From Gastroenterology & Endoscopy News July 2016: Tofacitinib Effective in Refractory and Severe UC

An excerpt:

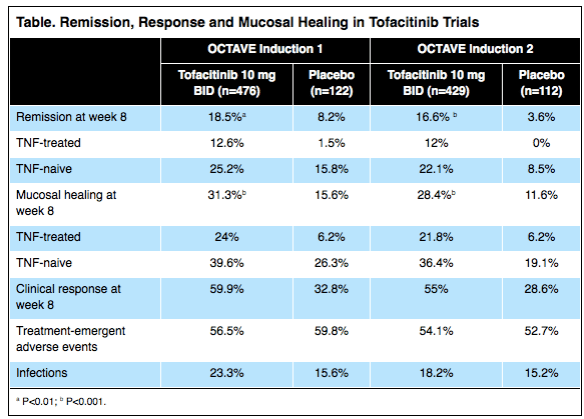

Tofacitinib (Pfizer), an oral agent already approved for certain patients with rheumatoid arthritis, can induce clinical remission in up to 25% of individuals with moderate to severe, refractory ulcerative colitis (UC) and clinical response in as many as 60% of these patients.

The results, based on two placebo-controlled trials involving more than 1,100 patients, showed the drug also increased the risk for serum lipid elevations but was otherwise safe. Researchers presented the data at the 2016 annual meeting of the European Crohn’s and Colitis Organization (ECCO; oral presentation 019)…

The new data are from the OCTAVE Induction 1 and Induction 2 trials, identically designed, randomized, double-blind and placebo-controlled Phase III studies…In the OCTAVE 1 trial, 476 patients received 10 mg of tofacitinib orally twice daily for eight weeks and 122 received an oral placebo. In OCTAVE 2, 429 and 112 patients were randomized to receive the two regimens, respectively.

Also from Gastroenterology & Endoscopy News August 2016: Update on Diagnosis and Treatment for Ulcerative Colitis This article provides a succinct summary regarding diagnosis and treatments of ulcerative colitis; treatments discussed include emerging therapies like tofacitinib.