M Mouchli et al. Liver Transplantation 2025; 31: 781-792. Long-term (15 y) complications and outcomes after liver transplantation for primary sclerosing cholangitis: Impact of donor and recipient factors

Methods: Using Mayo clinic prospectively maintained transplant database, 293 adult patients (>18 y, mean age 47 yrs) with PSC who underwent LT from 1984-2012 were identified. Patients with cholangiocarcinoma were excluded. One hundred and thirty-four patients received LT before 1995, and 159 were transplanted after 1995.

Key findings:

- The 1-, 5-, 10-, and 15-year cumulative incidence of recurrent PSC was 1.0%, 8.0%, 23.5%, and 34.3%, respectively.

- Vascular and biliary complications are frequent: hepatic artery thrombosis (N = 30), portal vein stenosis/thrombosis (N = 48), biliary leak (N = 47), biliary strictures (N = 87)

- Graft failure occurred in 70 patients

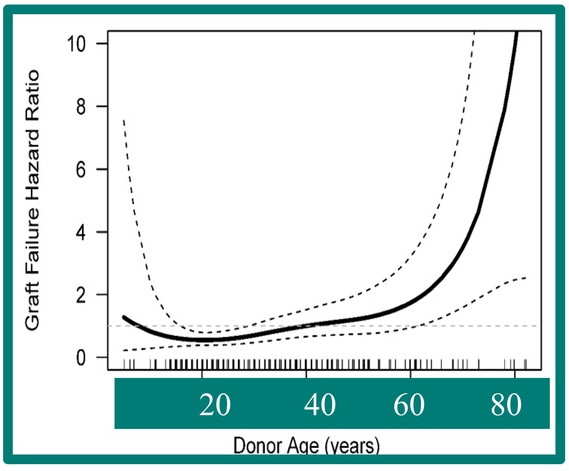

- Donor age >60 years was associated with an increased risk of recurrent PSC.

My take: Overall, there was a good survival rate despite the increased frequency of vascular and biliary complications. Also, 2/3rds of patients did NOT have recurrent PSC. Older donor age was associated with higher graft failure in this cohort.

Related blog posts:

- Recurrent PSC in Children After Liver Transplantation

- Cholangiocarcinoma Risk in Pediatric PSC-IBD Plus one

- ESPGHAN Guidelines for PSC in Children

- Aspen Webinar 2021 Part 5 -Autoimmune Liver Disease & PSC

- Easy Advice for Pediatric Hepatologists: PSC Surveillance Recommendations

- Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis (PSC) –Natural History Study

- AASLD 2023 Practice Guidance for Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis and Cholangiocarcinoma