- MD Kapelman et al. Gastroenterol 2025; 168: 980-982. Prevalence of Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease in the United States: Pooled Estimates From Three Administrative Claims Data Sources

- EI Benchimol, M Oliva-Hemker. Gastroenterol 2025; 168: 851-853. (Editorial) Open Access! Burden and Social Determinants of Health in Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Lessons Learned From Epidemiologic Studies Using Health Administrative Data

From editorial (which is more expansive than the study):

Kappelman et al4 report the US prevalence of pediatric-onset IBD (diagnosed before the age of 20 years by a physician) as well as rates of disease based on race and ethnic background. To ensure that a representative population was captured, they combined multiple health administrative databases…

The authors report that the US currently has a pediatric IBD prevalence of 125 per 100,000 population, increased from 110 per 100,000 in 2011. This is higher than previously reported in Canada (82 per 100,000 in 2023)6 and Sweden (75 per 100,000 in 2010).7 These differences may be due to the older age cutoff used in the US data, <20 years vs <18 years in the Canadian and Swedish studies. However, misclassification bias may also play a role...

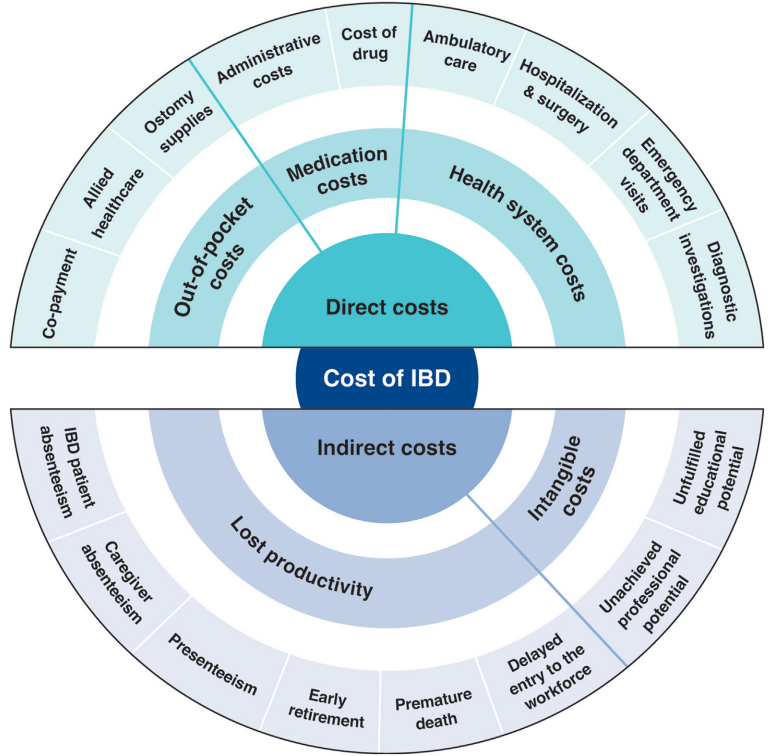

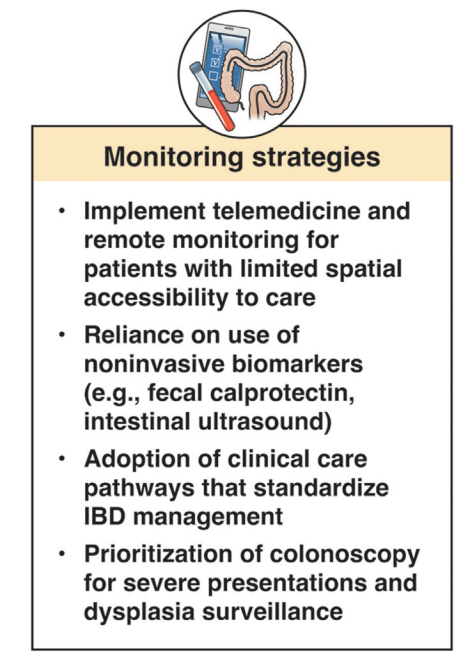

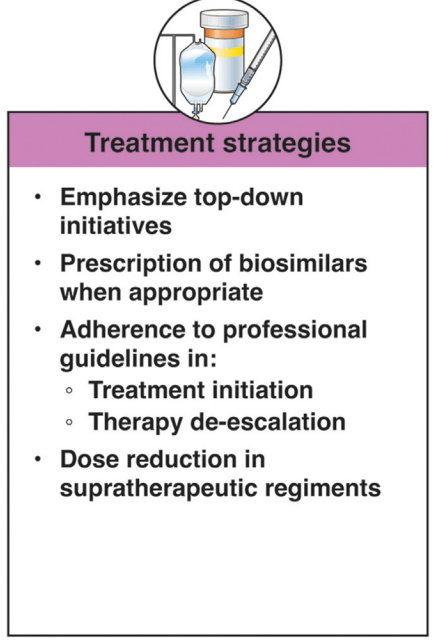

Nevertheless, understanding the approximate prevalence of pediatric IBD in the US allows for adequate human and financial resource planning for this important population of children with an impactful chronic disease. The high prevalence should raise concerns among health care practitioners and policy makers that we have under-resourced IBD care in children, especially considering the high rate of use of biologics and the growing direct health costs incurred in the treatment of this population.11

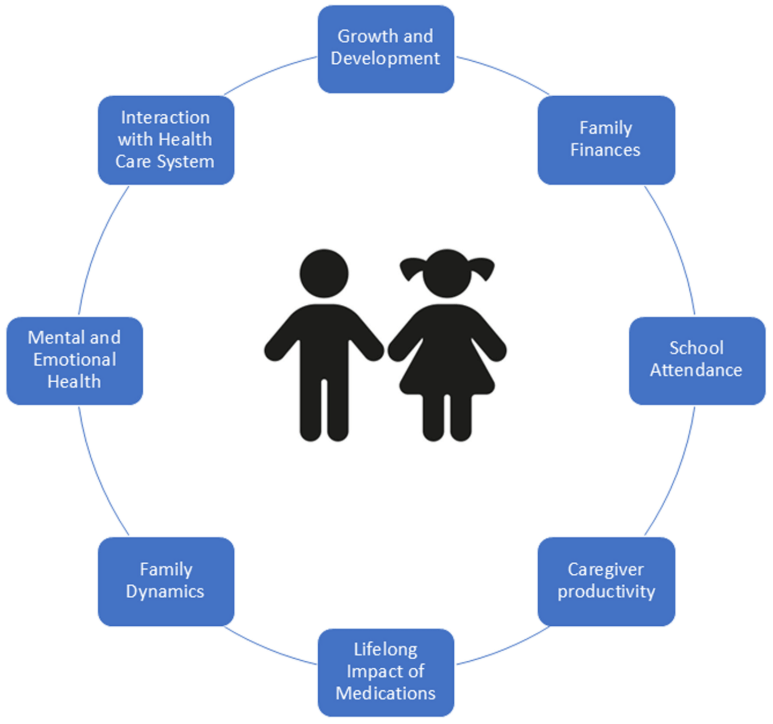

The burden of IBD in pediatrics goes beyond that of the child. Compared with adult IBD, it disproportionately affects caregivers and families (owing to missed work for appointments, hospitalizations, and home care), mental health of both the patient and the parents, and the health system...

They report that pediatric IBD is more frequent among White children and adolescents (145 per 100,000) compared with Black (91 per 100,000) and Hispanic (88 per 100,000) children, whereas children of Asian origin have markedly lower rates (52 per 100,000).“

My take: The updated prevalence data helps understand the increasing frequency of pediatric IBD. The associated commentary reminds us of the broader burden the disease has for families and for our communities.

Related blog posts:

- U.S. IBD Prevalence: 7 in 1000 (2023)

- Predicting the Burden of IBD Until 2040 (2024)

- Trends in Pediatric IBD Epidemiology & More on Formula Recall

- IBD Updates: Rising Burden of IBD, Calprotectin in Severe Colitis, Postoperative Therapeutic Drug Monitoring, Formula Choice for EEN

- NY Times: Crohn’s Disease is On the Rise (4/26/21)

- Ups (mostly) and Downs with IBD Epidemiology

- What’s Changing in IBD Care: Hospitalization Rates and Authorizations

- IBD Updates: SC Vedolizumab, PRODUCE study: Specific Carbohydrate Diet, Racial Epidemiology of IBD, and Microbiome in UC

- Nutrition Week (Day 7) Connecting Epidemiology and Diet in Inflammatory Bowel Disease