suggest starting to screen for CCA in patients over age 18 years with ultrasound and CA 19-9 at 6-12 month intervals. These studies “could reasonably be extended to PSC patients aged 15 and above and [for those requiring dilatation] of biliary strictures.”

My take: This large pediatric PSC study provides more clarity on the outcomes of patient’s with PSC and the associated conditions.

Related blog posts:

- Should we care about subclinical PSC? (This post has links to others related to PSC)

- PSC -Natural History Study (pediatric)